The origins of the lift pump, like those of many other indispensable inventions, are lost somewhere in the distant past.

The principle behind the pump’s operation — atmospheric pressure — was not discovered until the 17th century. But by then lift pumps had already been in use for generations. For miners and seamen, especially, they had long been an essential part of everyday life.

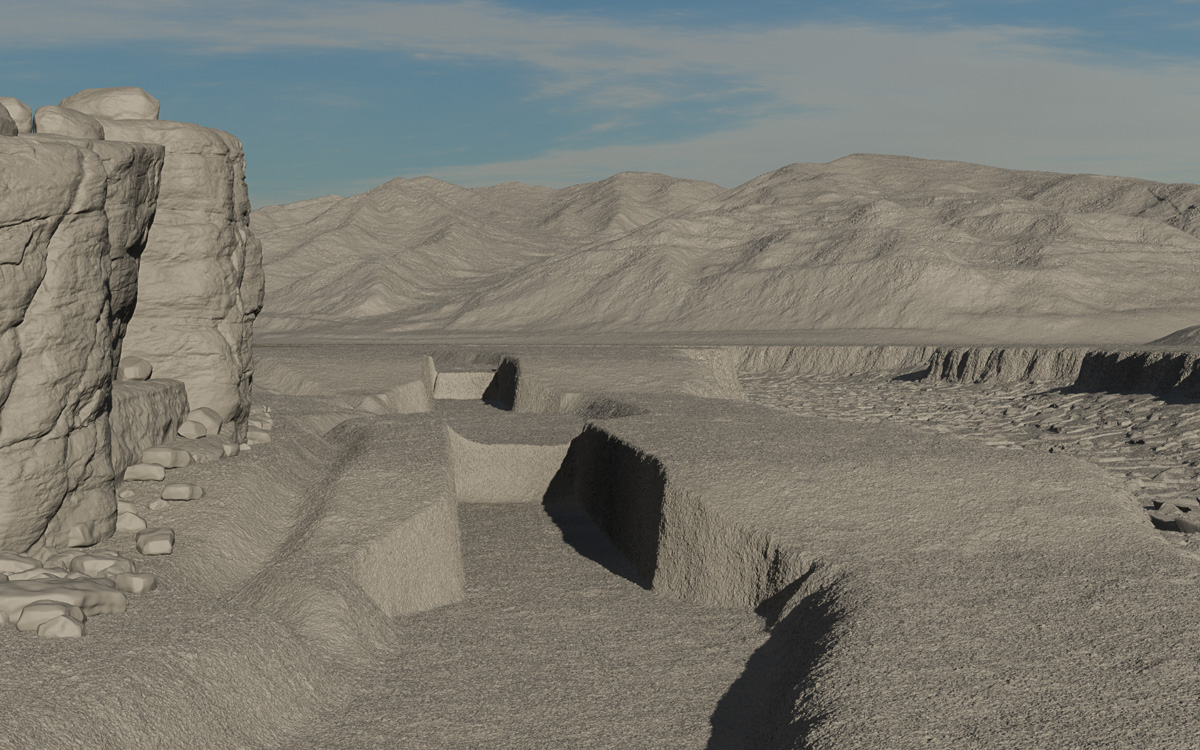

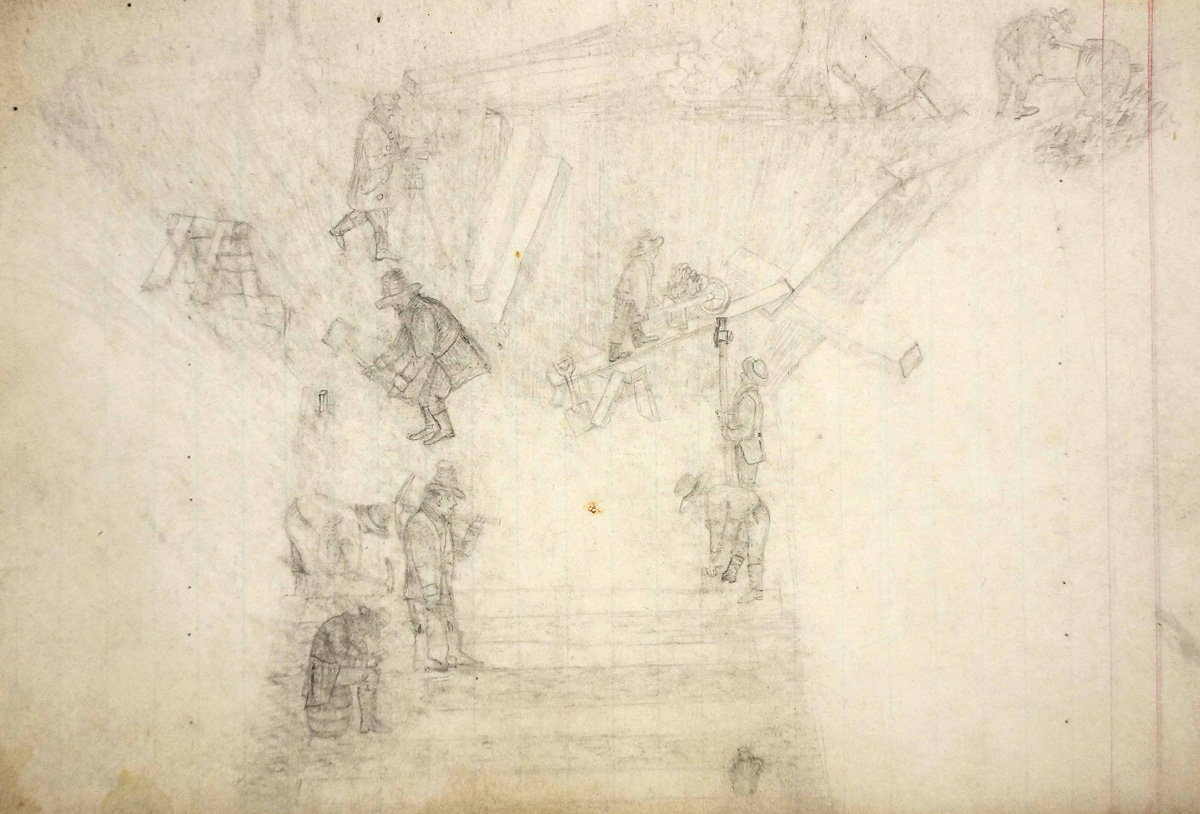

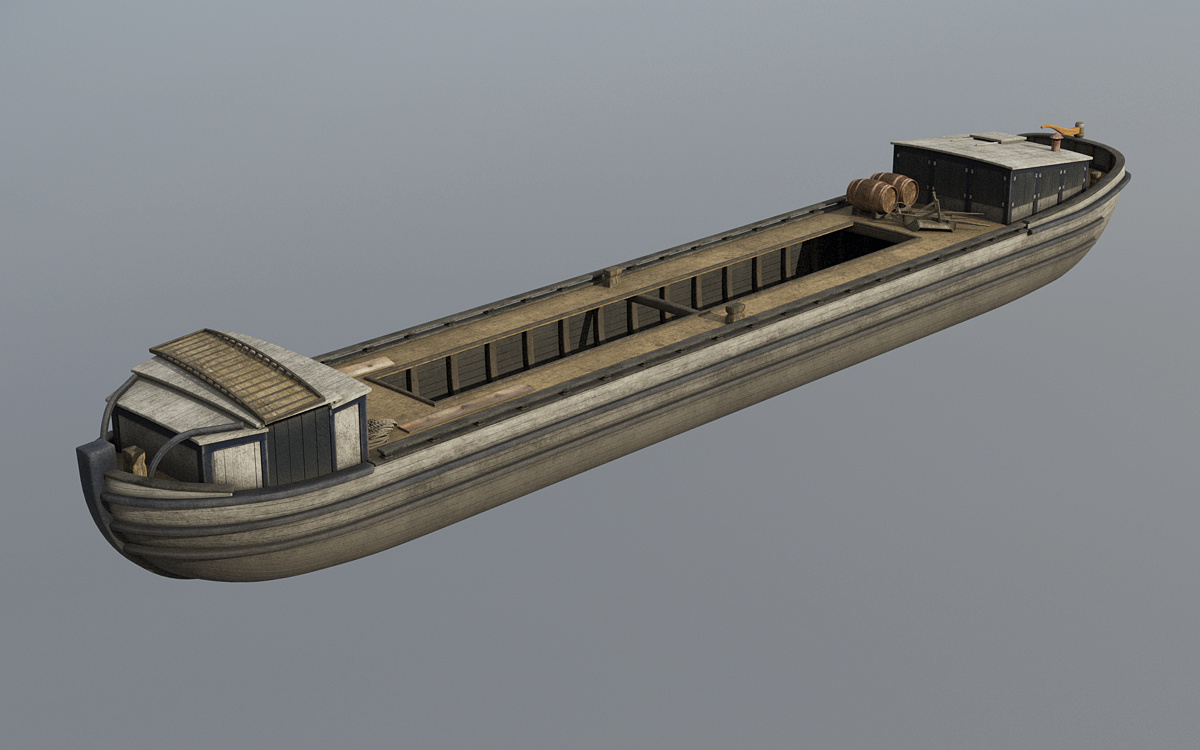

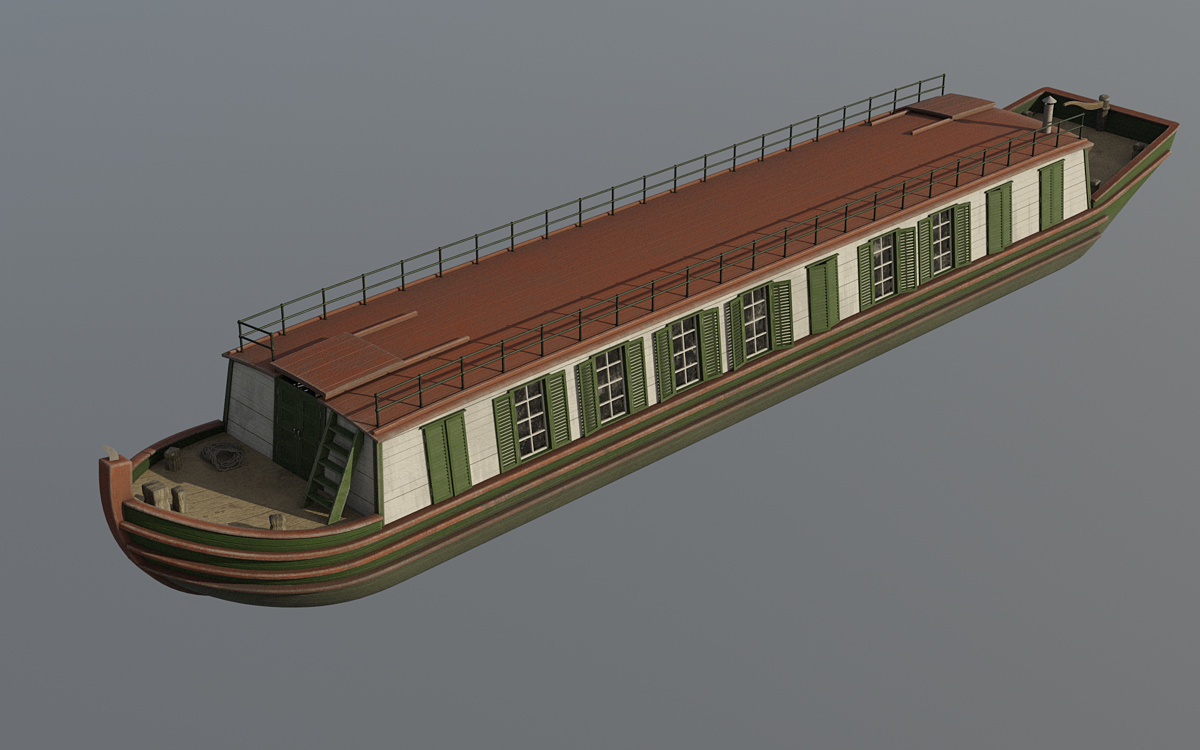

Some time ago I began working on a scene to show workers digging the Erie Canal through Cayuga Marsh. The scene needed to include the hand-powered pumps they used to get rid of the water that constantly seeped into the excavation. I made some preliminary inquiries and could not find a source that could tell me what those pumps looked like. (Maybe no one knows.) So I decided to dig deeper.

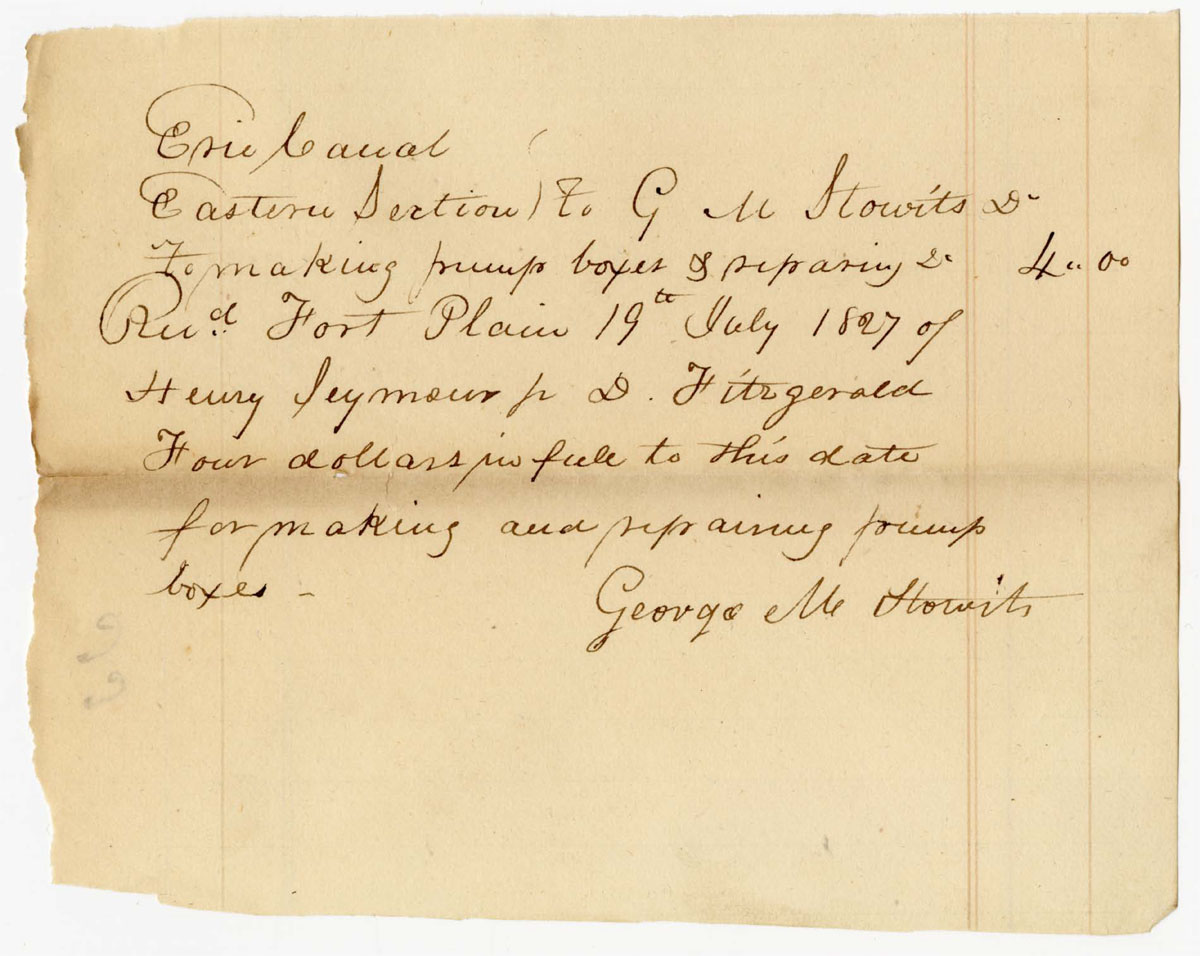

In part one, we combed through contractor receipts for clues. This part will show what I’ve learned from the broader technical record, as presented in contemporary documents.

In its most basic form, the lift pump (also called the piston pump, atmospheric pump, or suction pump) has just a few parts.

The body is called the box. It can be a cylinder or, literally, a box. The lower end is open (though it may be protected by a screen or cage) and extends below the water surface. Inside the box, a piston (a.k.a. the sucker or bucket), is attached to a rod (or spear) and handle (or brake). There are two valves, one at the bottom of the box near the intake, and another in the piston.

When the handle is pushed down, the piston valve opens to allow the water in the box to flow up past it. When the handle is pulled up, that valve closes, lifting the water above the piston, and the intake valve opens to admit more water into the box.

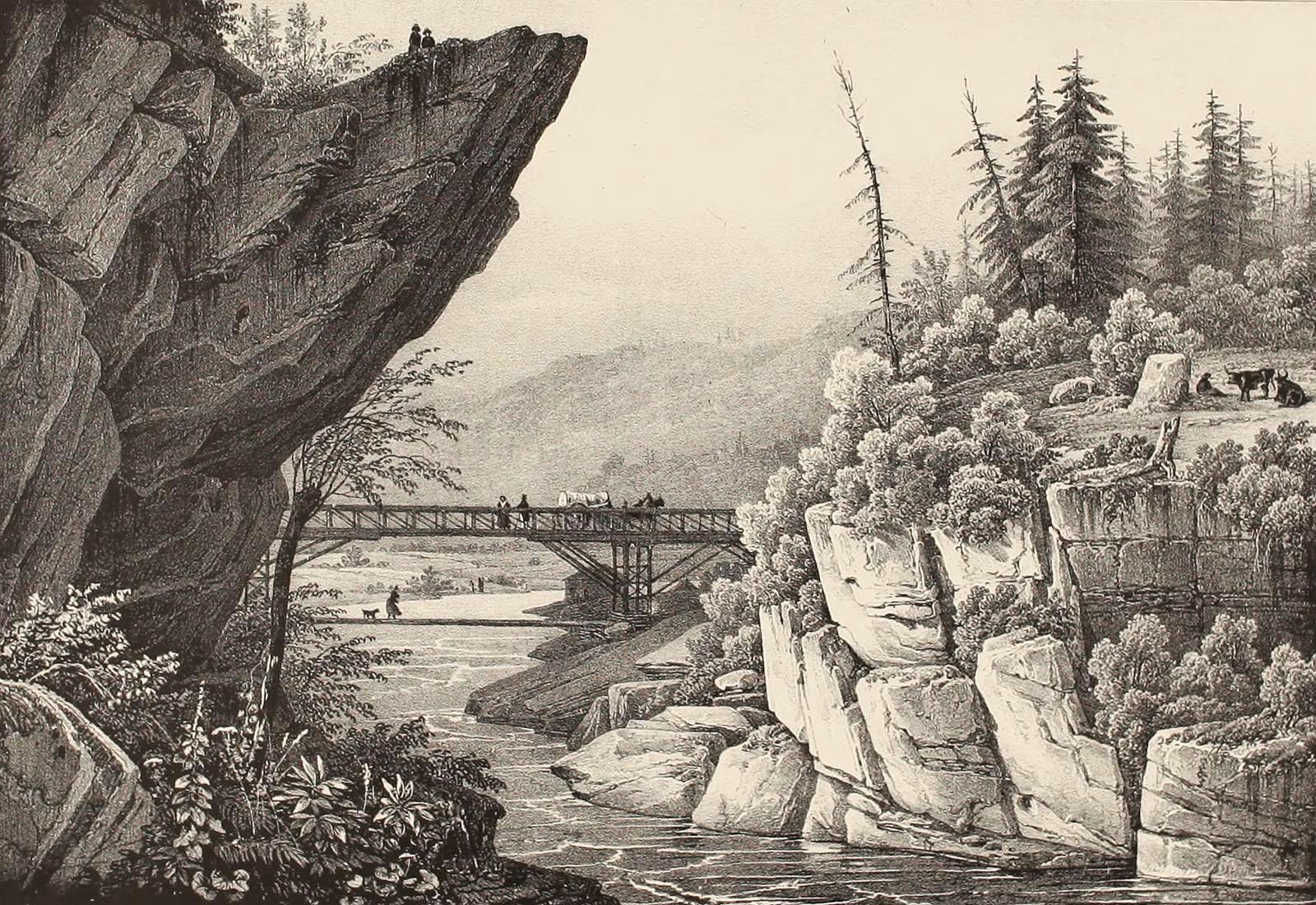

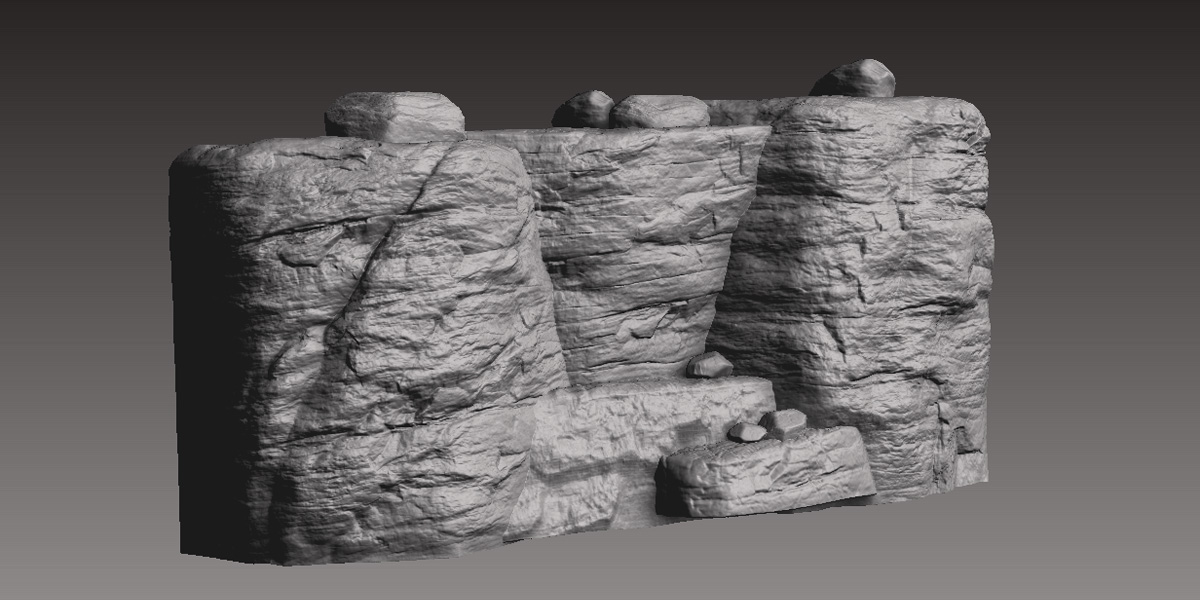

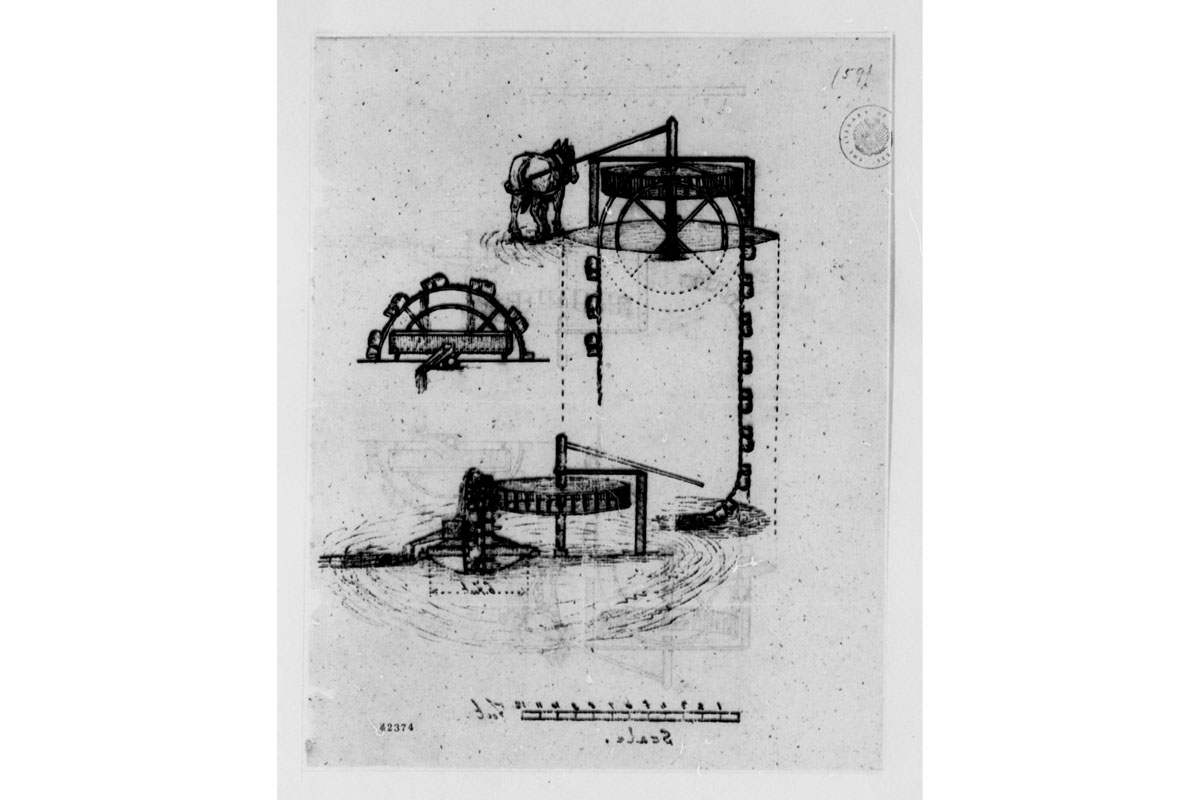

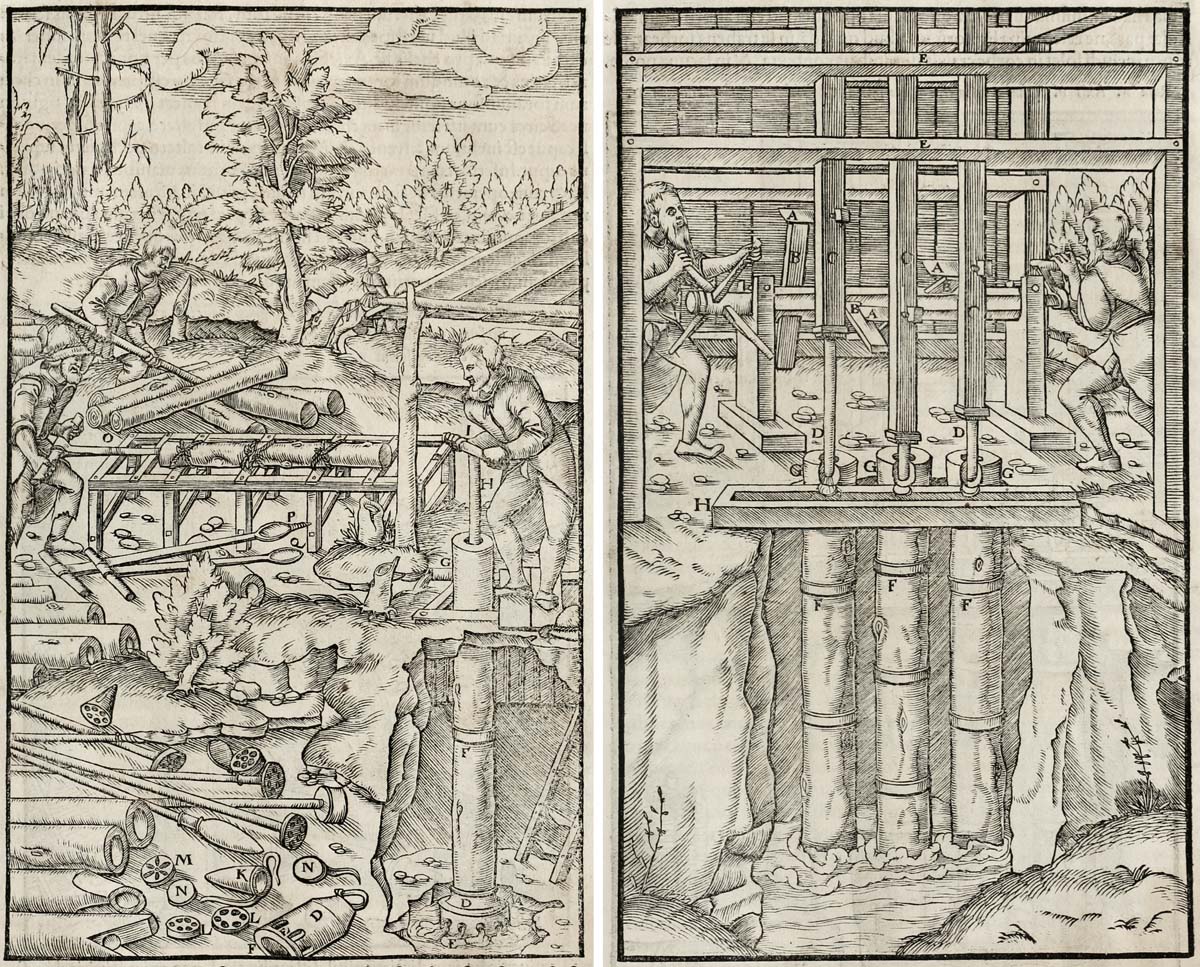

An extraordinary set of woodcuts published in Georgius Agricola’s 1556 treatise De Re Metallica (On the Nature of Metals) show a series of lift pumps of increasing complexity, some powered by hand, others by water wheels, all used to drain mines. In one (shown in the image to the left at the top of this post), a laborer operates a wooden pump while another cores logs for pump boxes and pipes. Scattered in the foreground are spears, pistons, grates, and all the other parts needed to build the pump.

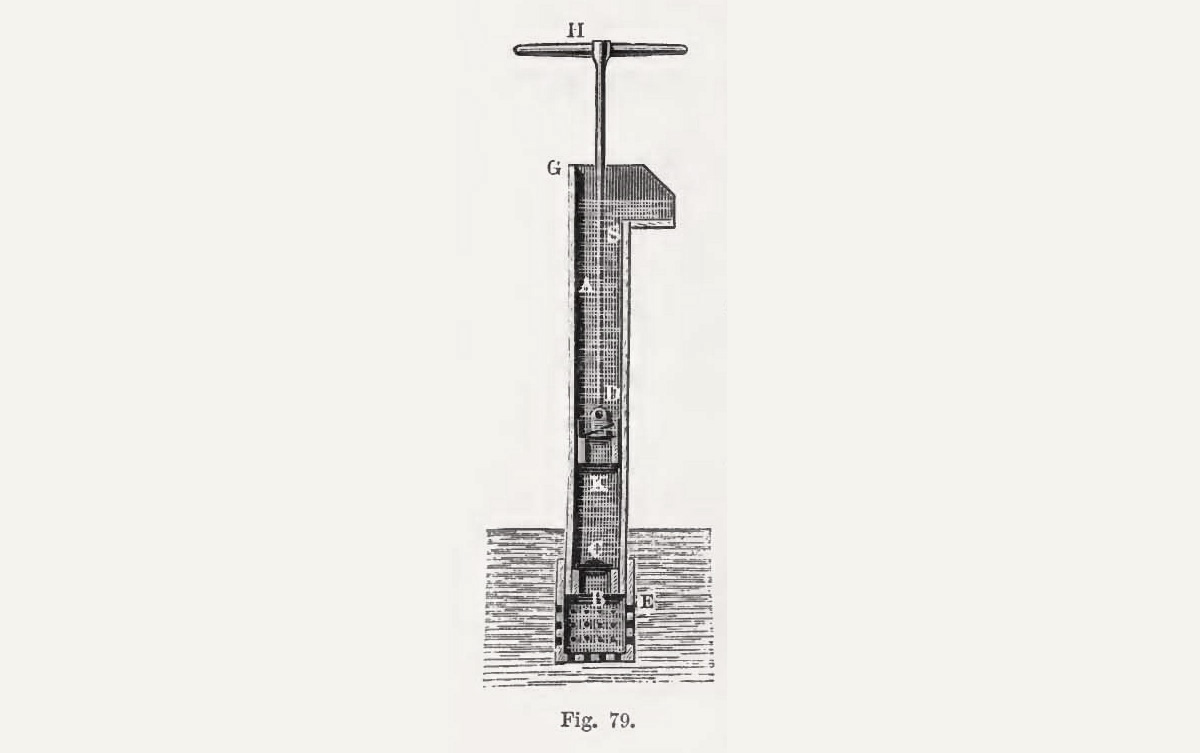

Agricola’s pumps are functionally equivalent to the simple machine shown in the second image, above. That diagram was published in 1897, more than three centuries later. The hand-operated pump it depicts was used to drain excavations. Not much had changed.

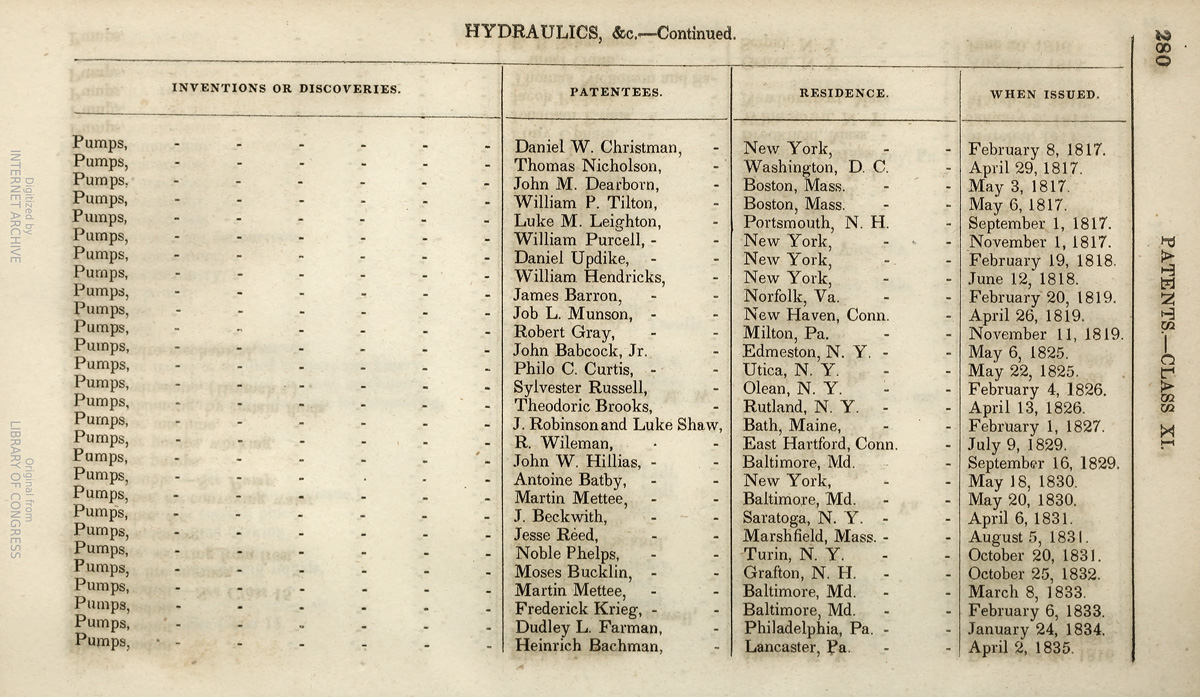

It wasn’t for want of trying. More than a hundred patents for pumps were granted during the early 19th century. Some were featured in technical publications such as The Franklin Journal and American Mechanic’s Magazine, which may have summarized their collective significance in this review, published in 1836: “there is not in the description any thing that regards construction or arrangement which is worthy of particular notice, or that is in any respect superior to the pumps now in use.”

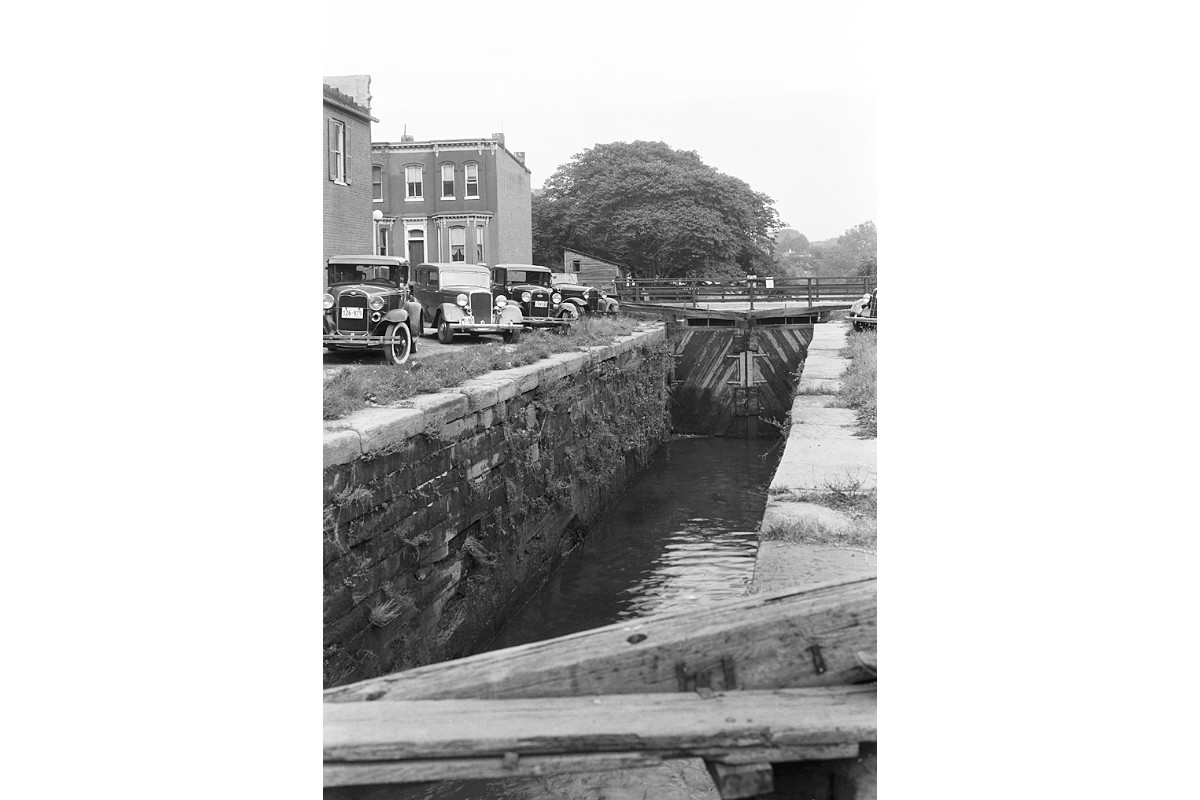

The diggers excavating the Erie Canal would have to solve the vexing problem of excess water by using simple machines built as they had been built for centuries — from wood, wrought iron, and leather.

The virtue of simplicity

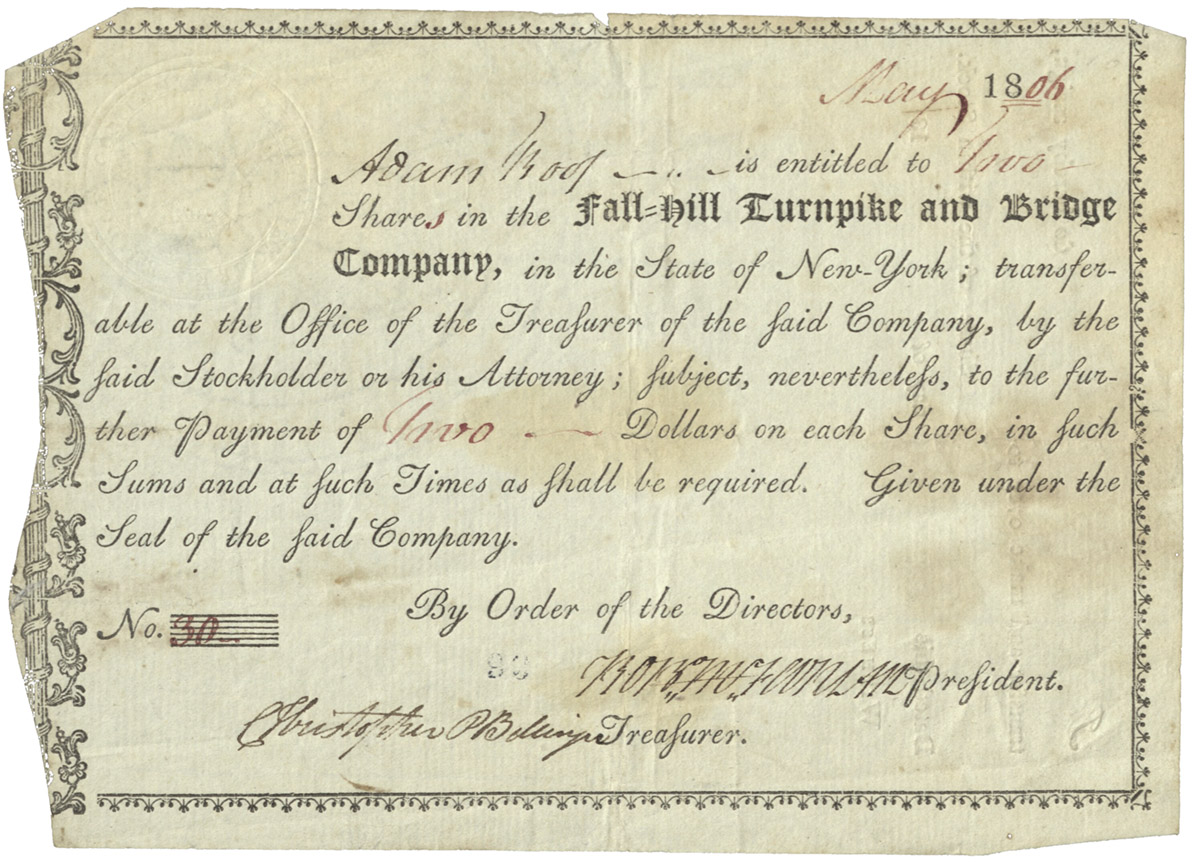

There is little doubt that most of the pumps used along the Erie Canal were made of wood. The raw material was readily available, and there is good evidence that the machines were made and repaired by local craftsmen.

As Thomas Ewbank wrote in his 1849 opus, A Descriptive and Historical Account of Hydraulic and Other Machines for Raising Water, Ancient and Modern: “The facility with which wooden pumps are made and repaired, the cheapness of their material, the little amount of friction from pistons working within them, and their general durability, have always rendered them more popular than others.”

Ewbank, an English immigrant who briefly served as commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office, also described a simple piston used by pump builders in upstate New York. It was a “hollow cone or truncated cone of strong leather, the base being equal in diameter to that of the pump chamber or cylinder . . . When thrust down it collapses and permits the water to pass between it and the sides of the chamber, and when its motion is reversed, the weight of the liquid column above it, presses it out again.”

Picture an inverted parasol that closes and opens as the pump handle is lowered and raised.

The design, Ewbank wrote, “has long been known in some parts of the United States. We noticed it twenty years ago [that is, during the late 1820s] at New Rochelle, Westchester County, in [New York] and were informed by a pump maker here that they ‘always had it.’ It is not however universally known, for in 1831 a patent was taken out for it.”

That patent was awarded to Noble Phelps, of Turin, New York, on October 20, 1831. A review published in the Journal of the Franklin Institute noted that the improvement was a piston or “leather bucket in the form of the letter V . . .”

Other accounts emphasized the advantages of simple machines made from everyday materials.

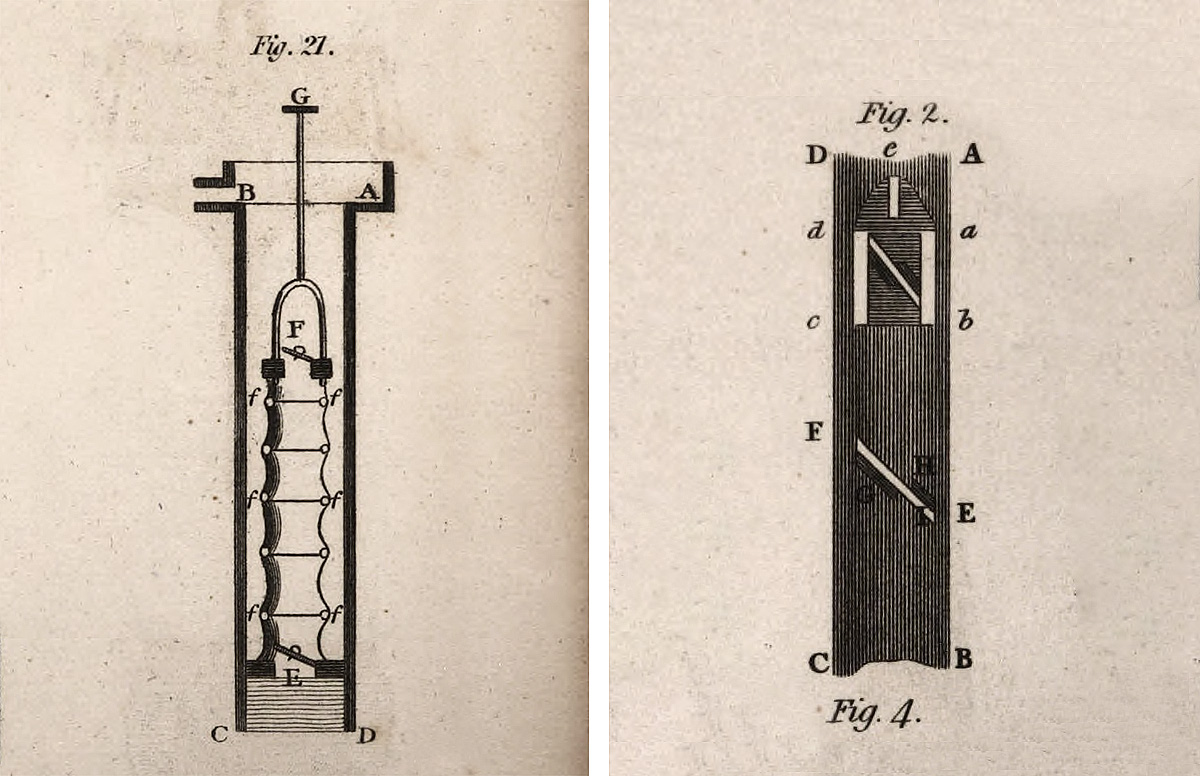

In 1815 Englishman Olinthus Gregory in A Treatise of Mechanics — Theoretical, Practical, and Descriptive described a pump that could be built by “a common carpenter.” The design (above, at left) used a cylindrical bellows made of leather or canvas instead of a piston. The main advantage was that a precise fit between the bellows and pump box was not required, so the box could be cylindrical or square. The lack of friction reduced wear and (in theory, at least) extended the useful life of the machine.

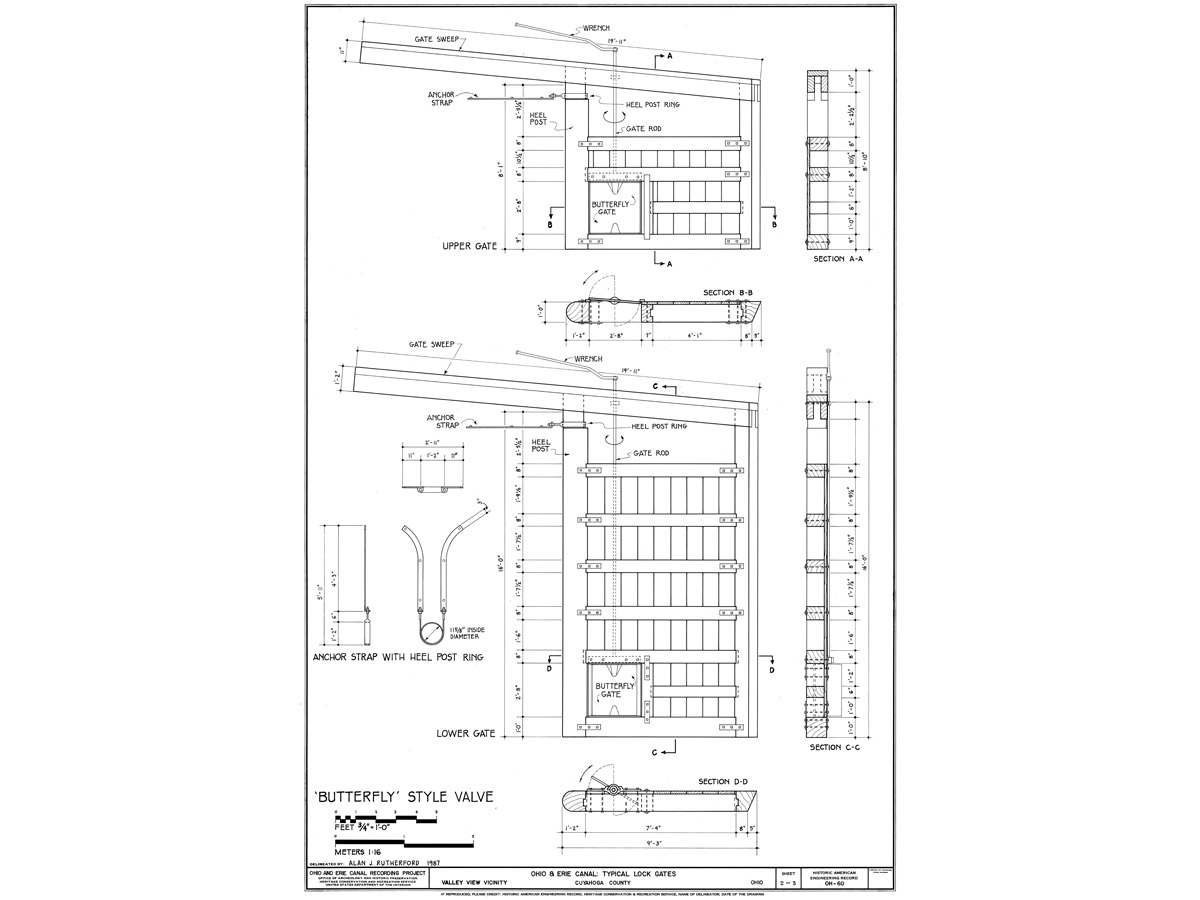

Gregory also described simple butterfly valves (above, right), fabricated from wood and leather, that would fit inside a square pump box.

Elsewhere, he goes into some detail how wood pistons should be lined with leather to create watertight seals with minimal friction — a passage that sheds some light on items found in Erie Canal contractor receipts (such as this one from January 13, 1819: “for Leather to Leather the Boxes for two pumps”).

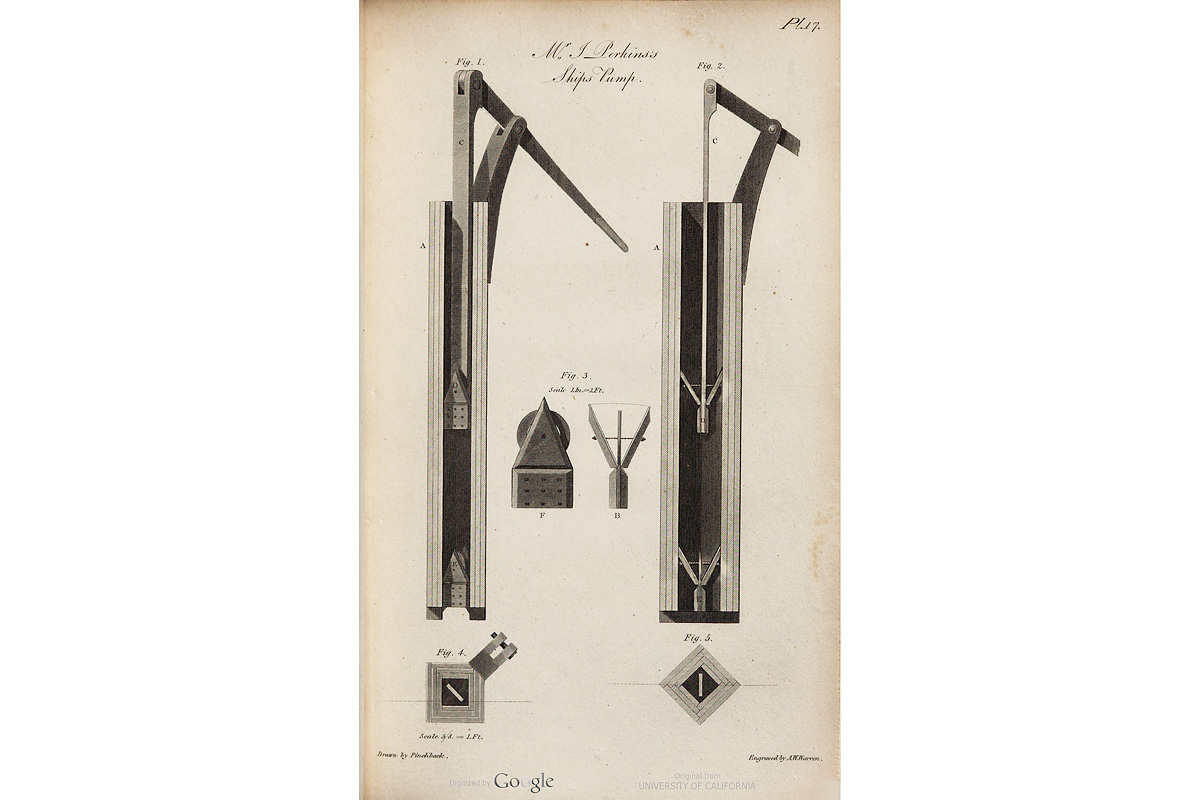

The London Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce in 1820 awarded a “large gold medal” to Jacob Perkins for devising a ship’s pump built of planks. “The object of the peculiar modification of this pump,” notes the Society’s Transactions, “is that of enabling sea-faring people to construct a pump while at sea from materials always to be found on board; viz. deal boards or planks, leather, nails, canvas, and tar.”

The plank construction eliminated the “necessity of boring the barrel, as in the usual pumps.”

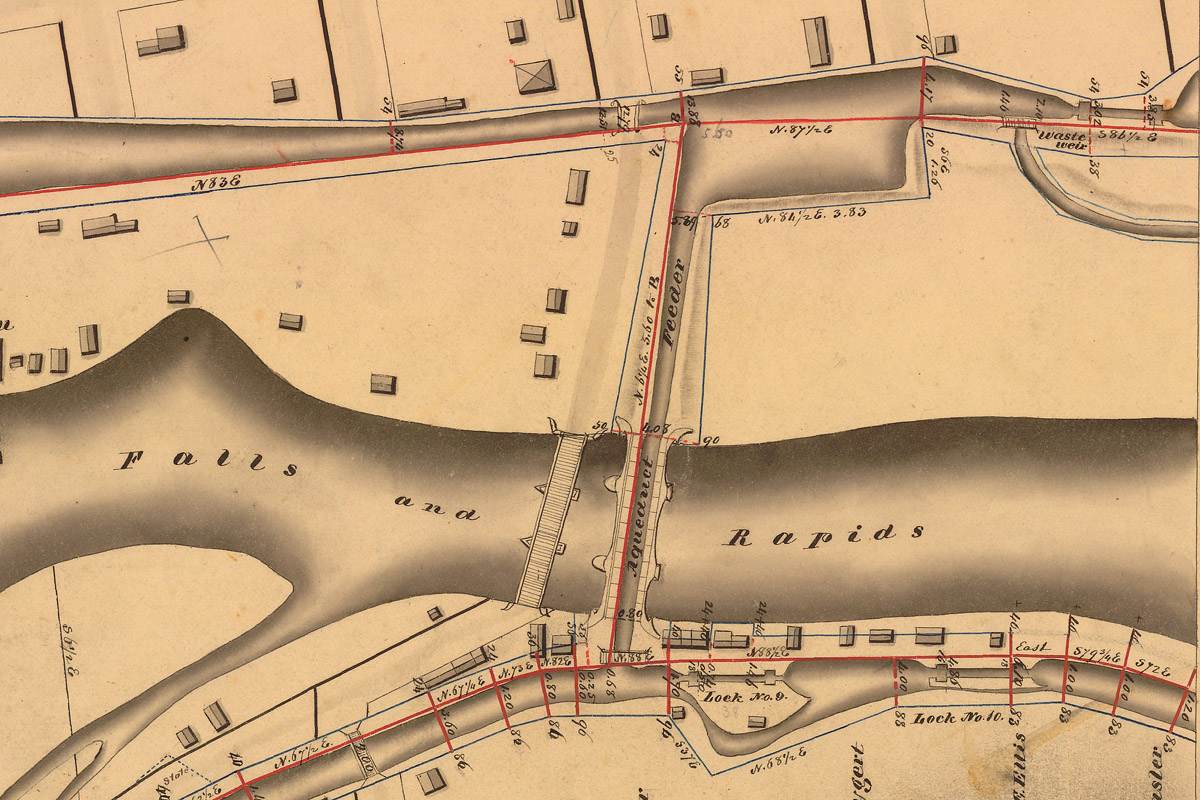

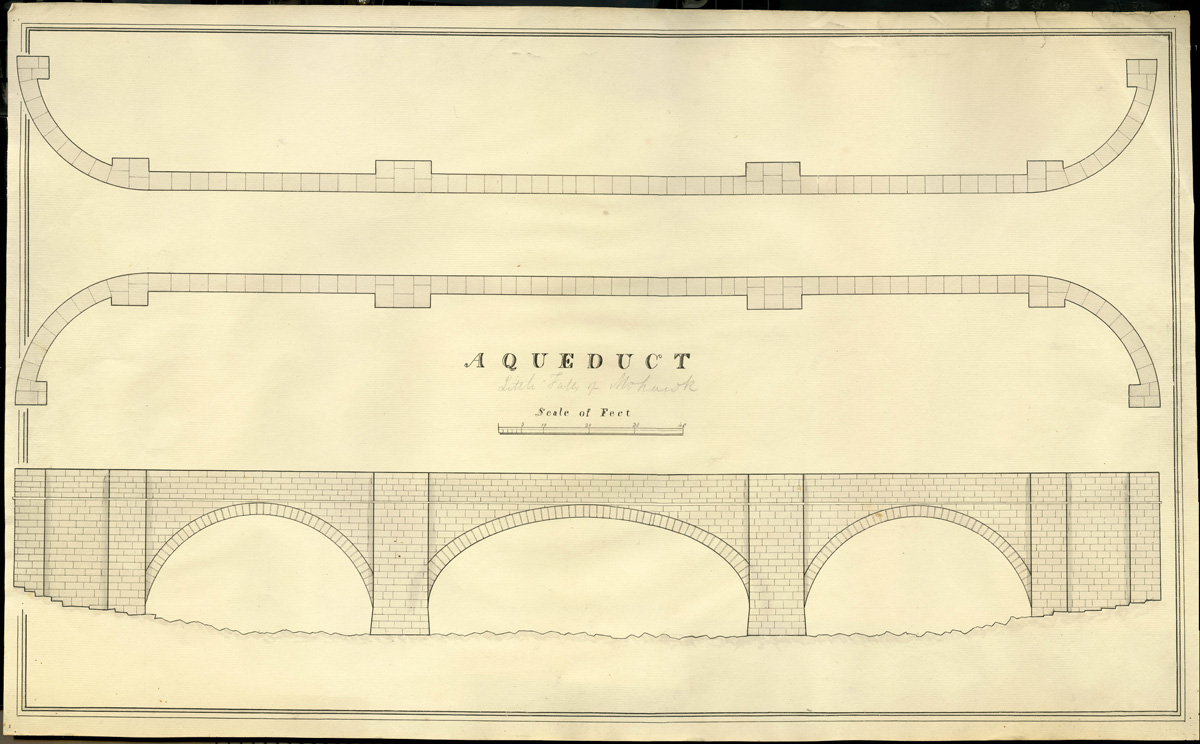

Cored logs, of course, had been used as pumps since ancient times, as shown in Agricola’s woodcut. They also were used as water pipes, and references to them can be found in Erie Canal contractor receipts. (For example, in 1823 John M. Smith was paid $50.79 for, among other things, “5 Rods of new pump logs laid under Canal.”)

Two are better than one

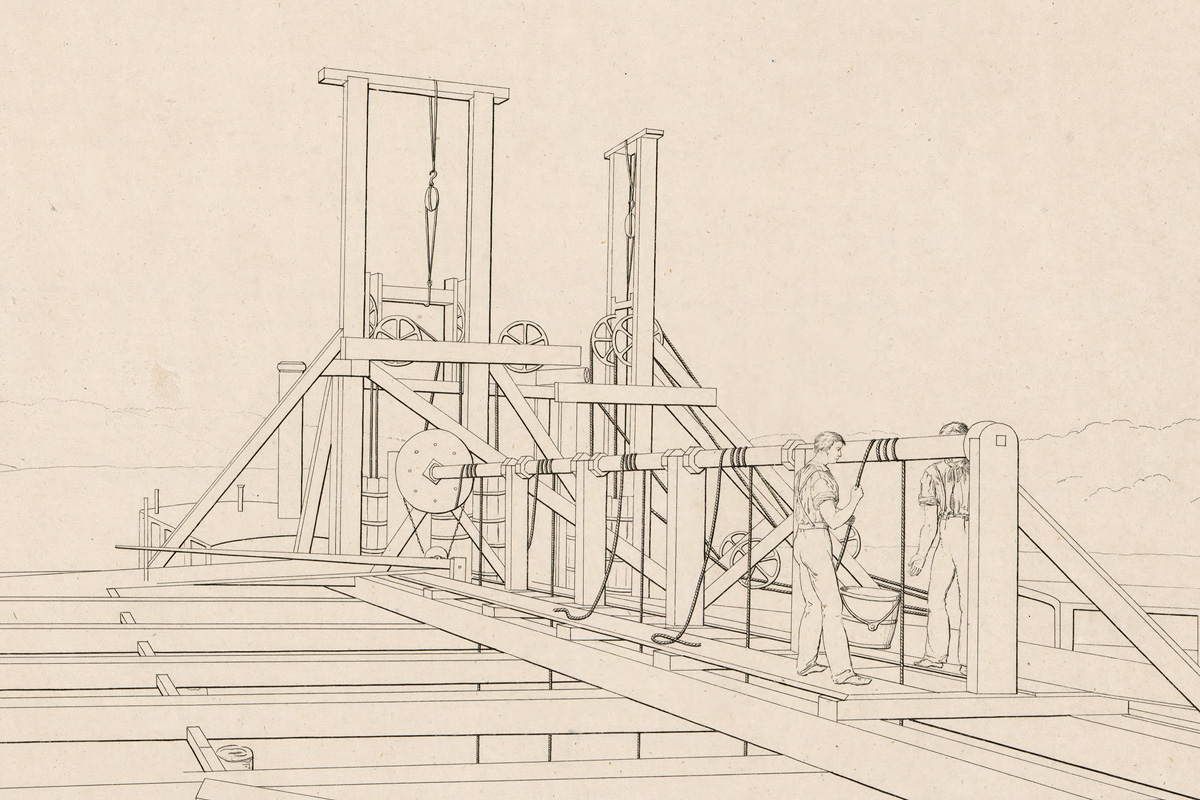

Over the centuries, builders experimented with various combinations of pumps. Several woodcuts in Agricola’s book show machines made up of two, three or even more pump boxes, arranged side-by-side (see the first image at right, above) or one above the other, like a staircase.

The simplest arrangement combined two pumps with a single lever operated by two men. Bilge pumps on the 74-gun battleship U.S.S. North Carolina, launched in 1820, worked this way, according to Ewbank: “The levers are double, and shaped like those of fire-engines, staves of wood being slipped through the rings whenever the pumps are worked.”

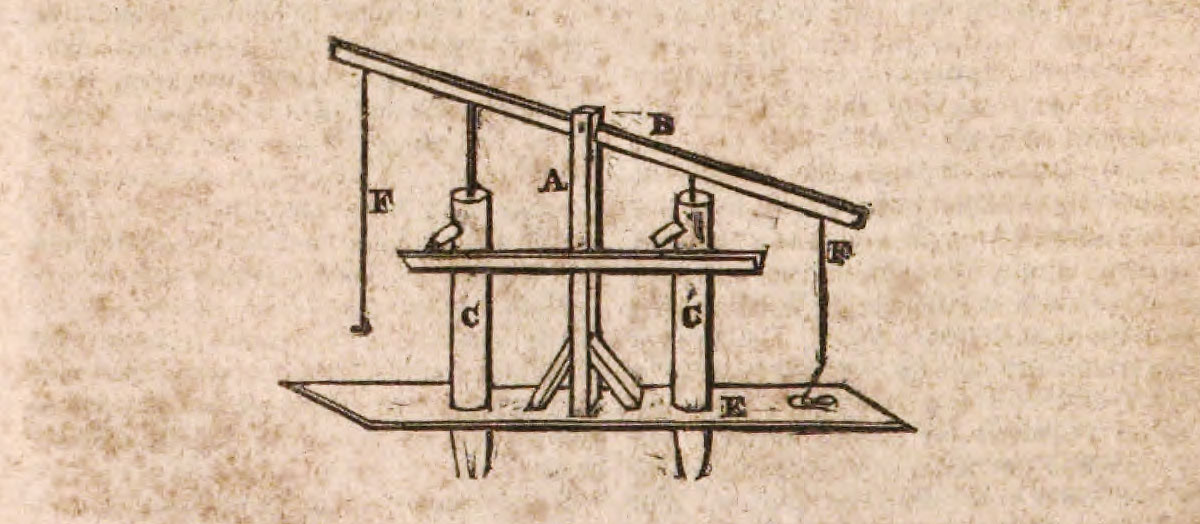

In a letter to American Mechanic’s Magazine, May 21, 1825, a P. Vanryde mentions a double pump that he had “frequently seen working in Holland.” He helpfully included a sketch: “Thus two men can raise an immense quantity of water in a day, as there is a constant stream from one or the other.” The scale of Vanryde’s drawing is not shown, but similar illustrations indicate that the pump barrels were taller than man-height. The lever is operated by pulling on the ropes at either end.

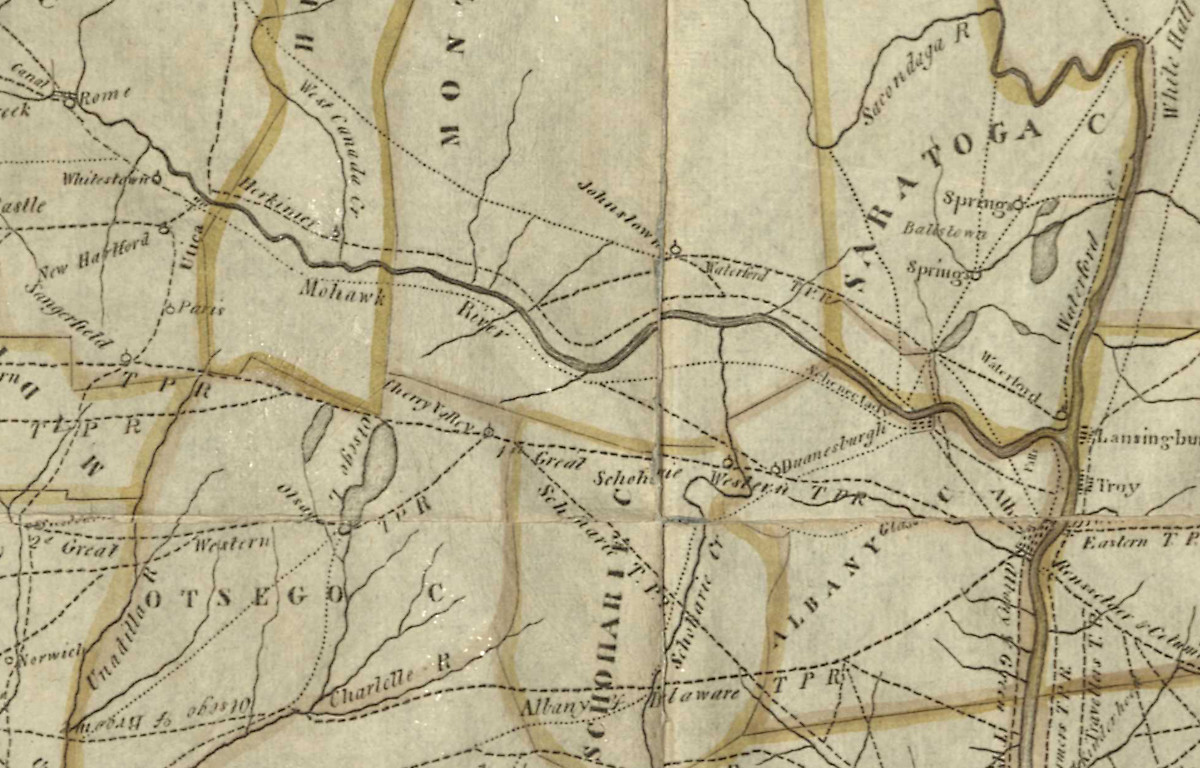

(This may be a good place to insert a reminder that the first European settlers of the Hudson and lower Mohawk valleys were the Dutch, masters of hydraulic engineering who would have brought this technology with them.)

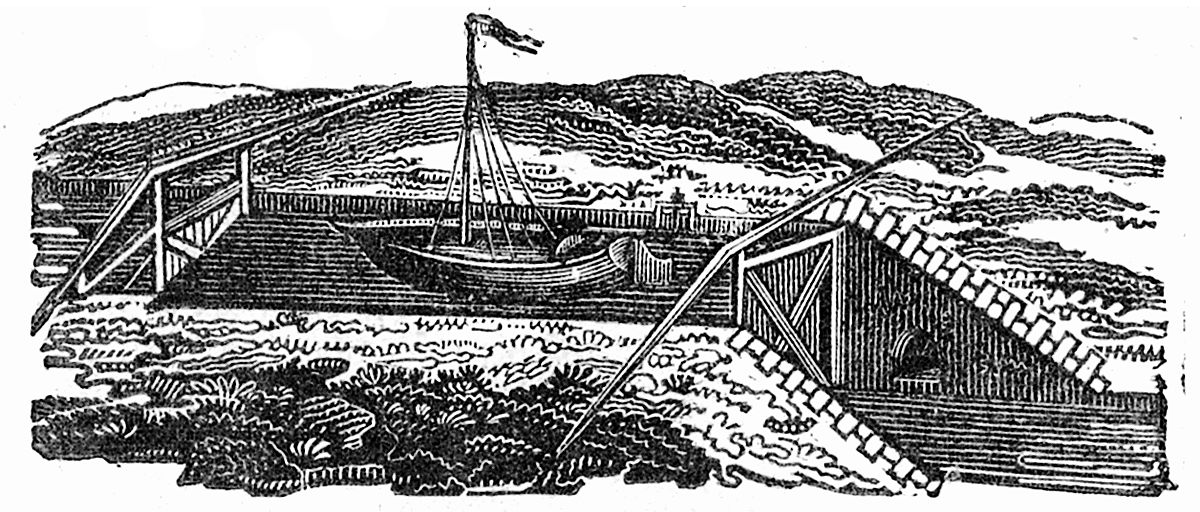

One of the most intriguing examples dates from more than 60 years earlier. In Whole Art of Husbandry; Or, the Way of Managing and Improving of Land, published in 1761, Englishman John Mortimer teaches readers how to mine marl deposits (marl, a mixture of clay and calcium carbonate, was widely used as a soil conditioner) and what to do when the pit became flooded with spring water.

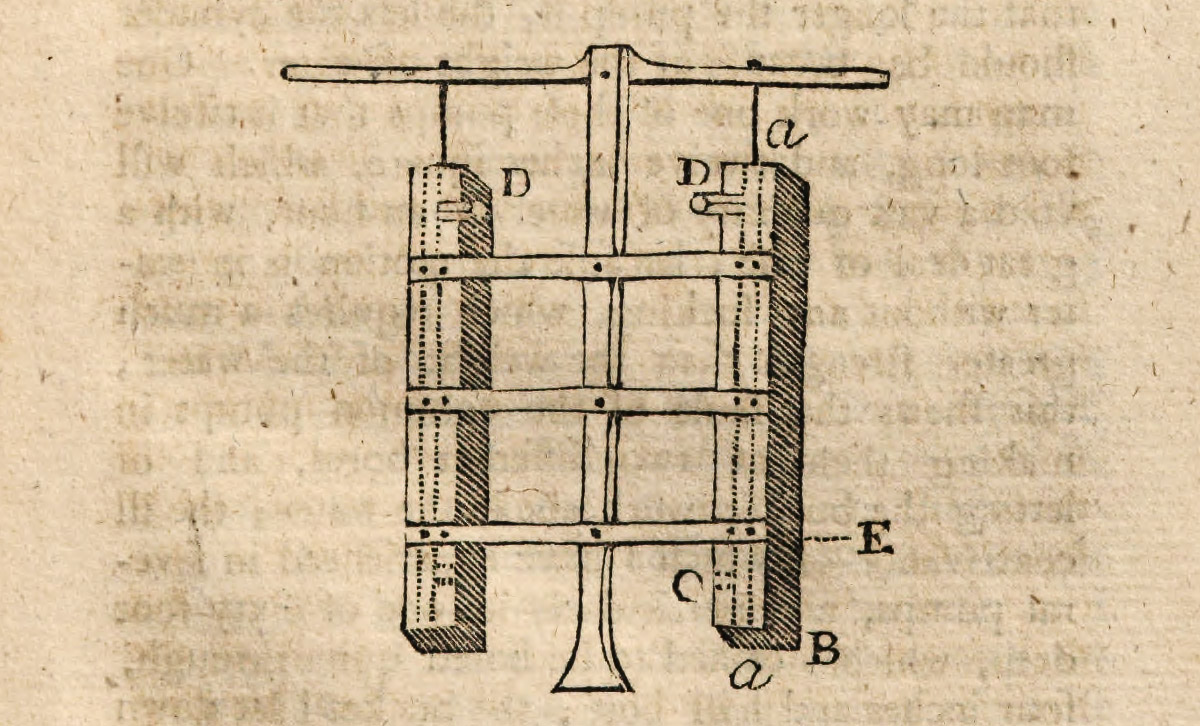

“I shall propose one of the cheapest and best pumps that is for their use; which is to take four deals or other boards, which joint and nail together; and if some plates of iron be nailed over the edges of them, it will strengthen them much; these pumps may be made single, with a common pump-handle to them for one man to work them, or double for two men, as in the figure . . . One man may work one of these pumps that is twelve foot long, and twelve inches square, which will void a vast quantity of water in an hour, with a great deal of ease.”

Later authors copied Mortimer’s design, which may be evidence of its popularity — and also evidence that it worked.

Could this, or something similar, have been used on the Erie Canal?

The marl reference is an interesting coincidence. The crumbly, stony material was encountered by contractors in several locations along the canal line, where it was notoriously difficult to excavate.

But Mortimer’s pump also satisfies all the requirements for the kind of machine we’d expect to find on the New York frontier from 1817 through 1825: The simple plank design could have been built by any local carpenter or millwright, the finished pump could have been operated by one or two men, and (most important) it could “void a vast quantity of water . . . with ease.”

Something tells me we’re getting close.

If you or someone you know is familiar with 1820s construction technology, I’d appreciate hearing from you. Please leave a comment here or contact me via email at smb (at) steveboerner (dot) com. Thanks!