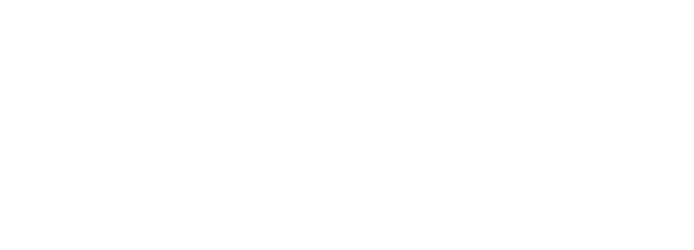

Work on the Cayuga Marsh scene had been going really well. The basic terrain was in place and ready for the next step – adding models of the workers and the machines they would have used.

But a brief passage in a primary source suddenly brought everything to a halt. It occurs in an 1824 legislative committee report on a financial scandal that was ending the career of Myron Holley, treasurer of the canal commission.

Alfred Hovey and Abel Wethy, the contractors responsible for the Cayuga Marsh canal section and the Rochester aqueduct, appeared to have been overcompensated by Holley for their work. Suspecting collusion, the committee scrutinized their accounts and visited both locations. The contractors were cleared of wrongdoing, but in its report the committee documented the difficulties they had encountered while constructing the canal through the marsh, where the excavation was often under water.

The report reads: “The great difficulties which had to be encountered in the prosecution of this work, was a subject of deep anxiety to the [canal] commissioners, as this section was a connecting link between finished portions of the canal on each side of it. . . . Hovey & Wethey went on with the work in the winter of 1822, and prosecuted it with great energy. In the prosecution of this work, both summer and winter, the contractors were compelled to keep pumps in operation, night and day, to enable them to go on with the work.”

That last sentence was the show stopper. I had no idea what kind of machines they were talking about.

The handful of other pump references in the canal commissioners’ reports are not helpful. Nowhere do they offer even the briefest description. Why should they? This was pedestrian technology. At the time, everyone knew what an early 19th-century excavation pump looked like and how it worked.

Until we didn’t. As with many other details of early Erie Canal history – especially those concerning the daily lives of working people – much of what we once knew about these poorly documented machines has, apparently, been lost.

What did the machines look like? What were they made of? How were they powered? By hand? Horse? Steam?

It’s an historical puzzle, and until it’s solved the Cayuga scene will have to be put on the shelf. That’s okay – there are plenty of other projects to work on.

Beyond that immediate concern, though, is something larger. The better we understand the technology of the day and the tools that were used, the more we will understand the day-to-day experience of the workers who built the canal.

Could the pumps have been steam-powered?

Let’s deal with this question right away.

The steam engine was undergoing rapid development in the early 19th century. The patent on James Watts’ steam engine expired in 1800, allowing competitors to borrow and improve upon his design. In the United States, Robert Fulton built the first commercially successful steamboat and began regular passenger service on the Hudson River in 1807. The Stourbridge Lion, imported from England, would become the first railroad locomotive in the United States in 1829.

In Triumph at the Falls: The Louisville and Portland Canal (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2007), authors Leland R. Johnson and Charles E. Parrish place the first use of steam power for canal construction in late 1827, when contractors on Kentucky’s Louisville and Portland Canal installed a steam pump to drain lock pit excavations.

A few years later, immense steam engines would drive pumps and machinery for construction of the Potomac Aqueduct in Washington, D.C.

But of course, that all came later. For the workers stuck in the middle of a marsh on the New York frontier in 1822, steam-powered pumps would remain at best a distant dream.

Following the money

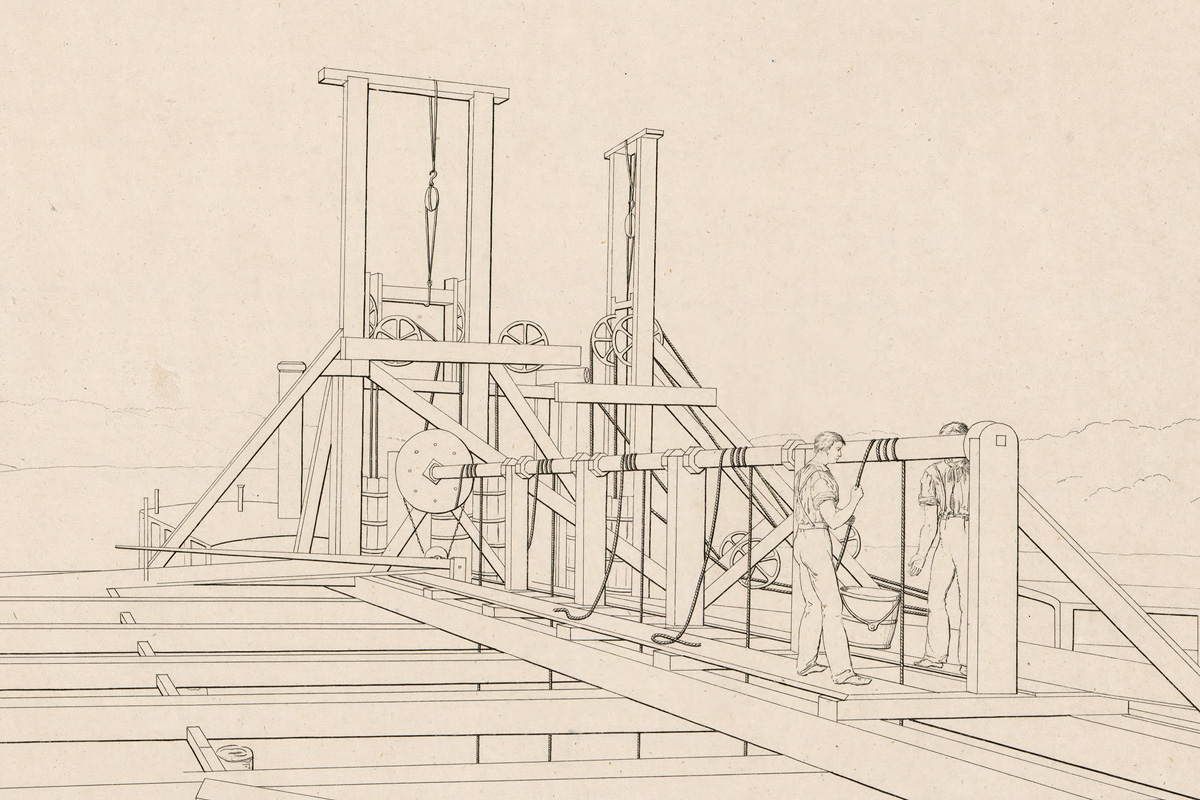

Excess water bedeviled contractors and workers not only at Cayuga, but all along the canal line. Pumps – making and repairing them, using and transporting them – are frequently mentioned in receipts issued to contractors and subcontractors.

Engineer Marshall Lewis, who perhaps brought more practical experience to the field than any of his peers, having previously designed and built locks in Waterloo for the Seneca Lock Navigation Company, also built locks and aqueduct foundations for the Erie Canal. Perhaps because of the nature of this work, Lewis spent a lot of money on pumps.

For example one of his receipts, from December 1818, records a payment of $12.63 to Alvin Upham of Elbridge “for two Large pumps.” ($12.63 in 1818 would be roughly equivalent to $216 today.) Another, to Nathan Young of Jordan dated January 1819, lists an expense of $2 “for two hands to pump one Night.”

Removing unwanted water from excavations was always labor intensive, and the expense could be considerable.

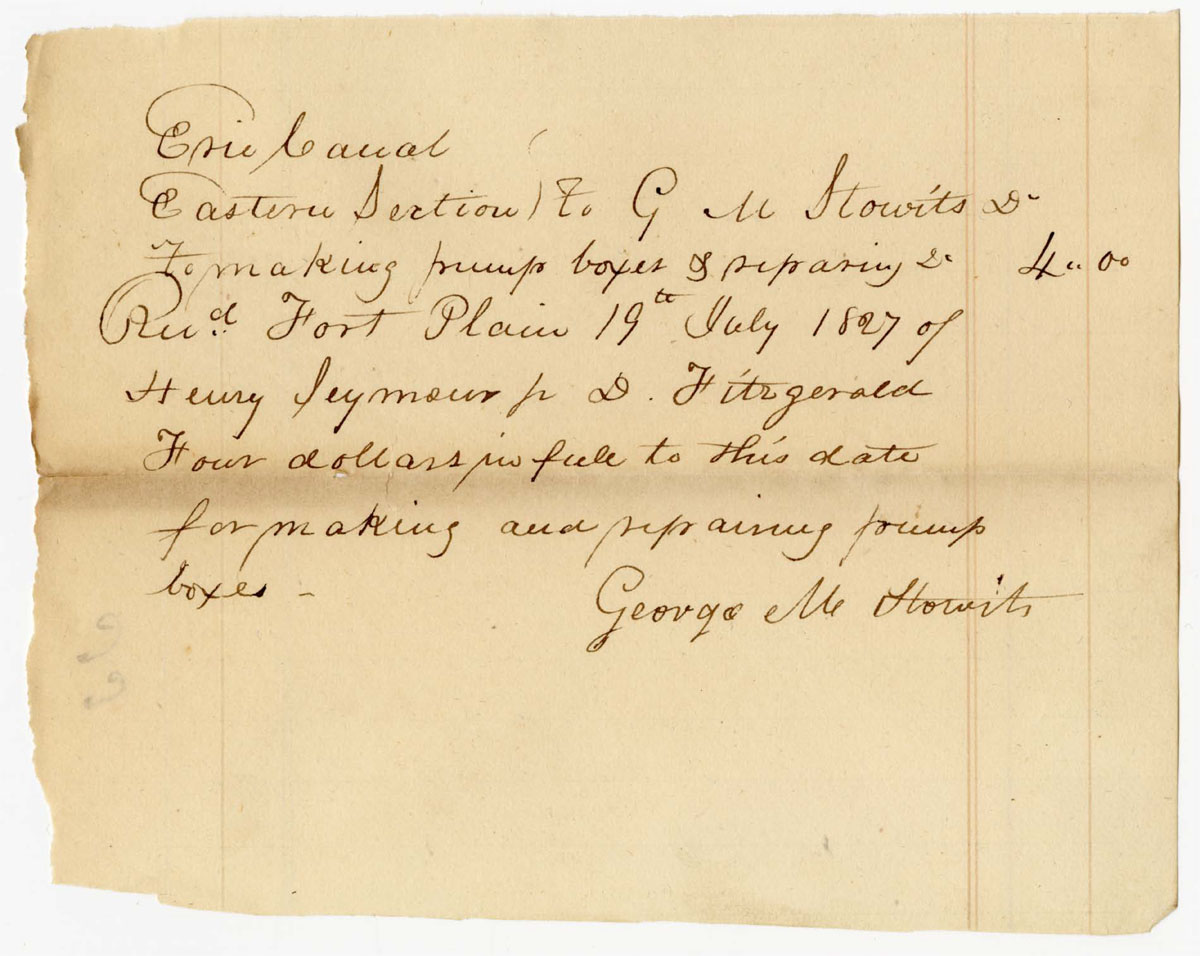

The worst example might be the lower end of the Deep Cut near its junction with Tonawanda Creek, where work was constantly hampered by flooding. “Pumps, worked by horse power, were introduced on almost every section,” reported the canal commissioners in 1825.

This is confirmed by a December 1825 receipt from Principal Engineer Nathan Roberts to contractors Lane and Snyder that included “the expense of several horse pumps and of 163 days pumping estimated at $15 per day,” which would have come to $2,445, or about $56,715 today.

Earlier that year, in August, Francis B. Lane of Lane and Snyder would provide a receipt to Peter Cater for the amount of $3 for “2 days work at hawling [sic] pump Frame out of the canal.” This may have been a frame for one of the horse pumps, which (I’m guessing) would have been large, semipermanent chain-and-bucket installations.

I can find no other references to horse pumps in the commissioners’ reports or other state documents. But chances are they were used elsewhere when the expense was justified.

More interesting are the receipts that provide details on pump construction and repair.

Of particular interest is one issued by Lewis in January 1820 to Jedediah Richards for various items and services, including making patterns for culvert frames, a hammer pattern, three “pile Machienes,” making two pumps “at $7.00 per each,” and “for use of my pit saw.” Richards obviously worked with wood and may have been a sawmill operator – not an unusual occupation for frontier entrepreneurs. This strongly implies that the pumps were made of wood, perhaps from planks produced by his saw.

Richards is also a good example of a familiar early 19th-century archetype – the intrepid Yankee inventor. Between 1828 and 1832 he was awarded three patents: for a machine to punch iron and steel, a machine to manufacture window sashes, and for designs for an elevated railway and the “cars used thereon.” (An earlier 1810 patent, for a machine to manufacture excelsior, or wood wool, is credited to a Jedediah Richards 3rd, of Norfolk, Conn. – perhaps the same person.)

Further evidence that at least some of the pumps were made of wood is provided by a May 1827 receipt from contractor David Fitzgerald to Matthias Langdon for “making two box pumps.” Langdon would later be described by Jeptha Root Simmons in Frontiersmen of New York (Albany, 1882) as the “boss carpenter” of a crew that built a bridge in Fort Plain in 1828.

Blacksmiths provided many parts for pumps and repaired them, too.

A receipt from December 1818 from Lewis to James W. Redfield includes, among other items, “4 straps pumps . . . fix band for pump . . . 1 strap pump . . . 2 small bands for pump.” Local Onondaga County histories identify Redfield as one of the area’s early blacksmiths. What are “straps” and “bands”? I have some ideas which we’ll get into later.

An August 1823 receipt from contractor Caleb Hamill, who built a series of locks along the eastern end of the canal (and who figures prominently in Walter D. Edmond’s fictional narrative Erie Water), to blacksmith Nicholas F. Lighthall includes expenses for framing a pump box, “3 eye bolts for pump brakes,” and “repairing pump spears.”

In a piston pump, which is clearly being described here, the pump box is the chamber in which the piston works; a brake is the pump handle, and a spear is the rod that connects the handle to the piston.

A January 1819 receipt from Lewis to Casey McKay of Jordan includes “Leather to Leather the Boxes for two pumps” – perhaps the same pumps purchased earlier from Alvin Upham. About two weeks later another to Thomas Moseley mentions “Leathering pump boxes for the use of the Erie Canal at Jordan aqueduct.” Many other receipts refer to leather work.

Finally, an example that brings us full circle: a May 1825 receipt to Richardson and Beals for “items of extra work done by them in their subcontract on the Erie Canal through the Cayuga Marshes.” The items include “excavating pump pits below bottom in order to prepare for pumping.”

Summing up

A few things seem to be coming into focus.

First, several kinds of water pumps of various shapes and sizes were likely used along the canal. Many seem to have been fabricated by local craftsmen along the line.

Second, aside from the large horse pumps on the Mountain Ridge and a single reference elsewhere to “screw pumps,” most appear to have been hand-powered piston lift pumps.

Third, some if not most pump boxes were made of wood, and fittings and moving parts were forged from iron. Pump boxes may have been lined with leather to provide a watertight seal, and pistons may have been made of leather.

Fourth, where it was important to completely drain the excavation, pump pits would be dug into the bed of the canal prism. Perhaps the pits were lined with stone or timber to reduce the amount of mud and debris that might clog the pump.

Finally, judging from the quantity of receipts for repair work, these machines regularly broke down and had to be fixed, maybe by the same hands that built them in the first place.

So what did they look like? We’ll explore that in part two.

A final note for those who stayed with me to the end. If you or someone you know is familiar with 1820s construction technology, I’d appreciate hearing from you. Leave a comment here, or contact me via email at smb (at) steveboerner (dot) com.