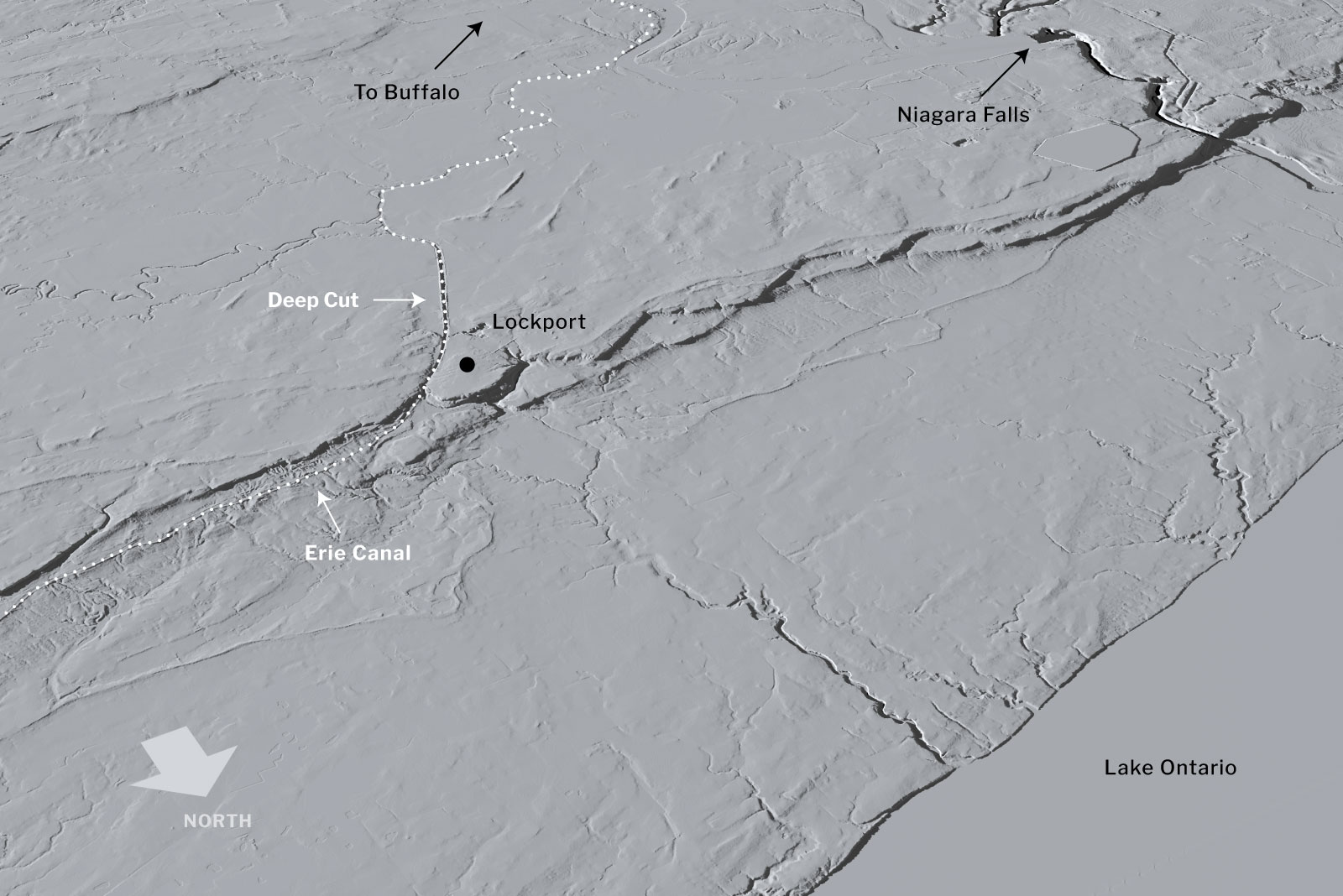

The Deep Cut was the last section to be finished on the original Erie Canal. For nearly five years canal planners and engineers had watched with increasing frustration as an army of immigrant laborers gradually chipped and blasted its way through the solid rock of the Mountain Ridge.

Now known as the Niagara Escarpment, the ridge is composed largely of Lockport dolomite and extends across western New York. It forms the ledge that Niagara Falls tumbles over 20 miles to the west. And in the 1820s it stood squarely in the canal’s path.

There was no alternative: The canal had to go straight through the ridge to reach Tonawanda Creek to the south, and then on to Buffalo and Lake Erie. To maintain a water level equal to Erie meant digging more than thirty feet deep in places. Through solid rock. With hand tools and primitive blasting powder.

“Through that ridge,” wrote the state’s canal commissioners in their annual report for 1822, “occurs the most extensive deep cutting, which we have any where to encounter. It is, in truth, very formidable, and exceeds seven miles in length.”

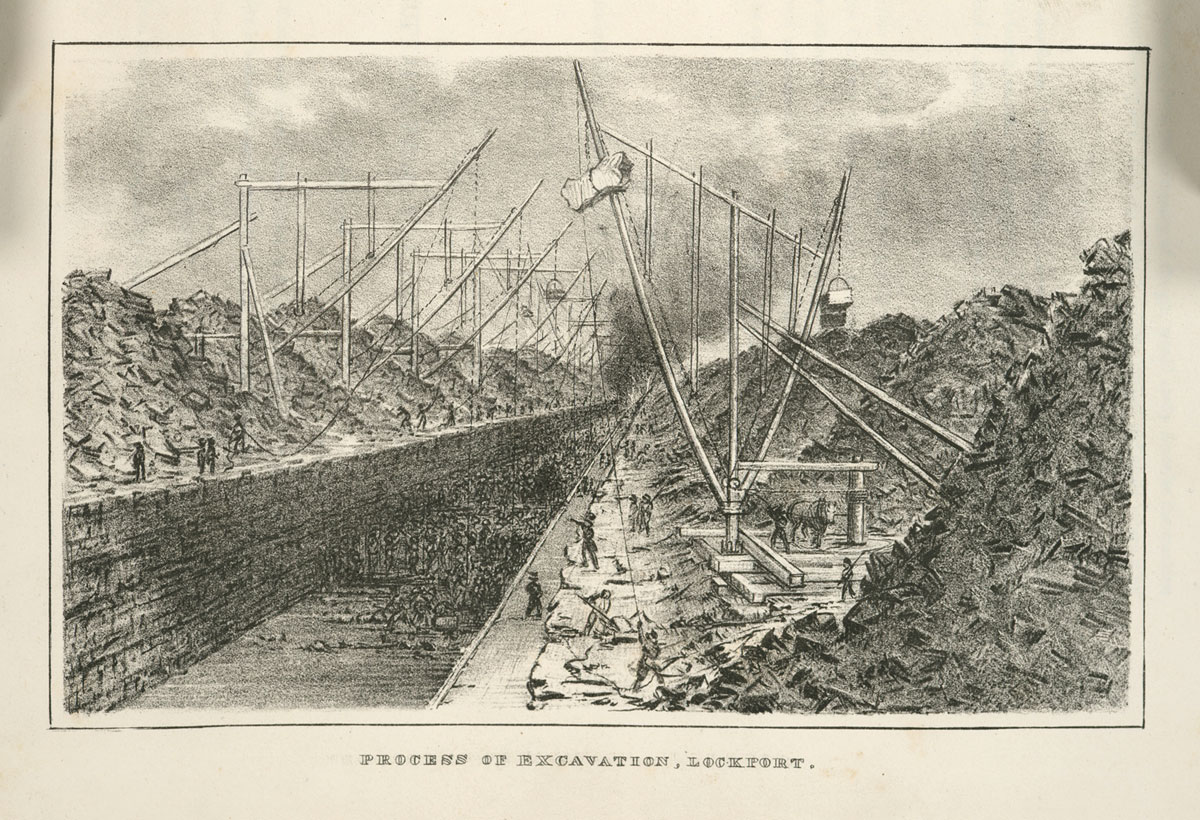

The excavation of the Deep Cut will make an excellent subject for a digital scene. To a large extent it will be inspired by George Catlin’s well-known lithograph, Process of Excavation, Lockport, which may be the only contemporary depiction of the effort.

Catlin, who would later become famous for his portraits of Native Americans, was commissioned to execute a series of scenes to commemorate the canal’s completion. His sketches were among the first lithographs printed in the United States when they appeared in Cadwallader Colden’s Memoir in 1825.

As art, Process of Excavation is undeniably dramatic. Lowering clouds and towering piles of rubble frame a deep vertical cut in which masses of men break and haul stone. Explosions roar in the distance. Overhead, spindly horse-powered cranes haul out the rubble to raise in piles fifty feet above the canal’s banks, according to the accompanying text in the Memoir.

The image has a certain Dante-esque feeling to it, of men laboring ceaselessly in the first circle of Hell.

As a historical reference, however, the lithograph raises a few questions. The rock piles seem too steep and too high, the canal cut too wide. There is little detail in the cranes. In fact, there is remarkably little detail anywhere. The indistinct mass of laborers in the bottom of the cut blends right into the rock walls.

Our goal will be to build a scene that is historically accurate and physically realistic. And despite the questions that remain, there’s no harm in starting on some of the details.