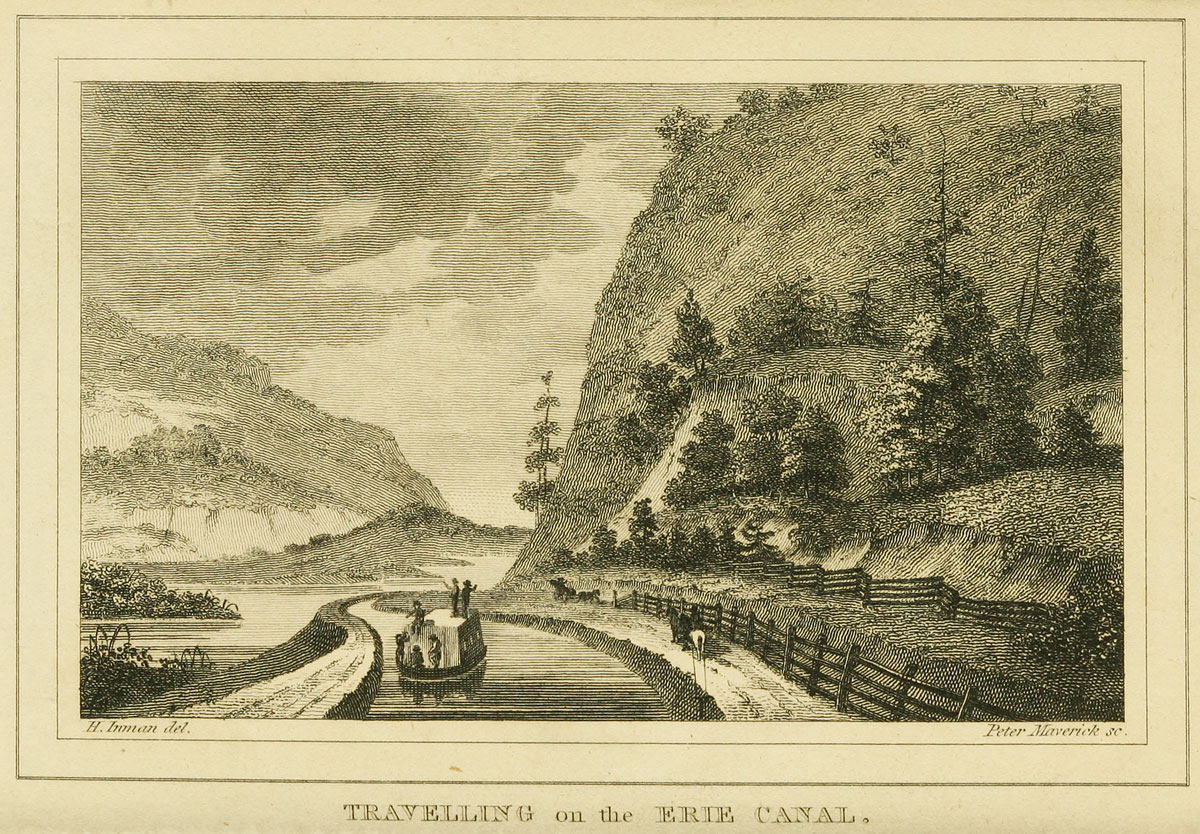

The subject of the next Erie Canal scene will provide a welcome change of pace. Instead of the scarred and blasted landscape of the Deep Cut, we’ll go to a place where the canal engineers accommodated nature, where the canal’s gentle curves paralleled the Mohawk River as both made their way toward Albany and the Hudson River.

The place is known as The Noses, named for two cliffs that frame a narrow gap in the hills. The Mohawk flows between them as it crosses the Appalachian ridge, forming the only east-west water route that breaks through that mountain barrier over its entire extent from Maine to northern Alabama. It is the key geological feature that made the Erie Canal possible in the first place.

The Noses themselves are landmarks with references dating back to the colonial era. Back then, the larger cliff was known as “Anthony’s Nose.”

Anthony’s Nose, on the north side of the Mohawk, is today simply called “Big Nose.” Facing it across the way, on the south side, is Little Nose. The gap in between is an historic line of communication, and after the canal was built the railroad soon followed. Today, the New York State Thruway (Interstate 90) takes the same route.

A children’s book published in 1852, Marco Paul’s Voyages and Travels: Erie Canal, describes a trip through the gap by rail:

“For there is a place here called the Pass of the Mohawk. It is where the river flows through a narrow passage in the mountains, with extensive ledges of rock and lofty cliffs on either hand. As the train of cars advanced up this defile, Forester and Marco perceived that the mountainous ranges approached nearer and nearer, until the river, the turnpike, the railroad and the canal were crowded close together and Marco could look down upon them from the window of the car, running side by side, and hemmed in on either hand by precipices of ragged rocks.”

Historical references

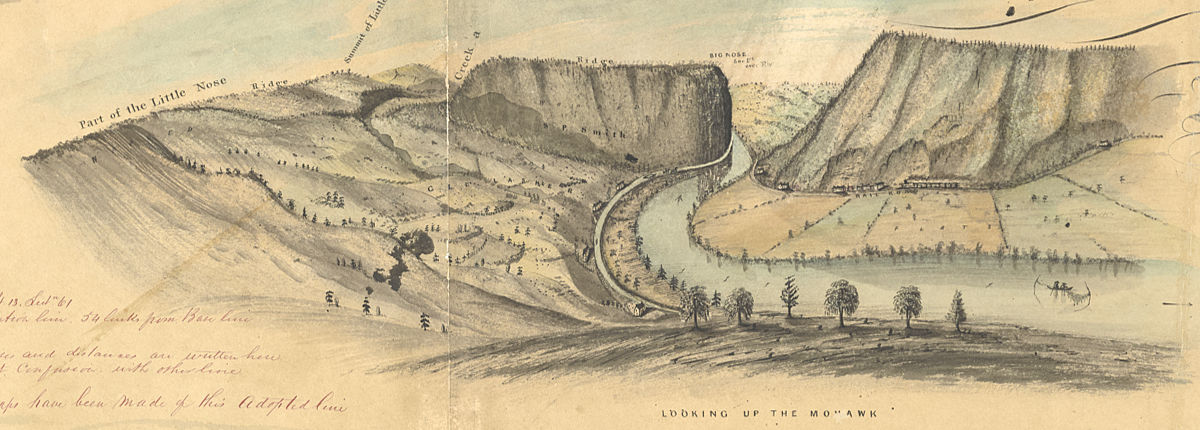

There is a wealth of visual information about this area, dating from an 1811 survey map drawn by Benjamin Wright, who later became the Erie Canal’s chief engineer. We also have a spectacular map created by draftsman David Vaughan in 1851. Vaughan’s map is useful because it features detailed drawings – one of his hallmarks – that provide clues to the state of the landscape. Today the area is mostly covered with second-growth woods. But in the early 19th century much of it would have been cleared for farming.

Even more valuable are the so-called Holmes Hutchinson maps of the Original Erie. These were the result of a survey of New York’s canal system commissioned by the state legislature and carried out 1832–1843. The maps, beautifully executed in in ink, wash and charcoal, depict the canal line at a scale of two chains — 132 feet — to the inch. There are nearly 1,000 altogether, and high-resolution scans of all of them are available at the New York State Archives website.

The map shown here locates the foreground of the scene, so it and its neighbors will be used to help reconstruct the area as it would have appeared in the early 19th century.

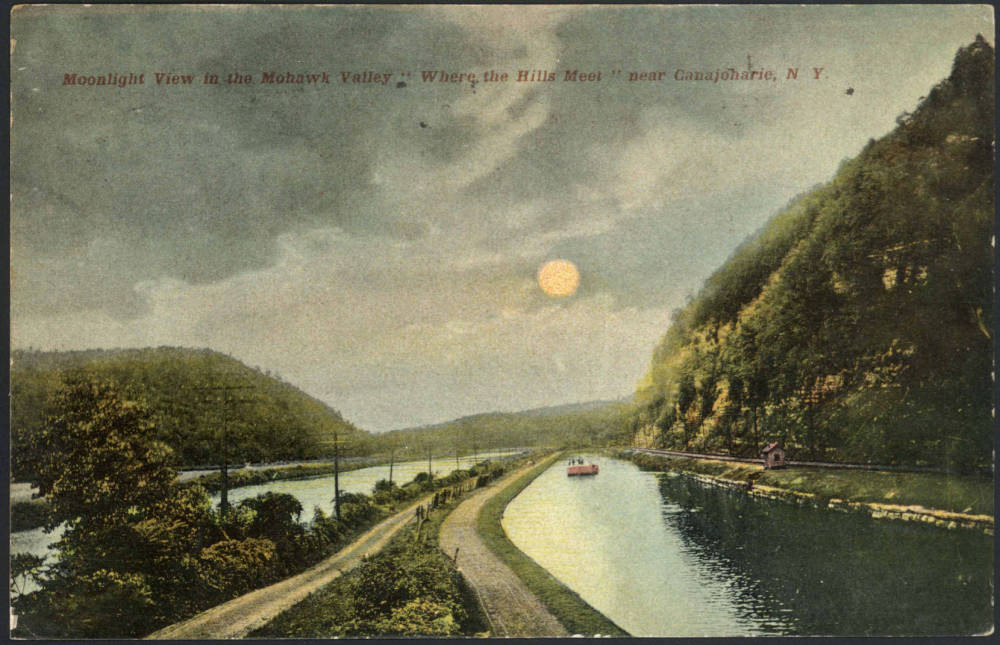

Several postcards, printed in the early 1900s, also survive. The original Erie Canal was long gone by then, superseded by the mid-19th-century First Enlargement. But they depict the Noses and Mohawk River before the final Barge Canal enlargement and the incursion of the New York State Thruway, both of which dramatically altered the topography of this historic corridor.