Our Erie Canal laker model, shunted into digital dry dock last spring, will be expanded into a small fleet for our scene.

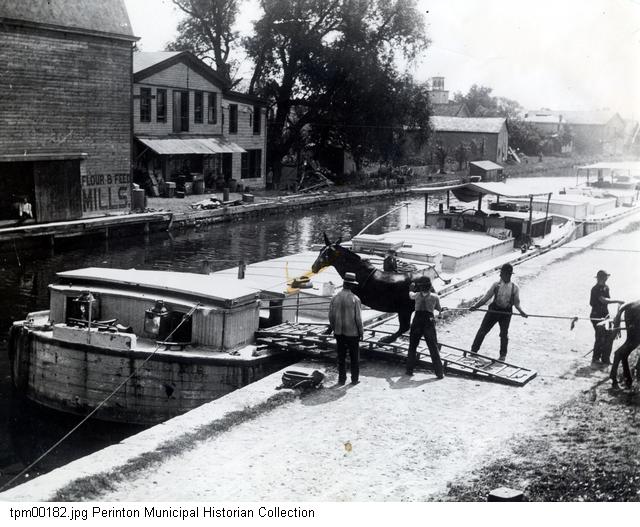

Of all the types of boats on the Erie Canal in 1916, the laker was the most common. Unpowered (or, in the jargon of the time, “unrigged”), it was the workhorse of the Erie Canal from the late 19th to the early 20th century. According to a Report on the Ship-Building Industry of the United States, published in 1884 by the U.S. Department of the Interior:

“The laker is a regularly framed boat, with perfectly flat bottom, square bilge, perpendicular sides, straight body, round bow and stern, and decked entirely over. It is made of oak and white pine . . . and it is 97 or 98 feet long, 17½ or 17⅔ beam, and 10 or 10½ feet in depth of side. . . .”

These boats . . . weigh from 65 to 72 tons, and carry 225 to 240 tons of cargo. They are usually painted white, and the stern is often profusely ornamented by a sign-painter, the name and home port being conspicuously painted in gilt and red and blue letters. About one-half of the boats on the Erie Canal are of this type. Being good for almost any service, these boats . . . are popularly used in forwarding grain from Buffalo and Oswego to New York city [sic] via the canal and the Hudson River.

In 1883 a newly built laker cost an average of $3,800, roughly equivalent to $95,000 today. It would see service for 10 to 15 years, perhaps longer if it were well maintained.

For much of this period most canal boats were animal-powered. A team of three mules, walking along the canal’s towpath, could pull two fully loaded lakers lashed together. These doubleheaders would allow the owner to maximize his or her carrying capacity (and profit) with a minimum crew.

That crew, which often included family members, lived in the aft cabins. The animals were housed in the bow cabin or bowstable. Two teams of three mules were switched every six hours and kept the boats moving 24 hours a day. The speed limit was 4 miles per hour – a brisk walking pace – but most boats averaged less, covering the 360 miles between Buffalo and Albany in five to seven days.

From 1880, steam-powered boats began to replace animal power. By 1916 – the date of our scene – the transition was virtually complete. Steel barges, another innovation, had made an appearance but their adoption would be interrupted by World War I, when all steel production would be diverted to the war effort.

So for the time being wooden lakers would be pushed and towed by wooden steamers. (There will be more about steamers in the next post.)

When they reached the end of their useful lives, wooden canal boats were often simply abandoned by their owners at “graveyards” where the canal was wide enough to accommodate their decaying wrecks.

One old graveyard can still be seen along the canal in Pittsford, New York, where the sad, old frames are exposed when the canal is drained for winter. It’s amazing that they have survived for so long.