One of the most enduring myths about the Erie Canal is that it was built by Irish immigrants. In fact, the majority of its 363 miles were contracted out to and dug by native New Yorkers. In their 1819 report, the canal commissioners had proudly reported that “three-fourths of all the labourers” working on the canal “were born among us.”

But there are many reasons why the tale of Irish workers has been so persistent.

To begin with, by the commissioners’ own account fully one-fourth of the laborers working on the canal during the first full year of construction were immigrants. While that group would have included people of many nationalities, most probably came from Ireland. As work progressed that number grew until Irish workers predominated along certain sections of the canal.

Those sections were among the worst places to work along the line. They included the Cayuga Marsh, the Great Embankment, and the Deep Cut. Native-born Americans, it seems, were more than willing to leave the dirtiest, most dangerous work to the latest arrivals.

Predominantly young, male and single, the Irish brought from the old country entrenched notions about masculine behavior, a strange religion, and a stranger language. They soon earned a reputation for fighting, which “native” Americans attributed to the bottle, because the Irish had a reputation for that as well.

By all accounts, they were a rough bunch.

But antebellum American society already was violent, especially along the frontier. Americans of all classes, to put it mildly, drank like fish.

But the stereotypes became excuses to keep the newcomers in their place. In Lockport they were relegated to drafty, squalid shacks along the excavation and in “Lowertown,” while established citizens maintained a prosperous, middle-class existence in the “Upper Village.”

The Irish workers’ reputation for violence and drink may well have been exaggerated. We will never know for certain, because the workers themselves and their families, for the most part, were illiterate and left behind no records.

But when all was said and done, the Irish and other immigrant workers completed the tough, miserable task of excavating the Deep Cut. They dug, and drilled, and died — in explosions, from falling rocks, from disease. Over four long years they chipped and blasted their way through the Mountain Ridge, overcoming that final obstacle to open the canal from Buffalo to New York City.

Populating the scene

In his book, Stairway to Empire: Lockport, the Erie Canal, and the Shaping of America, historian Patrick McGreevy uses surviving expense vouchers to estimate the crew sizes for several contractors working in the Deep Cut. He calculates an average crew size of 94 men, yielding a total workforce of 2,068 for the 22 contracts that were active through July 1824.

This is a larger figure than the 1,500 men mentioned in Colden’s Memoir. Regardless, the size of the workforce was unprecedented in this country.

Because the excavation on the Mountain Ridge had been going so slowly, New York in 1822 assumed direct supervision of all of the contracts there, turning the contractors into middle managers paid by the state. More workers were recruited and others shifted to the summit from other sections of the canal to achieve this remarkable concentration of labor.

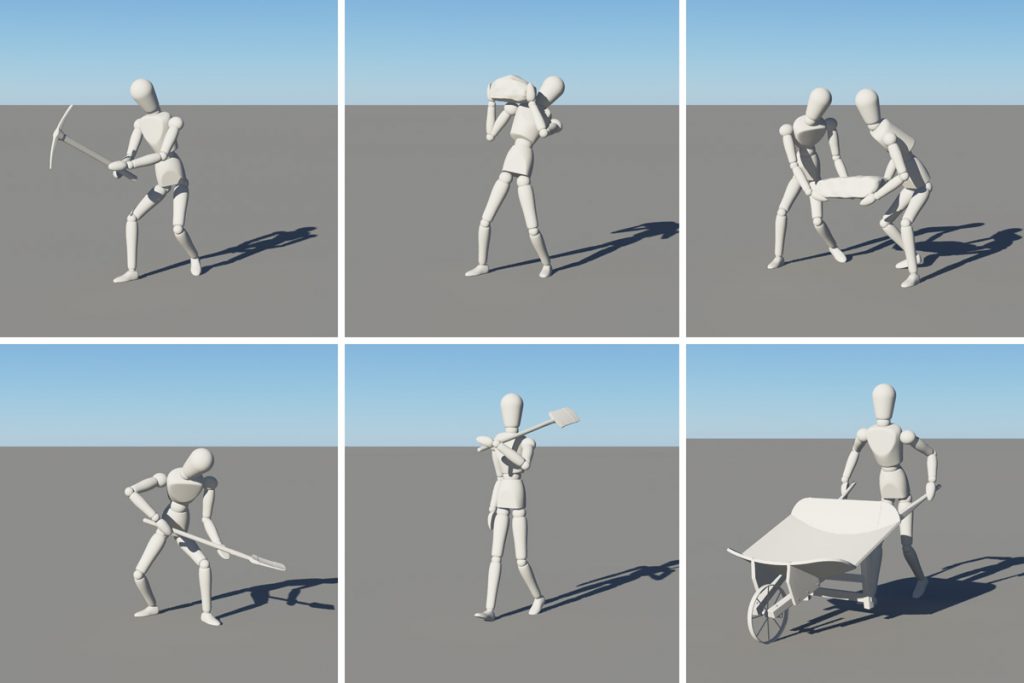

McGreevy’s estimate gives us a good idea of the number of workers that will be needed for the Deep Cut scene. It depicts a single contract, so we’ll need about 100 human models.

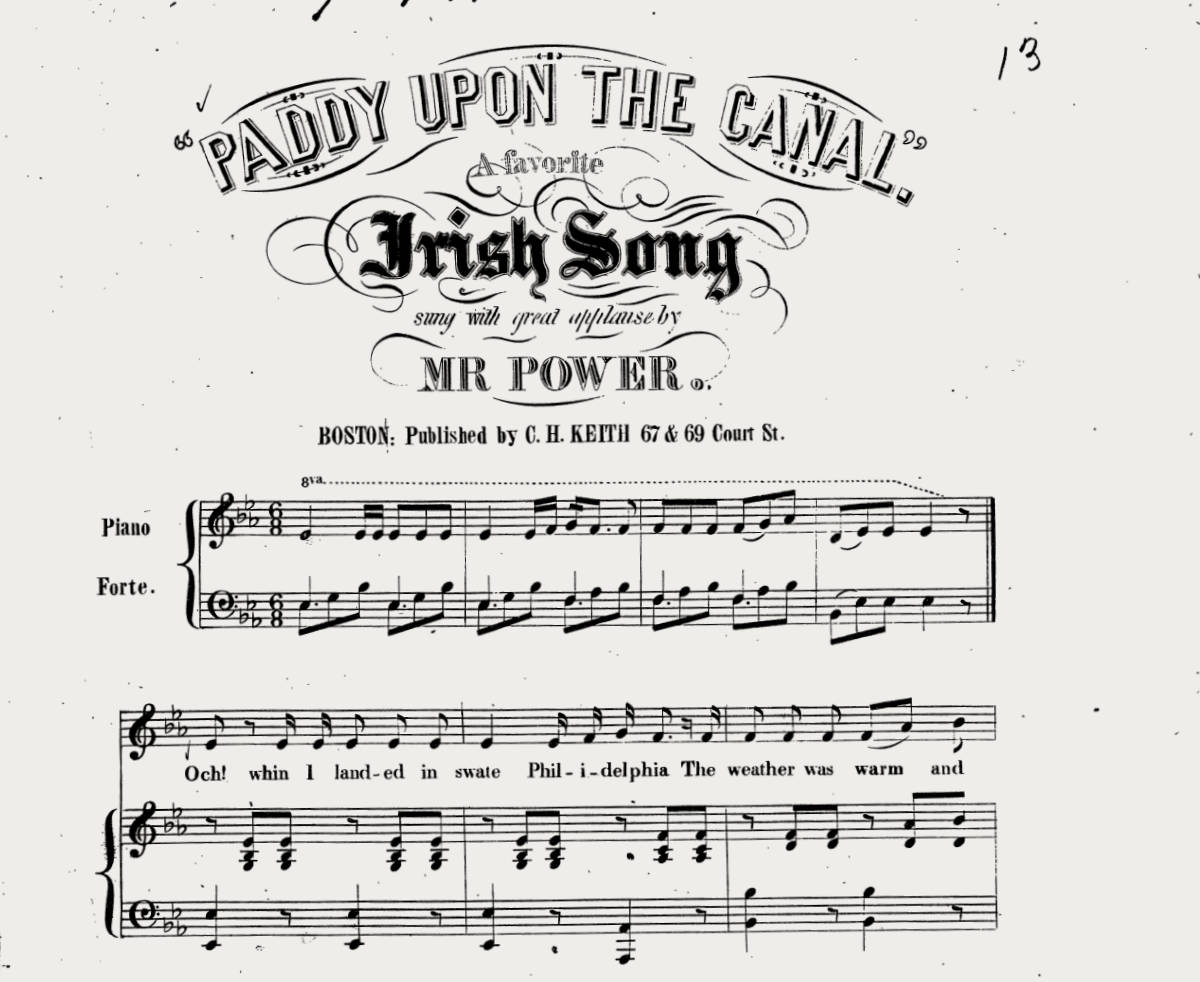

Of course, we don’t need 100 unique models to accomplish this. Duplicates can represent groups of workers, especially in the distance. To figure out the number of models that would be needed, I put together a simple mannequin model and used it to quickly make a series of poses, eventually winnowing the number down to about 20.

The selected mannequins were placed in the scene. This eliminated a lot of guesswork and helped to create a list of figures needed, their poses, and locations. After that it just became a matter of setting up a pipeline to produce the actual human models. This post includes a test renderings of a few that have been completed, and more are on the way.