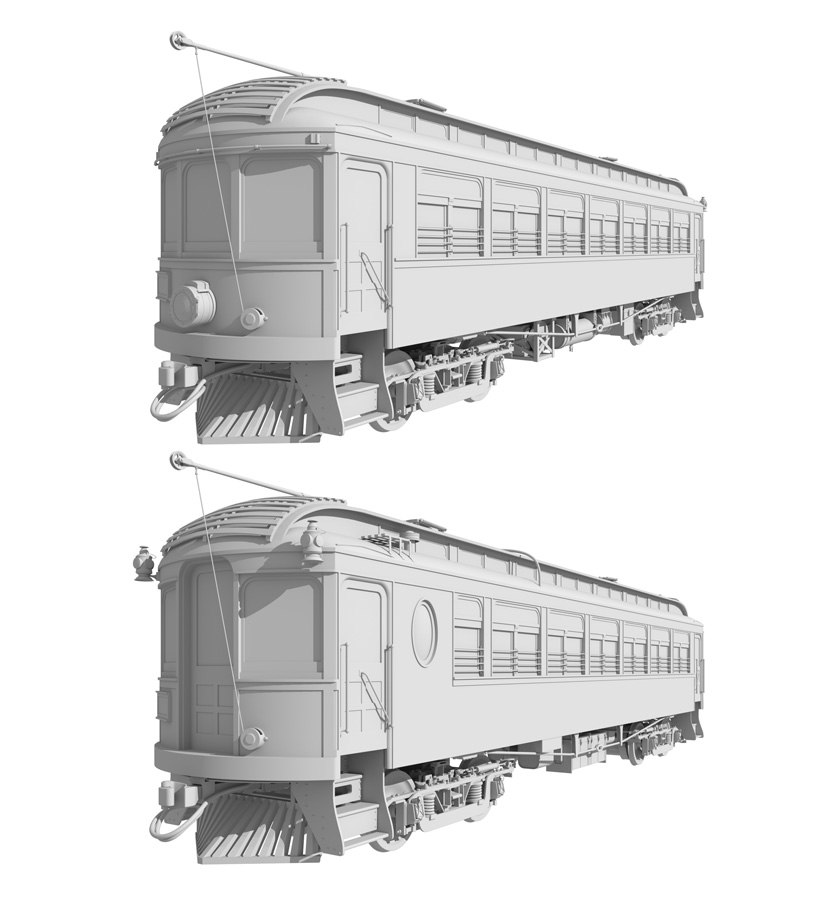

Summer has been busy and opportunities to work on the Adams Basin scene somewhat scarce. So far all available time has been spent developing a set of good quality human figures. The base models are done and mostly rigged and I’m now fine-tuning the skin weights. As that work slowly progresses I’ve decided to take a break to do something a little more quick and fun.

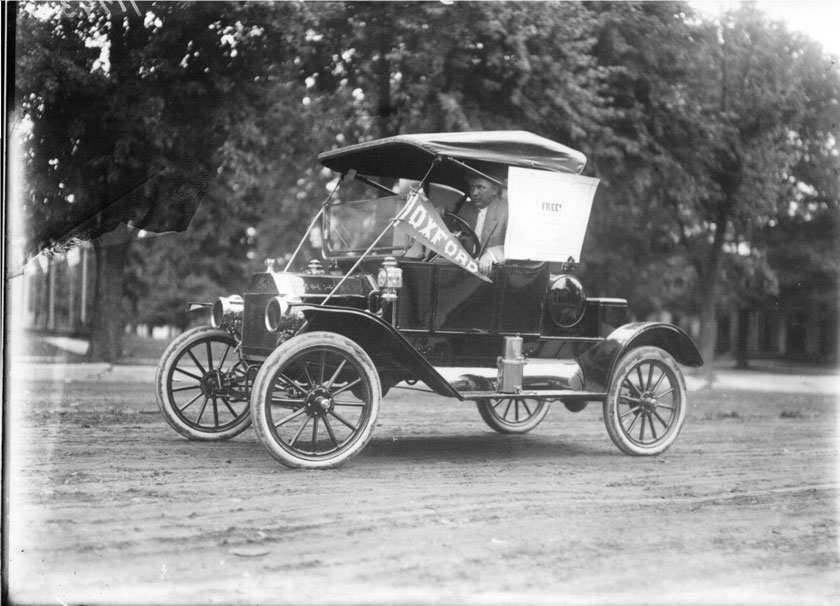

The scene seems to have an emphasis on transportation so the obvious thing to add is a motorized vehicle – a Ford Model T.

And not just any old Model T. Since this is my scene I’ve decided to add a particularly interesting version of the T – the 1912 Ford Torpedo Runabout.

The Model T, of course, was the electric interurban railroad’s nemesis. Introduced at about the same time – 1909 – Henry Ford’s “universal car” was initially dismissed as an expensive novelty that would never compete with the railroads, steam or electric. But no one anticipated Ford’s genius for mass production and marketing. The price of the T quickly dropped year over year as the numbers produced grew. And soon it became the answer to the problem that the interurban had struggled to solve – providing simple, reliable transportation for the country’s rural population.

The 1912 Ford Torpedo Runabout was introduced in October, 1911. The new model eliminated some of the racier aspects of the 1911 Torpedo, which had a longer hood and lower seat, perhaps to make it easier to manufacture. As far as I know the 1912 model year is the only year that this particular car was produced. The cost was $590, a not insignificant sum in those days, equivalent to about $16,000 today. It was one of two model Runabouts produced for 1912, and between them 13,376 were manufactured that year out of a total of 68,773 for all T models.

Altogether around 15 million Model T Fords were produced from 1909 through 1926, and out of those perhaps a half million survive today. Out of those, it is said that around 200,000 to 300,000 are still drivable.

Which explains the large and enthusiastic T community and its equally large and enthusiastic online presence. There’s lots of great information about the T on the web.

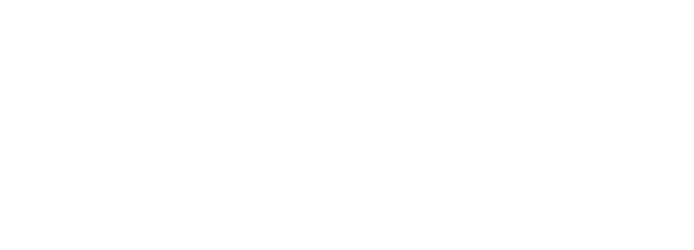

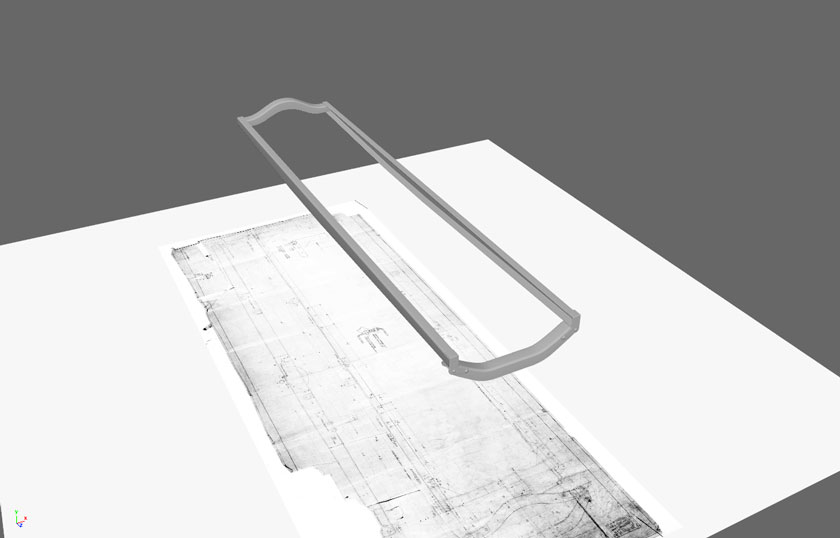

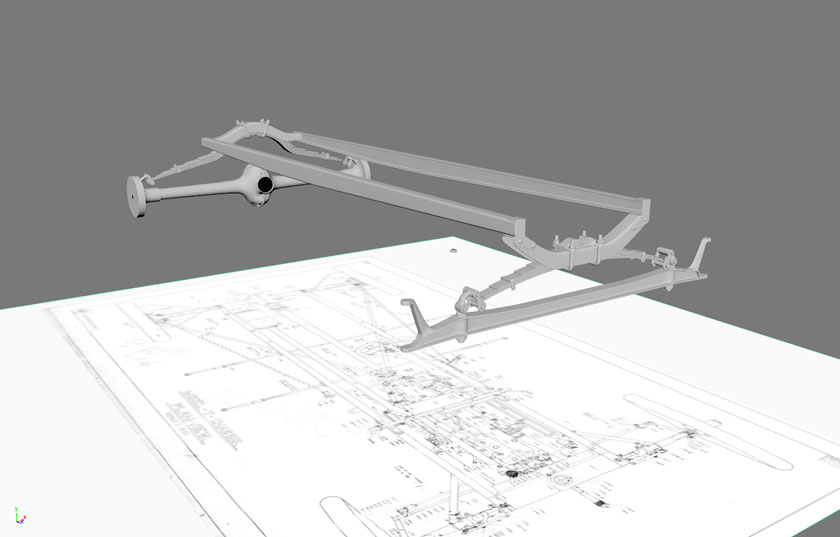

The reference drawings I’m using are period Ford blueprints now held on microfiche at the Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan. Other information has been gleaned from Model T Ford Fix (the most impressive blog on any subject that I’ve ever run across) and the Model T Ford Club of America’s extensive online Encyclopedia. The folks at MTFCA have been helpful as well. Plus many other online sources too numerous to list here.

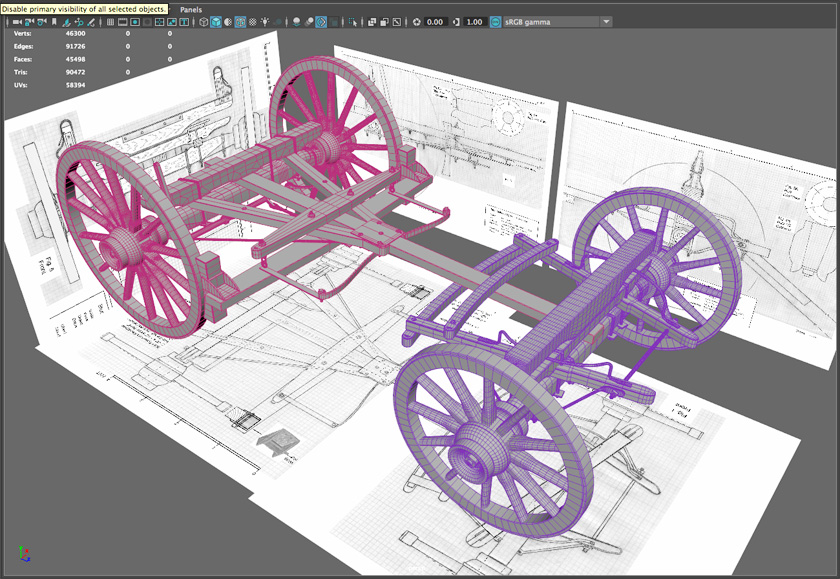

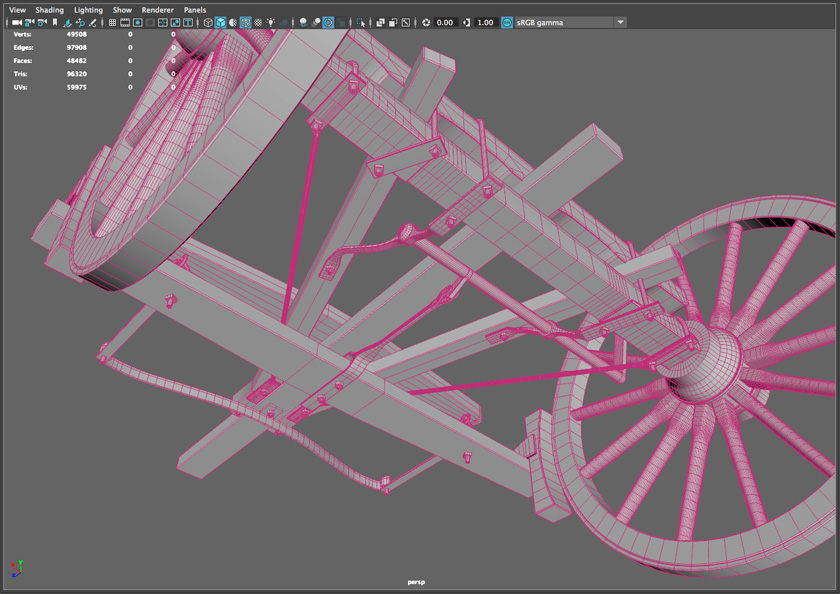

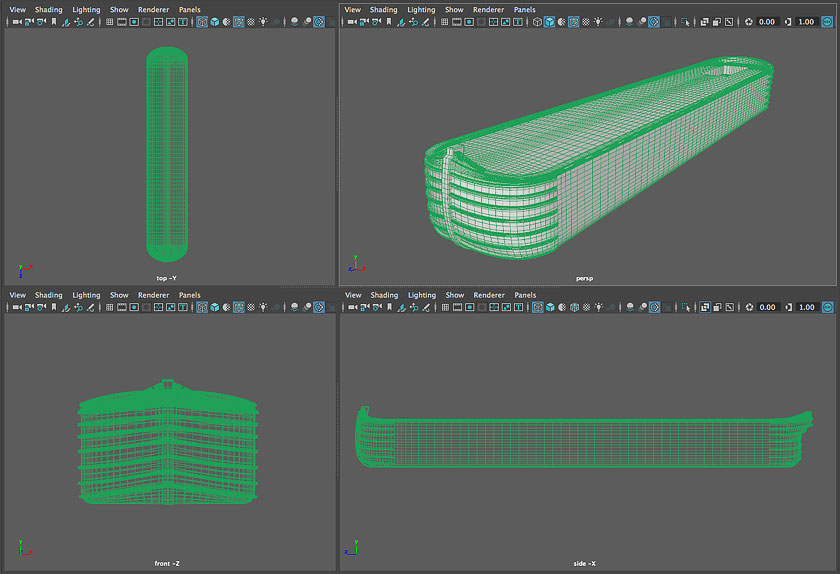

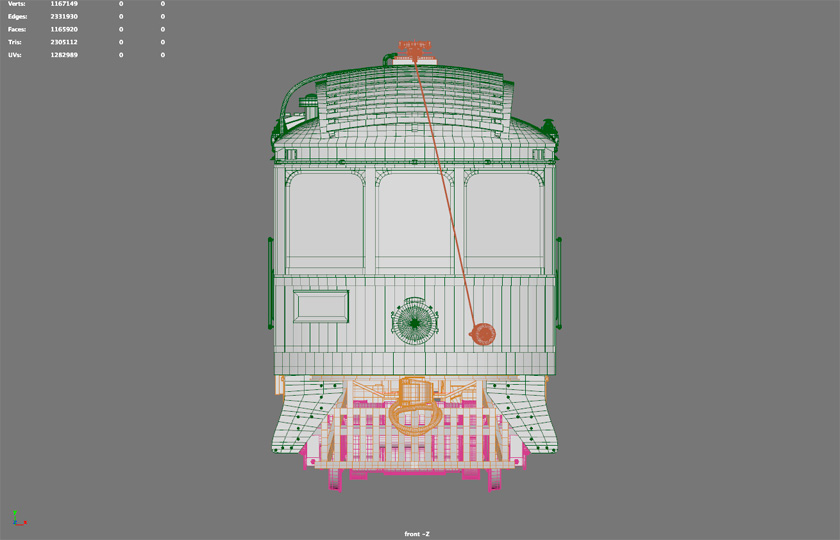

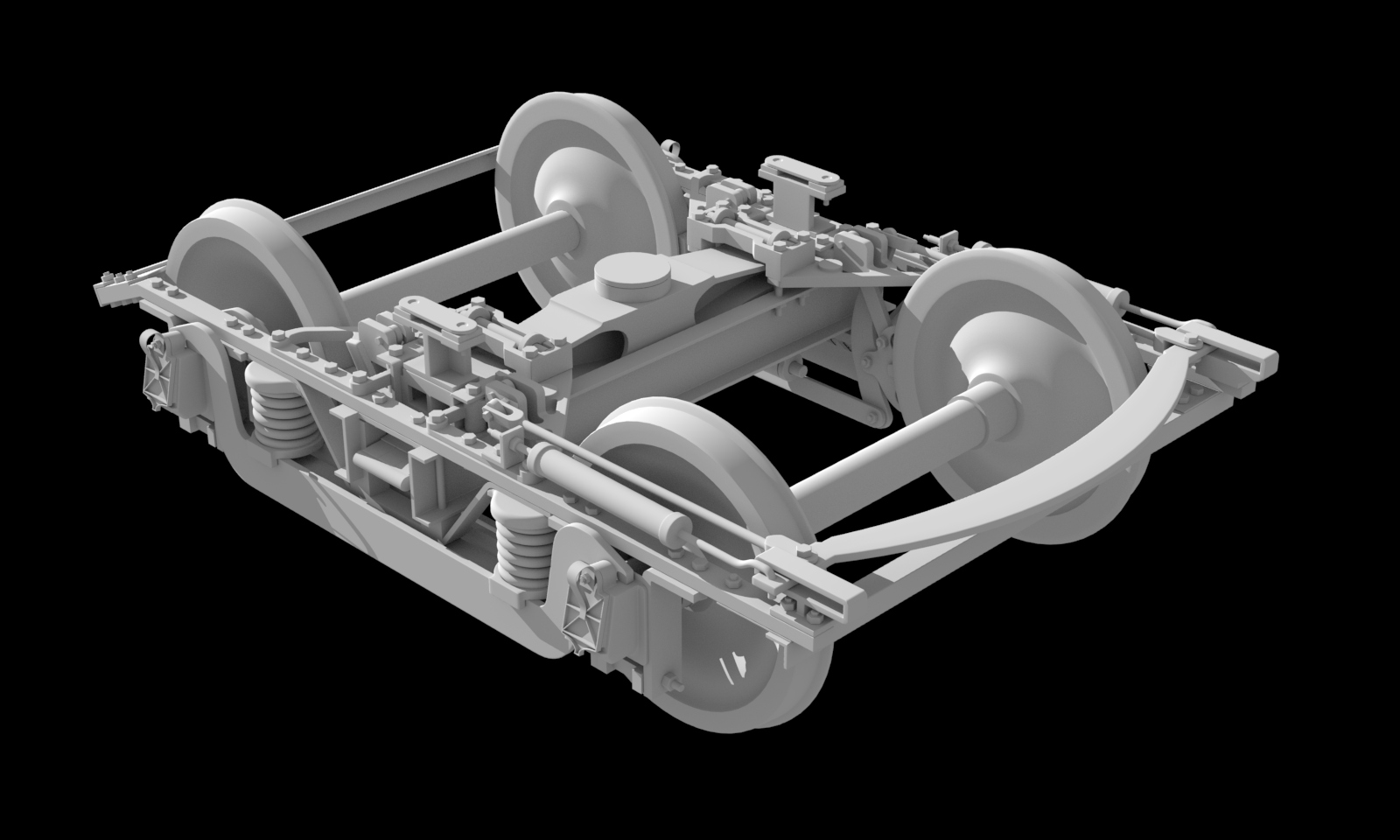

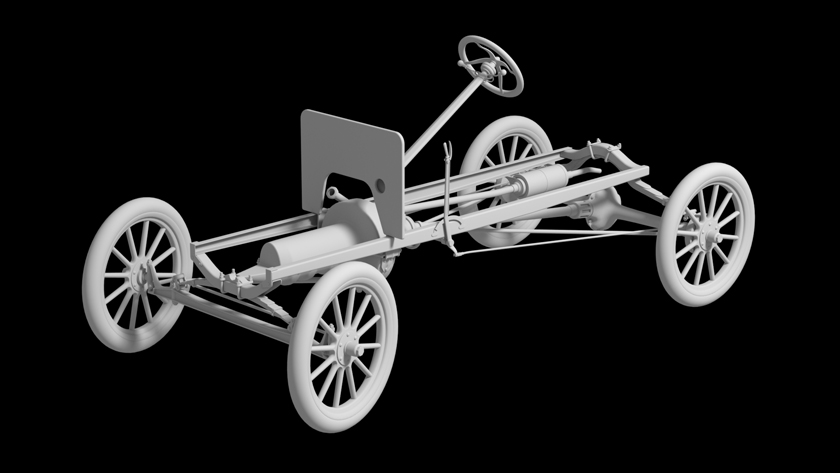

All 1912 Ford Model T automobiles were built around the same chassis, which was itself based on a simple steel frame long enough to accommodate the car’s 100-inch wheelbase.

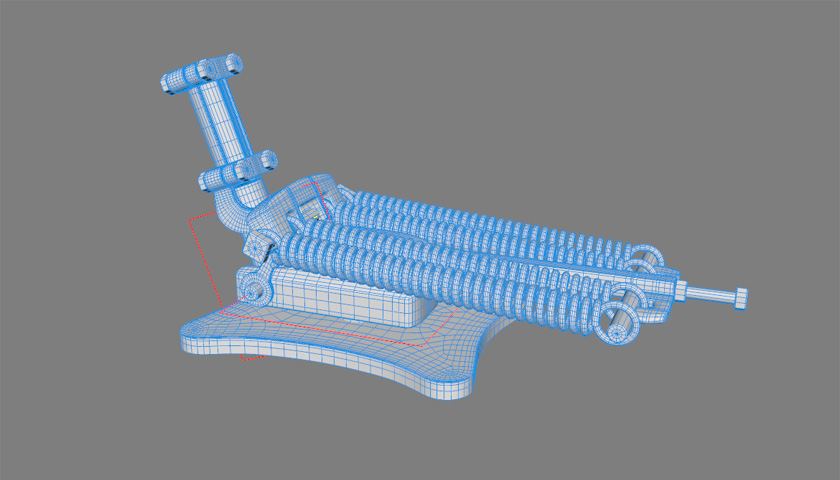

Leaf springs attach the frame to the front and back axles and provide the basis for the T’s legendary, rugged suspension.

After adding wheels, dashboard, steering and brake gear, the 1911 chassis is nearly complete. There are two options now since I have body plans for both the 1911 and 1912 Torpedo models. The chassis will need a few minor modifications for 1912 but otherwise is good to go either way. The drawings for the 1912 Torpedo are more complete – and its purchase date nearer to the 1916 date of the scene – so I’ll probably go with it.