Of all the accounts of the early Erie Canal, this one holds a particular appeal. If you are an American of Norwegian descent, chances are you’re familiar with it. If not, read on. It’s a good story.

By the early 19th century first-hand accounts of life in the United States were beginning to reach ordinary people on the other side of the Atlantic. Stories of rich farmland ready for the taking and freedom to worship were hard to ignore.

Among those listening was a community of people in Stavanger, Norway, the core of which consisted of a small group of Quakers facing discrimination from their country’s Lutheran government. They dispatched an agent to America to investigate. When he returned with a favorable report and title to farmland bordering Lake Ontario in upstate New York, they pooled their resources, purchased a 54-foot sloop named Restoration, and made plans to emigrate.

A prominent member of the group, a ship’s carpenter named Lars Larson, and his wife, Martha, joined 50 other passengers and crew and set sail on July 4, 1825. After a harrowing 98-day voyage across the Atlantic – during which Martha gave birth, increasing the ship’s complement by one – the weary immigrants bravely sailed into New York harbor on October 9.

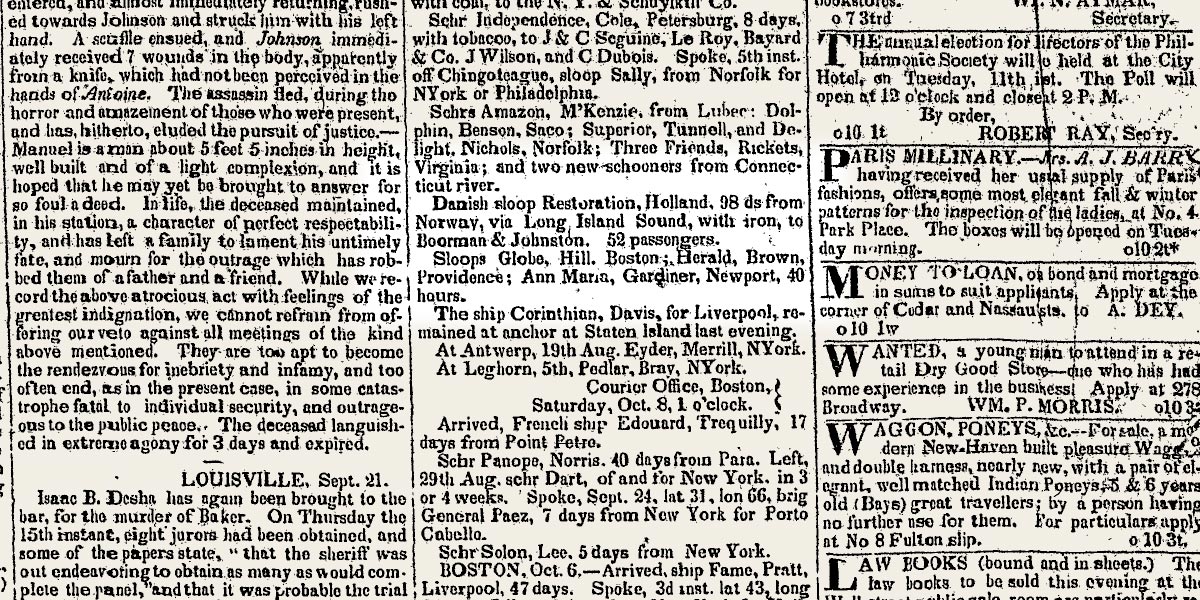

The occasion was noted by the New York Daily Advertiser in an item reprinted in newspapers across the Northeast:

“A novel sight. — A vessel has arrived at this port, with emigrants, from Norway. The vessel is very small, measuring as we understand only about 360 Norwegian lasts, or forty-five American tons, and brought forty-six passengers, male and female, all bound to Ontario county, where an agent, who came over some time since, purchased a tract of land. The appearance of such a party of strangers, coming from so distant a country, and in a vessel apparently ill calculated for a voyage across the Atlantic, could not but excite an unusual degree of interest. They have had a voyage of fourteen weeks; and are all in good health and spirits.”

The warm welcome did not last. Within days the Restoration was seized and its captain jailed by the U. S. Customs Service. United States law restricted the number of passengers that could be carried by arriving vessels, and the tiny, dangerously overloaded sloop carried 21 passengers over the limit.

The Sloopers, as they were soon christened, had hoped to sell the Restoration upon arrival to pay expenses. Instead, their ship had been impounded and they were facing a fine of $3,150. But the local Quaker community rallied and financed the final leg of their journey, first by steamboat to Albany, then west on the newly completed Erie Canal.

According to tradition along the way they encountered the canal packet Seneca Chief, bearing Governor DeWitt Clinton, other dignitaries, and two casks of Erie Lake water en route to New York and the “wedding of the waters.” The westbound boat would have had the right of way, so the Seneca Chief dropped its towline and pulled aside, saluting the new immigrants as they passed.

After disembarking at Holley, the hardy Sloopers walked the final 10 miles north to their homesteads in the town of Kendall.

Larson and two others had remained behind to sort things out. They appeared before Judge William Peter van Ness of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on October 14 with a petition that was forwarded to President John Quincy Adams, who issued a full pardon on November 15.

Larson made his way to Albany, where he found the canal frozen solid. Undeterred, he purchased a pair of ice skates and skated the 300-mile distance along the canal to be reunited with his family.

So the story goes.

Fact or fiction?

Some of the information for this post is drawn from a paper published in Norwegian-American Studies, the journal of the Norwegian-American Historical Association. In it the author, Richard L. Canuteson, wryly notes that over time some of the story’s retelling “has been based upon careful investigation, part of it on erroneous interpretation or translation, and part on family tradition — which by its very nature and the method by which it has been passed down from one generation to another may be less than accurate.”

While the arrival of the Restoration and ensuing court case are well documented, the account of Larson’s extraordinary trek along the iced-over canal at first appears to be a traditional embellishment. But hold on.

Long-distance skating, or tour skating, is popular today in Nordic countries. A cursory Internet query turns up the fact that casual tour skaters can skate up to 30 kilometers a day, while more experienced skaters can travel up to 100 kilometers — or more. Average speeds vary between 10 and 20 kilometers, roughly 6 to 12 miles, per hour.

At 6 miles per hour Larson could have completed the trip in 50 hours, or five grueling 10-hour days. He would have been hindered by obstacles: locks, stranded boats, uneven ice. But someone who had survived a 98-day Atlantic crossing may have looked at this as just one more thing to take in stride. Under the right conditions, he could have done it.

But what were the conditions?

On October 10, 1825, the same day it announced the arrival of the Restoration, the New-York Evening Post also published a small item about the weather. “We have experienced several days of unusually warm weather for the month of October,” it read. “Last Sunday the thermometer stood at 85.”

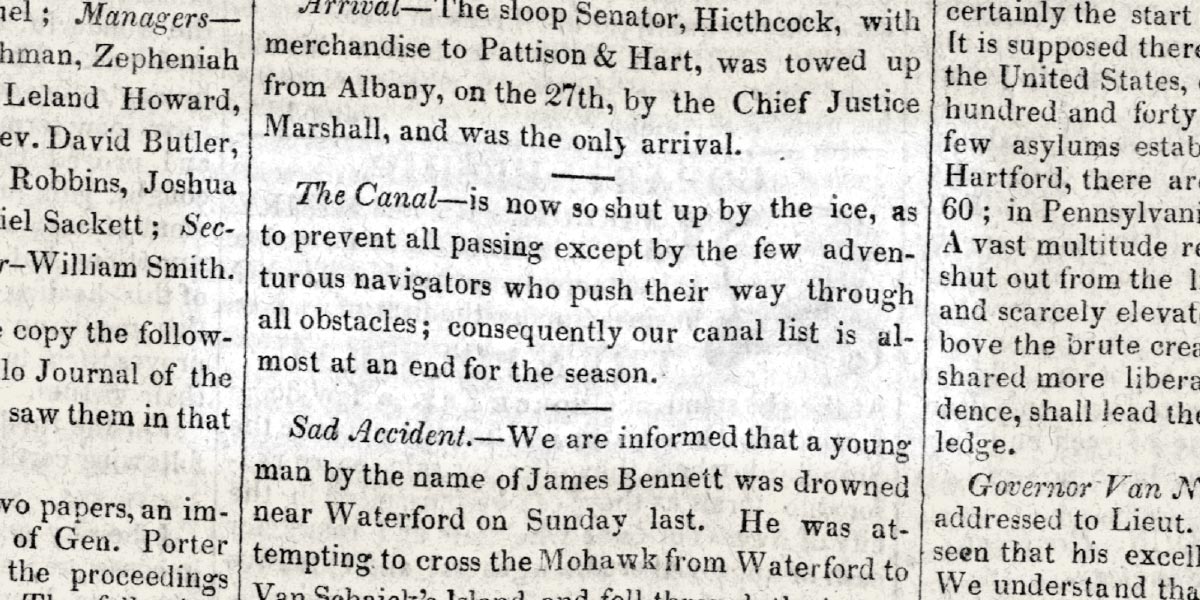

Recall, though, that this is upstate New York we’re discussing here. A few short weeks later the story was very different. On November 22 the Evening Post reported that “above Schenectady the canal was partially closed with ice. . . . But last evening the weather was greatly moderated, and we have hopes that canal navigation will be free a few days more.”

On November 30 Canandaigua’s Ontario Repository wrote that the “Buffalo papers state that the Packet Boats between there and Rochester, have stopped running for this season. The cold weather we experienced a few days since, closed the canal in several places.”

According to state records, the canal that year was officially closed to navigation on December 5. But these newspaper items show that during the final weeks navigation was an on-again, off-again affair as traffic struggled against the encroaching ice. Packet lines, sensitive to any interruptions, would have halted service weeks earlier.

So by the time Larson reached Albany it’s likely that much of the canal was covered with ice “several inches thick.” Even if the canal wasn’t frozen end to end, he could have skated the iced-over sections while walking or finding other transportation in between. His long-distance ice-skating feat, the stuff of legend, may be based on fact.

Lars and Martha settled in Rochester, where he prospered as a boat builder alongside the new canal. Over the years their home in the city’s Third Ward (now the Corn Hill neighborhood) became a way station for thousands of Norwegian immigrants making their way west.

Sadly, Larson’s life ended unexpectedly by drowning in the canal that had carried him into America and on which he made his living. His body was recovered from a lock near Schenectady on November 13, 1845. He was 59 years old. To the end of her days Martha maintained that Lars had been murdered, pushed into the icy water in the course of a business deal gone bad. But nothing was ever proved.

Within a few years of their arrival most of the Norwegian families of Kendall, disappointed with the poor quality of the land, moved to a new community along the Fox River in Illinois. Today a handful of Norwegian surnames in the Kendall phone directory, the signposts along Norway Road, and a couple of historical markers are among the few reminders of the original Slooper settlement.