Before the Erie Canal, there was the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company.

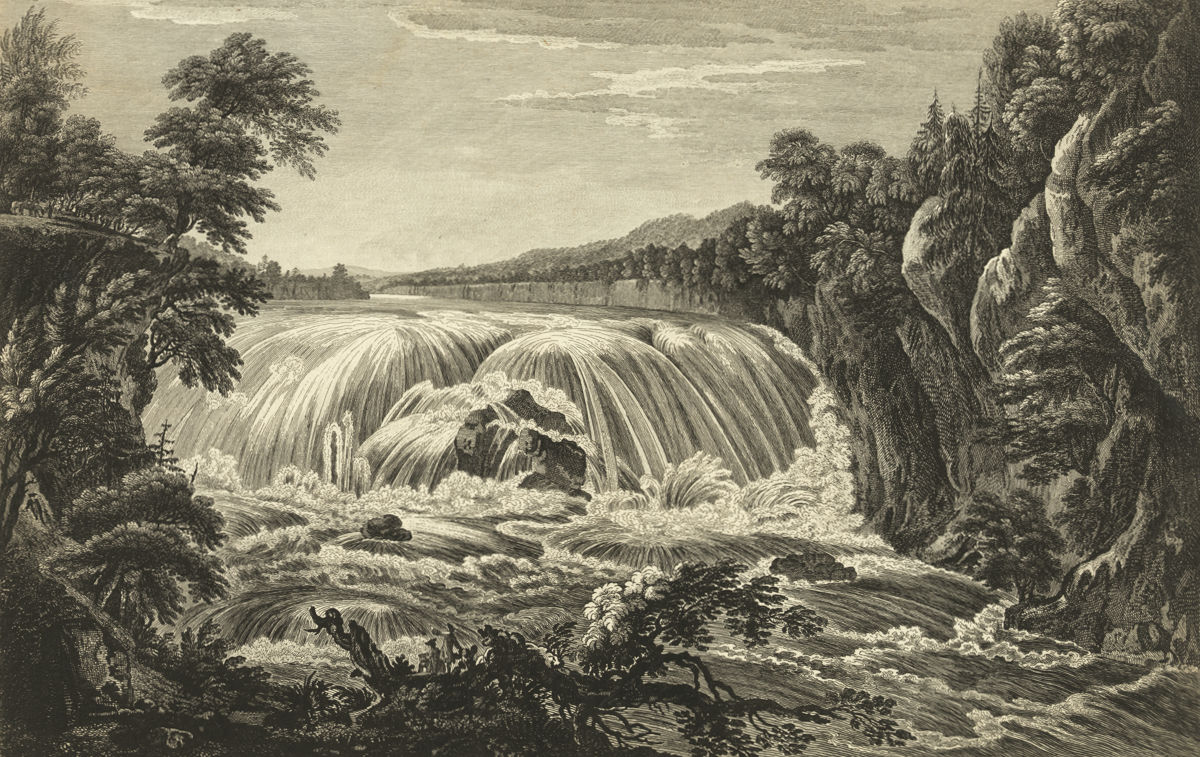

A private corporation formed to improve the waterways of central New York, the company was chartered by the state in 1792 to open routes from the Hudson River to points west.

The idea was not to build a single canal from the Hudson to Lake Erie, or even to Lake Ontario. At the time, that would have been considered little short of madness. Instead, short canals would divert existing rivers around waterfalls and link them with other rivers and creeks, making them navigable to large boats.

The Mohawk River would be opened by removing boulders and building wing dams to eliminate its numerous rifts, or shallow rapids. Wood Creek, the timber-choked, serpentine link to Oneida Lake, would be cleared, straightened, and connected to the Mohawk. Further work on the Oswego, Seneca, and Onondaga (now Oneida) rivers would extend navigation to Lake Ontario and the Finger Lakes.

It was an ambitious plan. Legislators, recognizing this, granted the corporation a 15-year time frame to accomplish it.

But the planner’s reach far exceeded their – and their young country’s – grasp. The vast scale of the project, with work sites scattered across thousands of square miles of wilderness, combined with primitive technology and poor management, doomed it from the start.

The planners’ lack of practical experience didn’t help.

Elkanah Watson, an early and vocal canal proponent and one of the directors of the corporation, made no secret of this a few years later when he described “borrowing” ideas from a similar project on the Potomac River:

“Indeed we were so extremely deficient in a knowledge of the science of constructing locks and canals, that we found it expedient to send a committee of respectable mechanics, to examine the imperfect works then constructing on the Potowmac, for the purpose of gaining information,—we had no other resource but from books.”

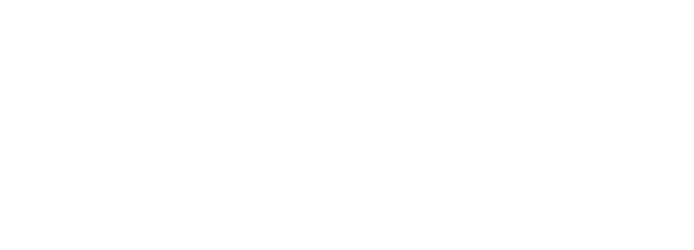

The Western Inland Lock Navigation Company operated until 1820, when it was purchased by the state and absorbed into the Erie Canal. Financially, it had barely survived and is considered by many to be a failure. Two of its primary objectives – opening the Oswego River to Lake Ontario and bypassing Cohoes Falls near Albany – were never seriously addressed.

Even so, much had been accomplished. In 1818, Watson wrote from Seneca Falls:

“In 1791, I came in a batteau from Schenectady to this place. . . . At that period they could only transport from one and a half, to two tons, in a flat boat, at an expense of from seventy-five to one hundred dollars a ton, from Schenectady to this place.

“By the completion of the works along the Mohawk River, Wood creek, and down Onondaga and up Seneca Rivers, in 1796, boats of a different construction, carrying from fifteen to sixteen tons, were introduced, and the price of transportation was reduced to about thirty-two dollars per ton, from Schenectady to the Seneca falls, and half that sum on returned cargoes.”

Later planners of the Erie Canal learned three important lessons from the failure of the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company. First, the economic benefit of constructing a water route from the eastern seaboard to the interior could potentially far outweigh the cost. Second, the idea of digging an artificial channel across New York state – crazy as that seemed – was the only way this could be accomplished. Finally, the scale of such a project exceeded the capacity of private enterprise and meant it would have to be organized by the state.

The elusive Durham

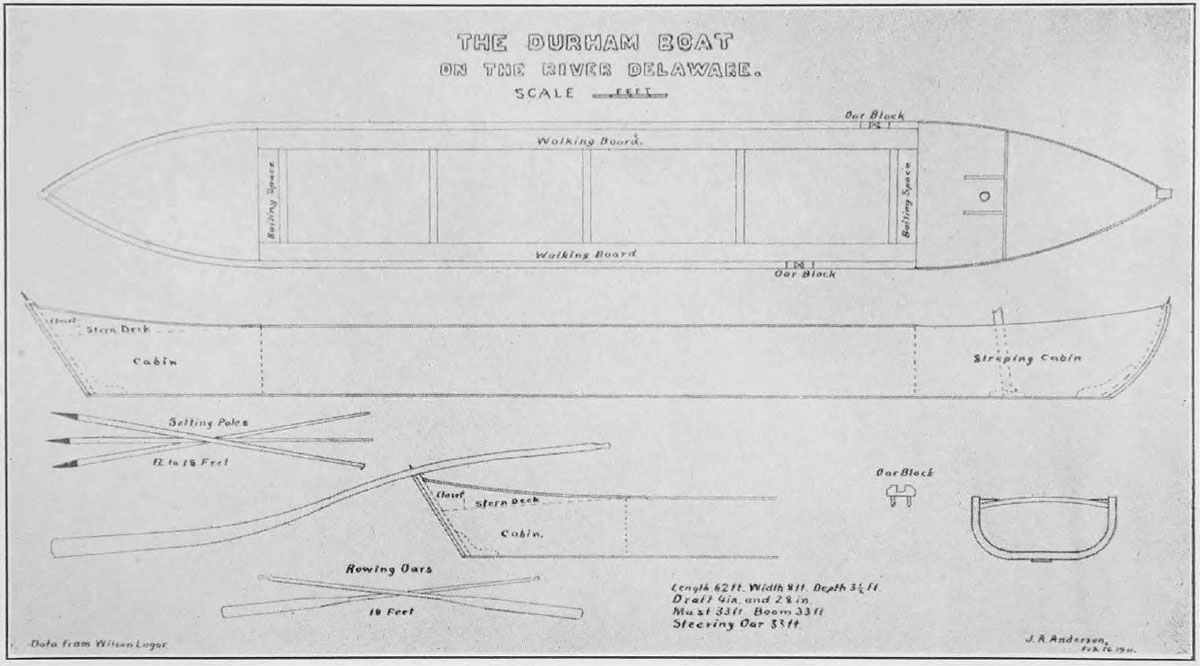

The “boats of a different construction” that Watson mentioned were almost certainly Durham boats. These narrow craft, about 60 feet long and pointed on both ends, had been used since the early 18th century to haul grain and iron ore on the Delaware River. Fully loaded, a Durham boat could carry from 15 to 20 tons of cargo, and its shallow draft and flat bottom made it perfect for navigation on swift-flowing rivers.

Famously, Durham boats were used by George Washington to ferry his troops across the Delaware on their way to Trenton, and victory, in 1776.

By the late 18th century, Durham boats were plying the Susquehanna and Mohawk rivers in Pennsylvania and New York, the St. Lawrence River in Canada, and even the Fox River in modern-day Wisconsin.

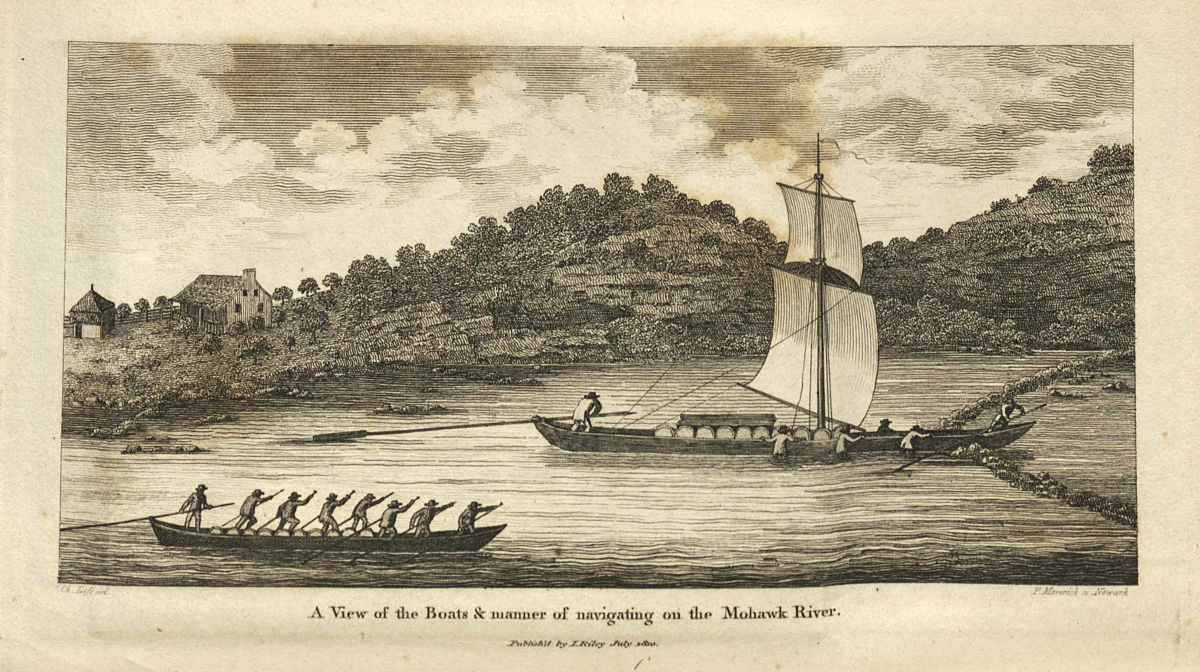

Despite regional variations, the boats all shared the same basic design. In deep water they could be powered by oars or sails – though the lack of a keel made that last bit tricky. In shallow water they were driven forward by men who walked the length of the boat – two or three on each side – while bracing themselves against long, iron-tipped poles set into the riverbed.

In 1888, historians in Wisconsin interviewed Alexis Clermont, who had been born in 1808 and, in his early 20s, joined the crew of a Durham boat:

“There were generally seven men of us – six poles and a steersman; sometimes there was a cook, but the usual custom was to have a cook for a fleet of three boats. Traders were in the habit of running such a fleet; for when we came to rapids, the three crews together made up a crew big enough to take the boats and their lading through with ease. Each boat had a captain who was steersman. Durham boats were from sixty to seventy feet long, and carried from twelve to sixteen tons.”

Similar accounts are scattered throughout the historical record. We know that the boats often set out in fleets of 25 or more; in all probability, thousands of Durham boats were in service at any one time, hauling raw materials like potash, grain, and iron ore downstream, and finished goods back into the interior. For good reason, the Durham boat has been called the semi-tractor trailer of early America.

But the commencement of the canal era, and later the arrival of the railroad, quickly made the Durham boat obsolete. This once-ubiquitous watercraft was gone by the Civil War, without leaving a trace.

For a while, though, Mohawk River Durham boats and Erie Canal boats would have co-existed, with Durham boats carrying on as before on the river while newfangled packets, freighters and line boats crowded into the new canal. This would have been particularly true in 1825, the date of the scene I’m working on, when the canal was not yet open to through traffic. So I’d really like to include a Durham boat or two on the river.

But what did they look like? How were they built? We are left with a few fragmentary descriptions and a couple of contemporary images. The best, created by New York engraver Peter Maverick and reproduced in Christian Schultz’s “Travels on an Inland Voyage,” shows a crew, waist-deep in the Mohawk River, struggling to guide their boat through the narrow opening of a wing dam.

That 1810 engraving might have been our last eyewitness view of a Mohawk River Durham boat.

If not for the fact that one was discovered on the floor of Oneida Lake two centuries later.

But that will have to wait for the next post.