“Before me the stupendous prospect charms the eye. Forty feet from bank to bank the canal spreads. Its depth of four feet can support the mightiest bottom afloat. The hand-built towpath is three hundred and sixty-five miles long. As for the traffic, surely not all the argosies of Greece could equal this spectacle. There are lineboats, packet boats, ballheads, Durhams, gala boats, counter-sterns, toothpick scows, dugouts, arks, flats and periaugers, and always the slow rafts, all transporting such cargoes as were never before conceived of.”—Samuel Hopkins Adams, Canal Bride

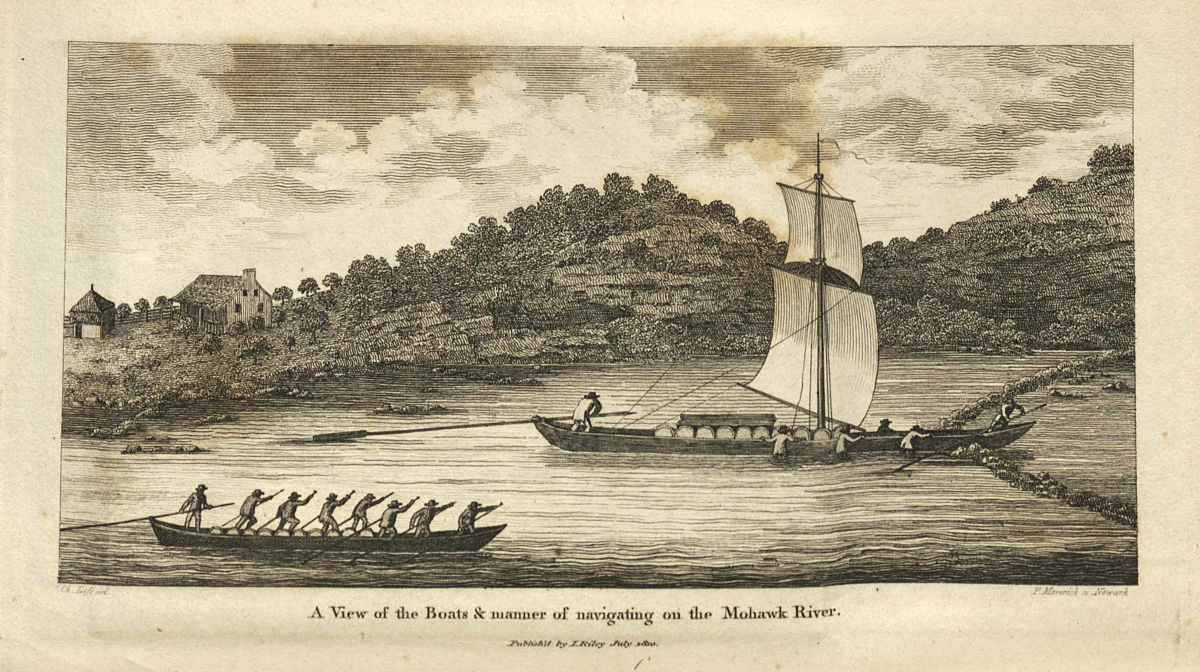

From the very beginning, as soon as individual sections were finished and opened, the Erie Canal became jammed with all sorts of vessels. Many were barely seaworthy, rough rafts poled along by owners eager to cash in on the novelty and ease of this new mode of conveyance. Because the canal was built at taxpayer expense, it belonged to every citizen. Anyone who could pony up the toll could use it. And they did.

As with many things concerning the early Erie Canal, details of the boats first used on it are now obscure. Mostly we are left with vague, second-hand accounts that don’t go into much detail.

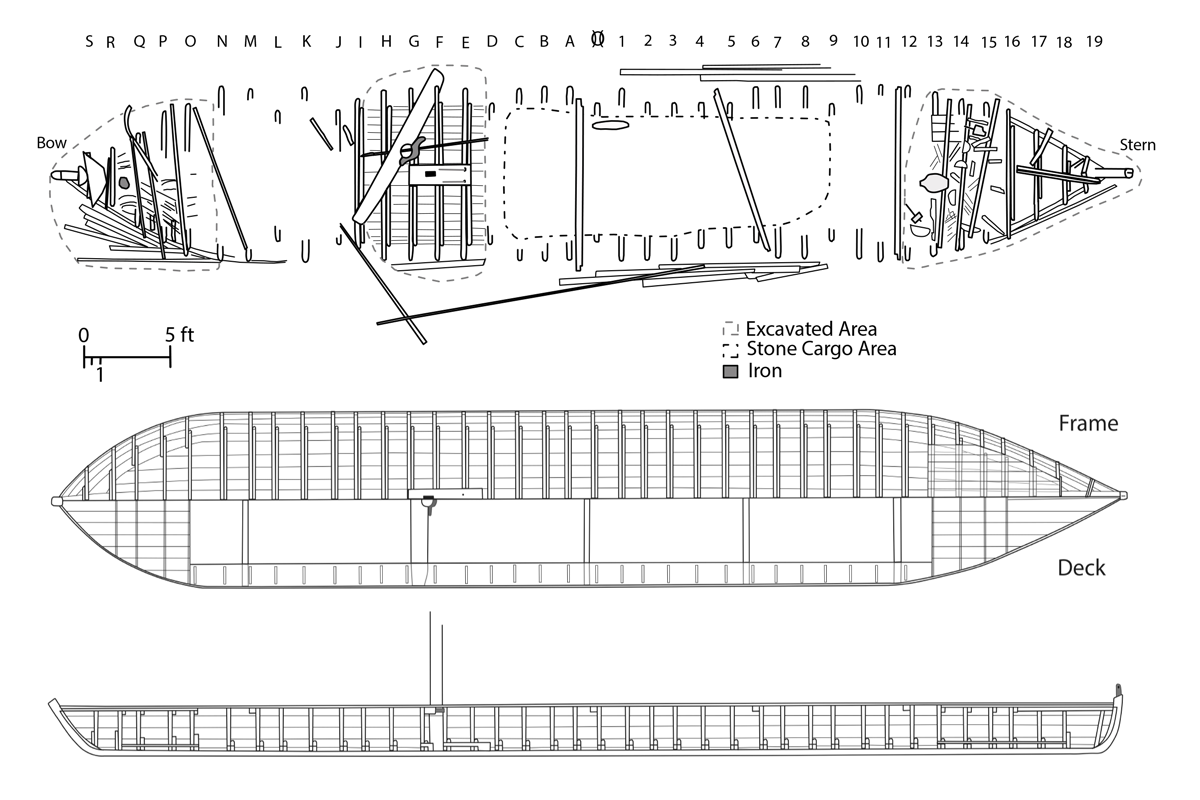

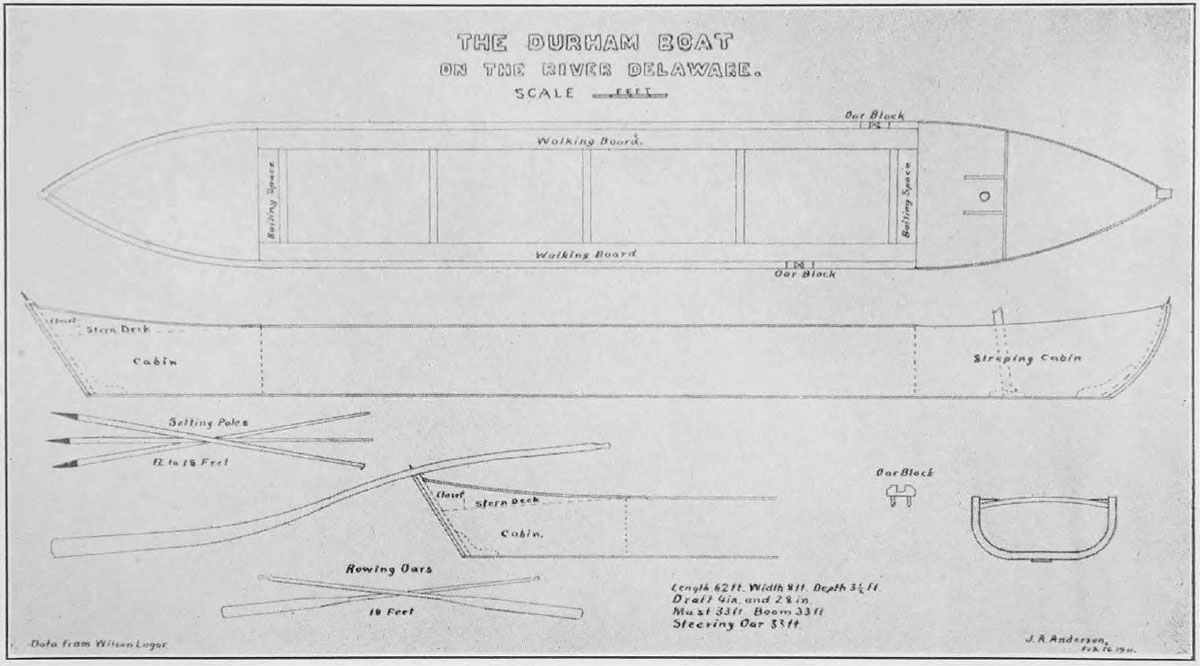

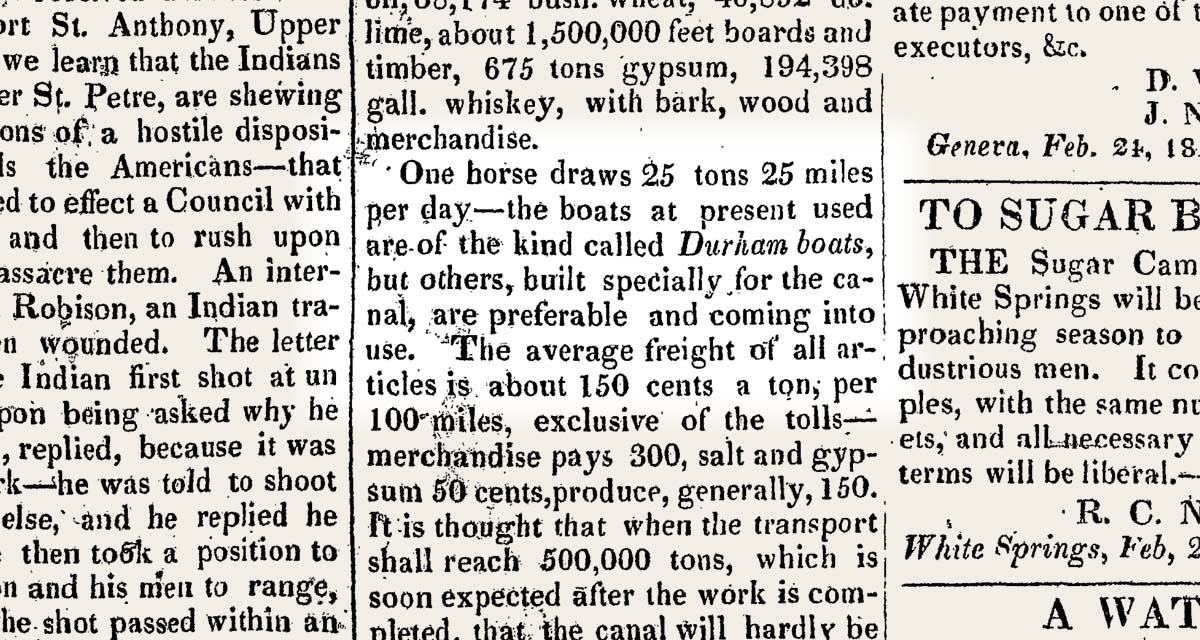

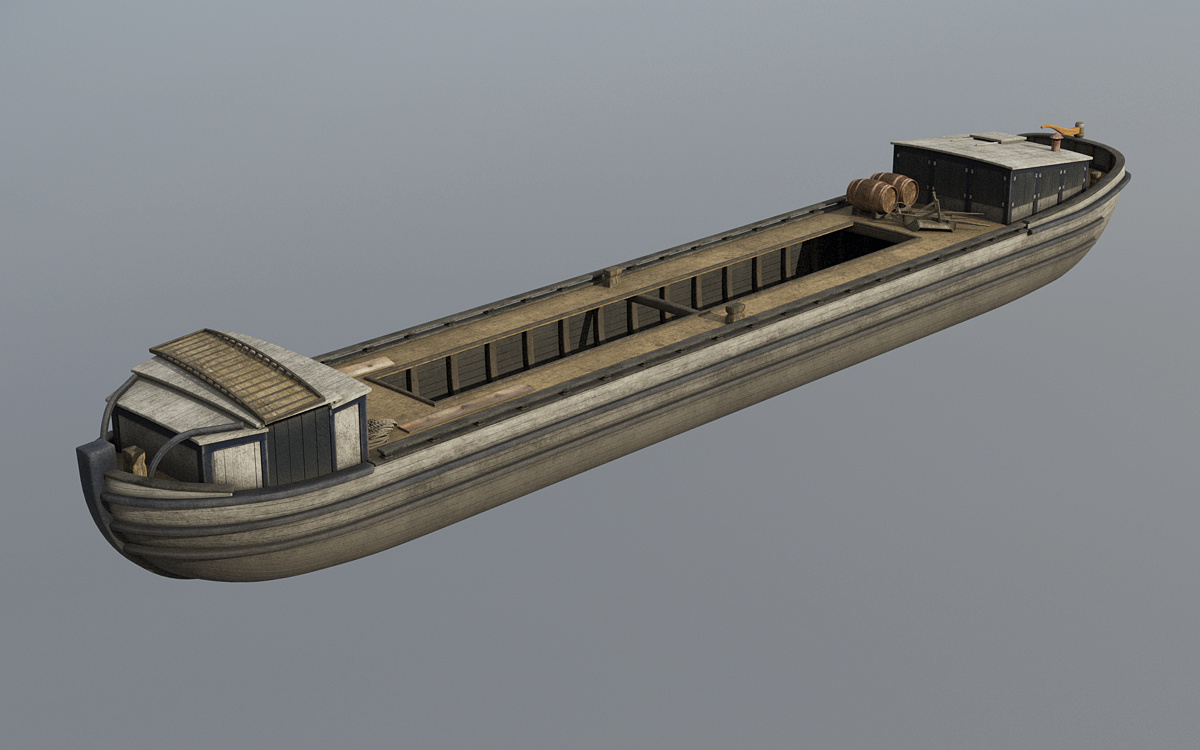

These report that early freighters were small, 60 or 70 feet long, 7 feet in the beam, and could haul about 30 tons of cargo. By 1830 boats reached their maximum size, 75 feet long, about 14 feet in the beam, and could carry up to 75 tons.

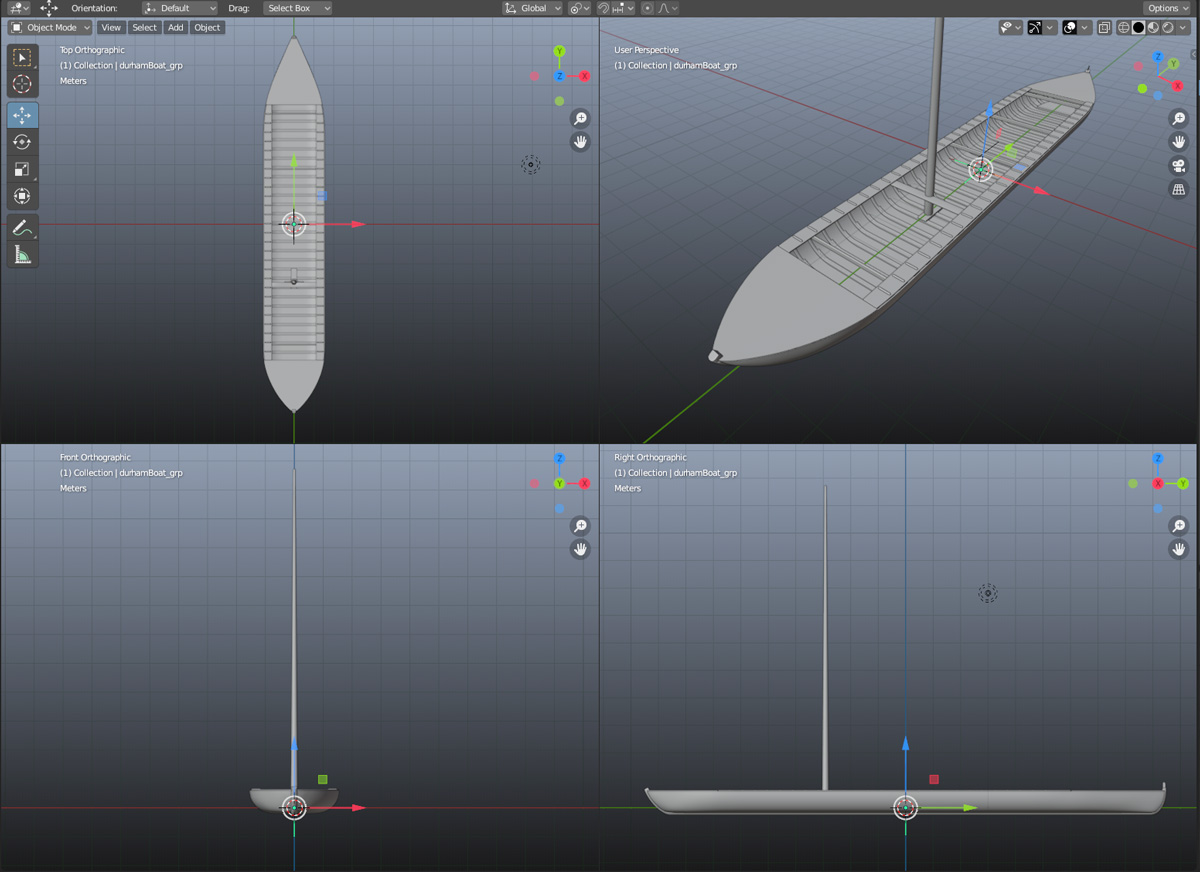

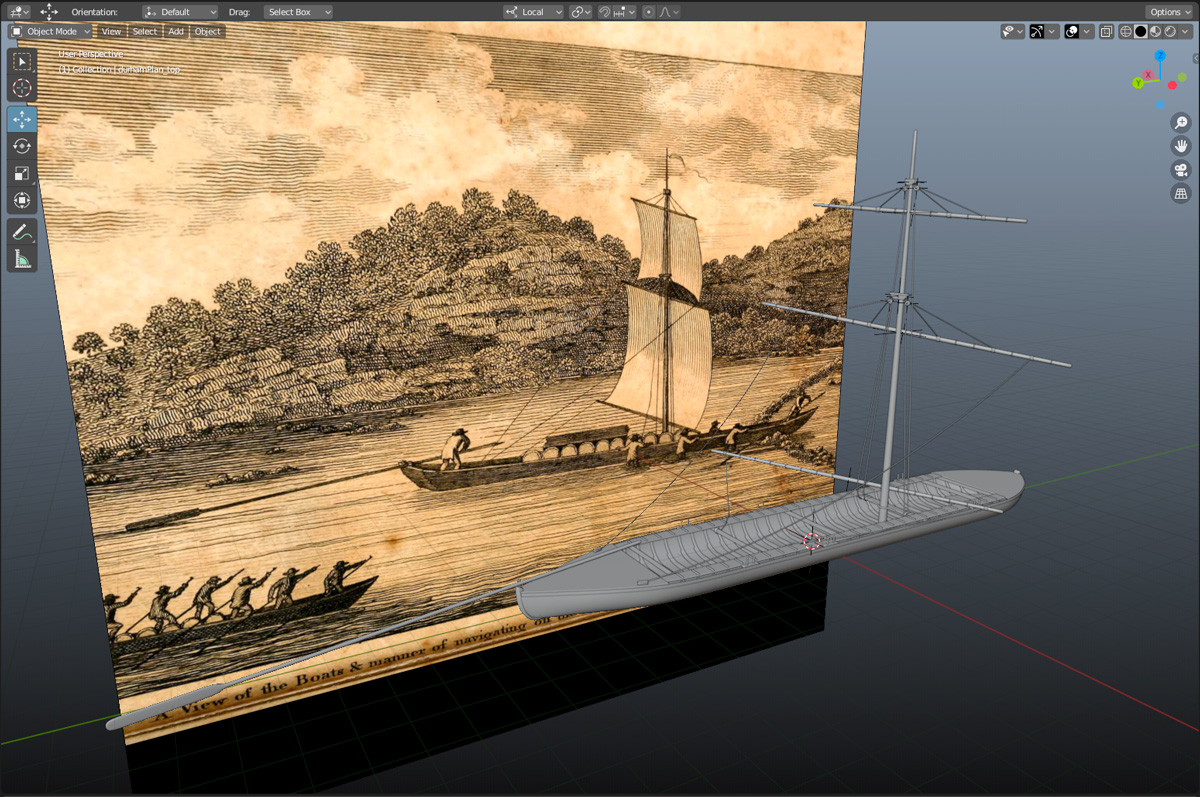

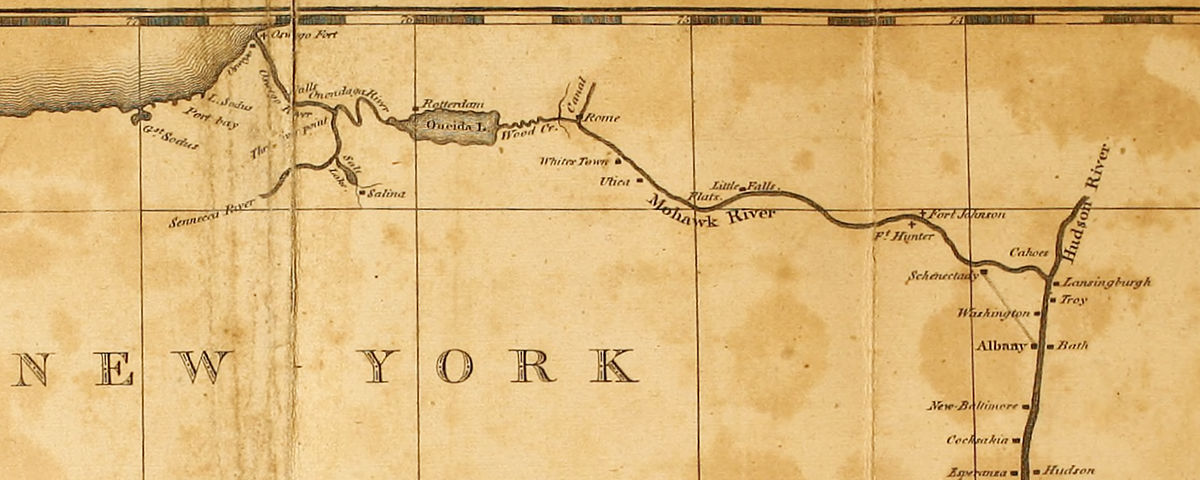

The first set of dimensions are similar to those of a Durham boat, which suggests that some of those Mohawk River watercraft were being diverted to the canal to help fill a sudden demand for boats. Contemporary newspaper reports confirm this.

At the time boatbuilding was a traditional occupation in which the master builders did not work from blueprints but from experience and memory. That sort of industry does not turn on a dime. It may be that existing boatyards continued to turn out boats modeled on the Durham long after the first sections of the canal were opened.

New boatyards eager to cash in soon sprang up, particularly in new canal boomtowns such as Utica, Rochester, and Buffalo. They would have built boats designed for maximum profit, as large as the canal’s 15-by-90-foot lock chambers would allow. I suspect that 14-by-75-foot boats would have been common well before 1830.

The canal commissioners allude to this in their 1825 report. “Two boats cannot pass each other upon any of the aqueducts,” they wrote, “and the canals being but 40 feet wide on the surface, and 28 at the bottom, and the boats 14 feet wide, only two can pass each other on the canal . . .”

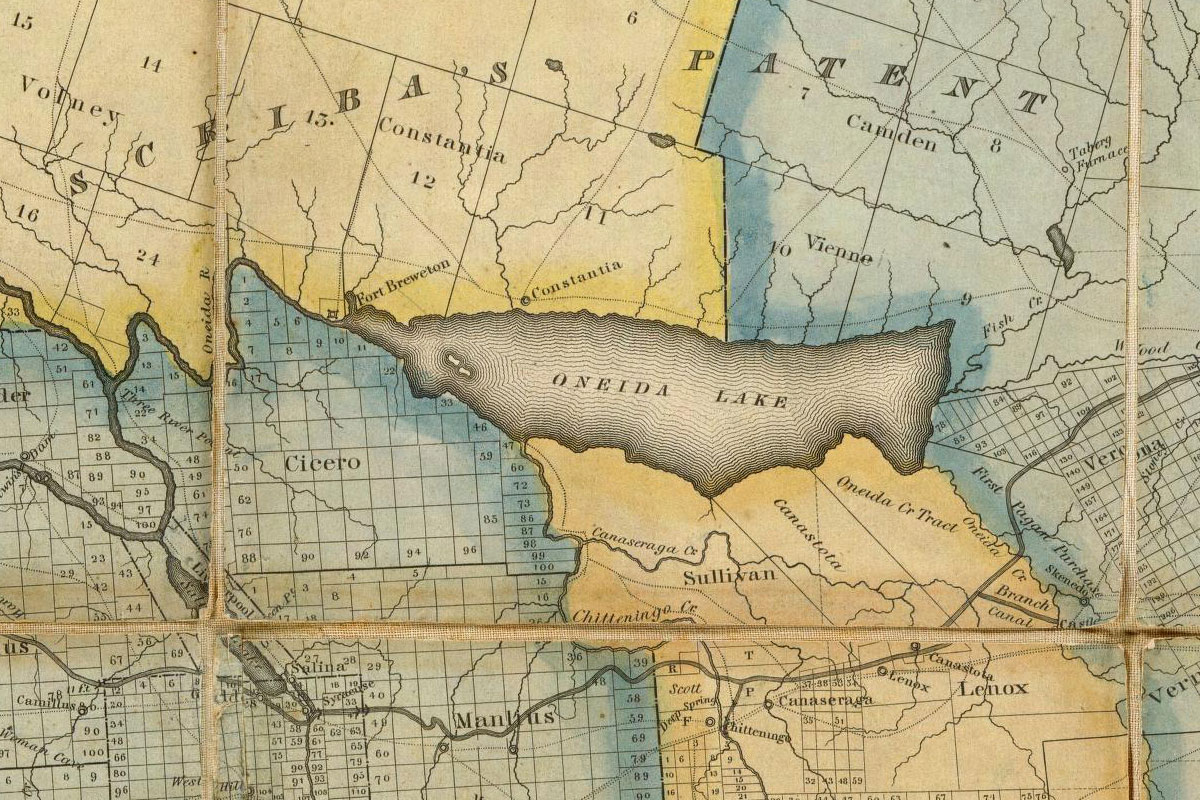

Finger Lakes time capsule

Fortunately for us, working Erie Canal boats have been preserved at the bottom of a lake in central New York.

Seneca Lake, one of New York’s Finger Lakes, in 1828 was connected to the Erie Canal by the Cayuga and Seneca Canal. In 1834 a second lateral canal connected Watkins Glen, at the lake’s southern tip, to the Chemung River at Elmira. Canal boats, pulled by horse or mule teams along the laterals, were towed by steamships across the lake. The boats mostly carried Pennsylvania coal, but the Elmira, Corning, and Buffalo Line also advertised a weekly passenger run from Elmira to Buffalo.

Canal boats would be towed across the lake until 1878, when the Chemung Canal was abandoned. Not all of them made it. Seneca Lake, very deep and subject to sudden squalls, would claim a few.

An underwater survey using side-scan and multibeam sonar would begin to find them in 2018 and 2019. The Seneca Lake Archaeological & Bathymetric Survey was led by researchers from the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum with the support of New York state and several private organizations, and included members of the team that had discovered an early 19th-century Durham boat in Oneida Lake.

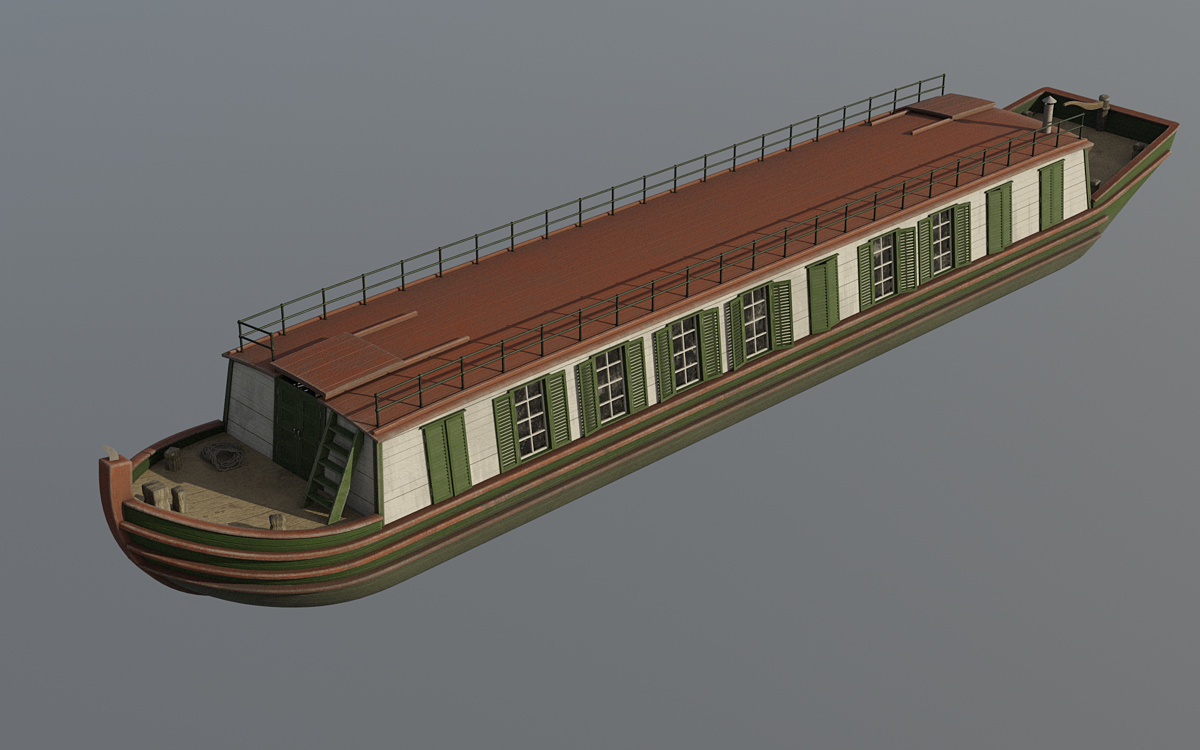

Promising targets were visited and photographed by an underwater, remotely operated vehicle. The result is a catalog of 19th-century canal vessels, from scows and freighters to, incredibly, what looks to be a passenger packet. (You can support one of the survey sponsors, the Finger Lakes Boating Museum, by purchasing a printed copy of the survey report from their online shop.) Allowing for the fact that all of the wrecks are encrusted with invasive quagga mussels, many are in remarkable condition.

Several of the wrecks have been identified as original Erie Canal-era boats. In the late 19th century the average lifespan of a canal boat was 10 years. If this held true earlier in the century, then some of these boats, which date from the mid-1830s, may have been built in the 1820s.

One of the wrecks was a scow, a open, square-ended design that was outlawed in the 1840s because of the damage its sharp corners caused to canal structures and other boats. But the hulls of the other original Erie-era wrecks have more graceful lines.

These shapes seem to differ from what would come later. The boxy lakers of the late 19th century and industrial steel barges of the 20th were, above all, utilitarian. But these were boats. It’s almost as if their builders, faced with the new challenge of crafting vessels for the placid waters of the Erie Canal, still had the unpredictable Mohawk River very much in mind.

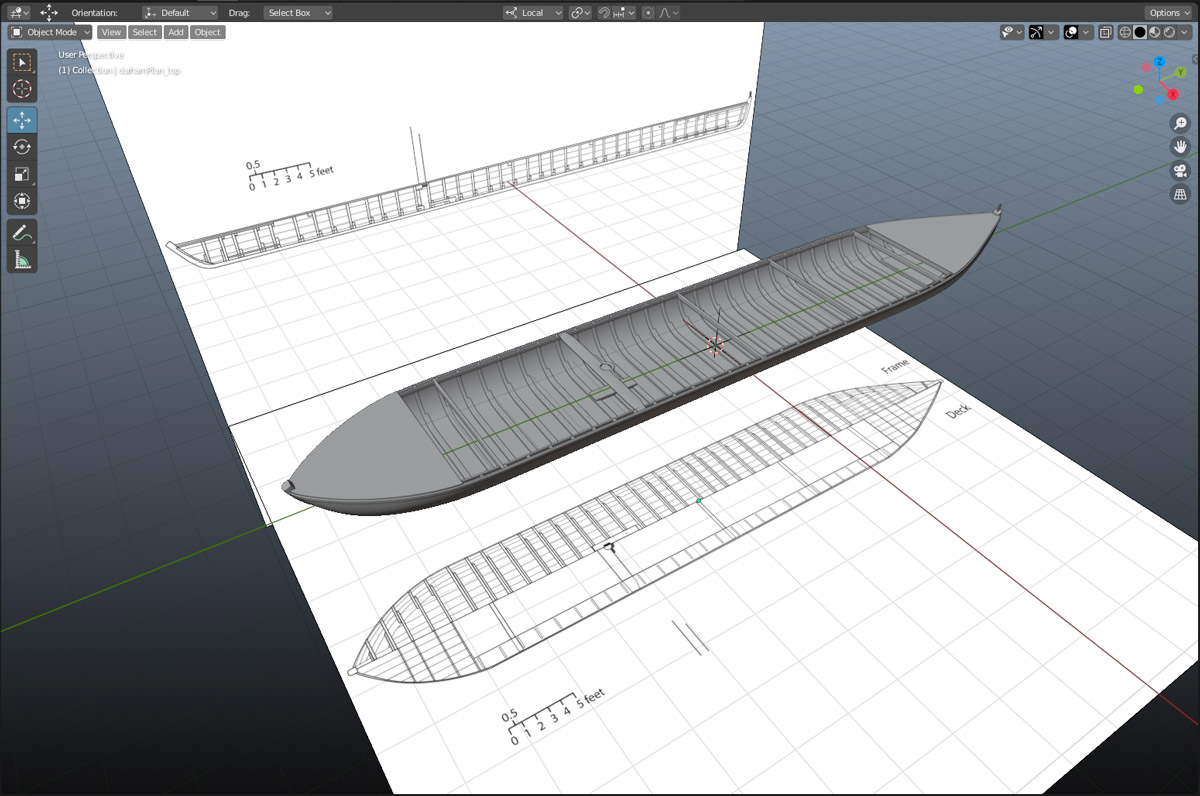

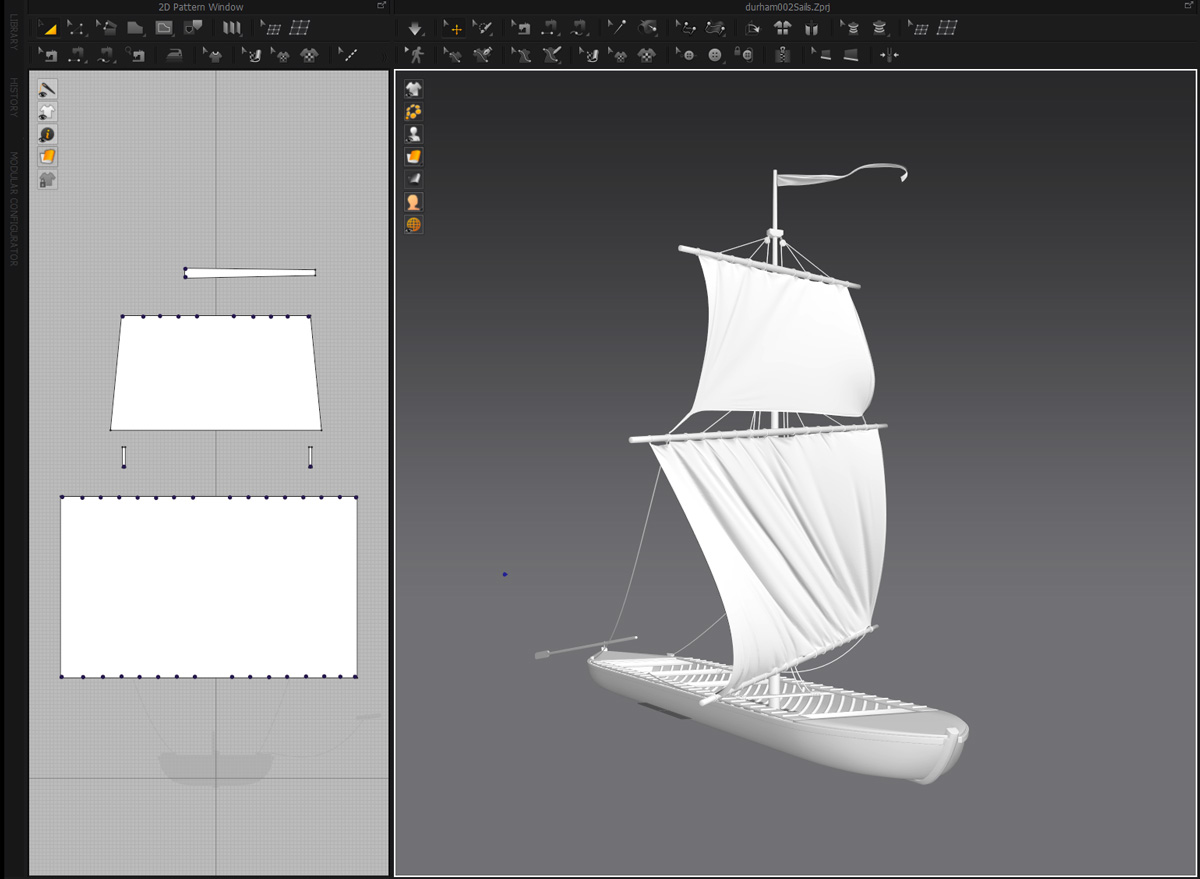

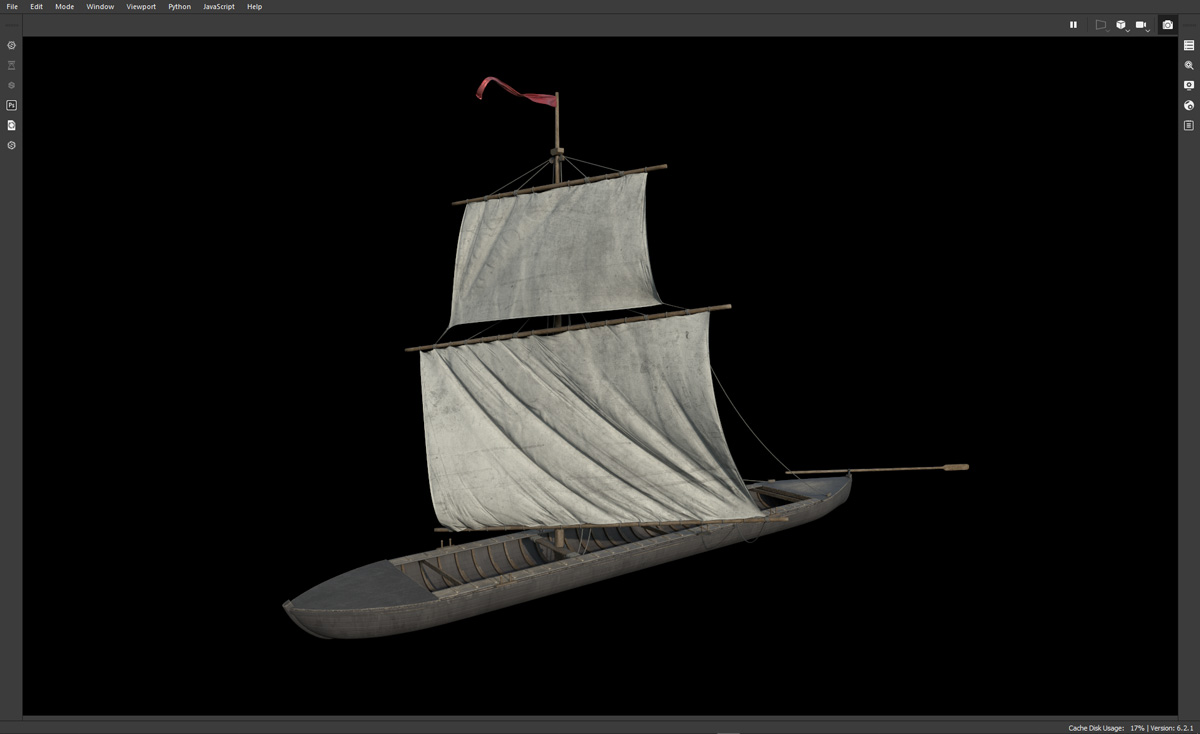

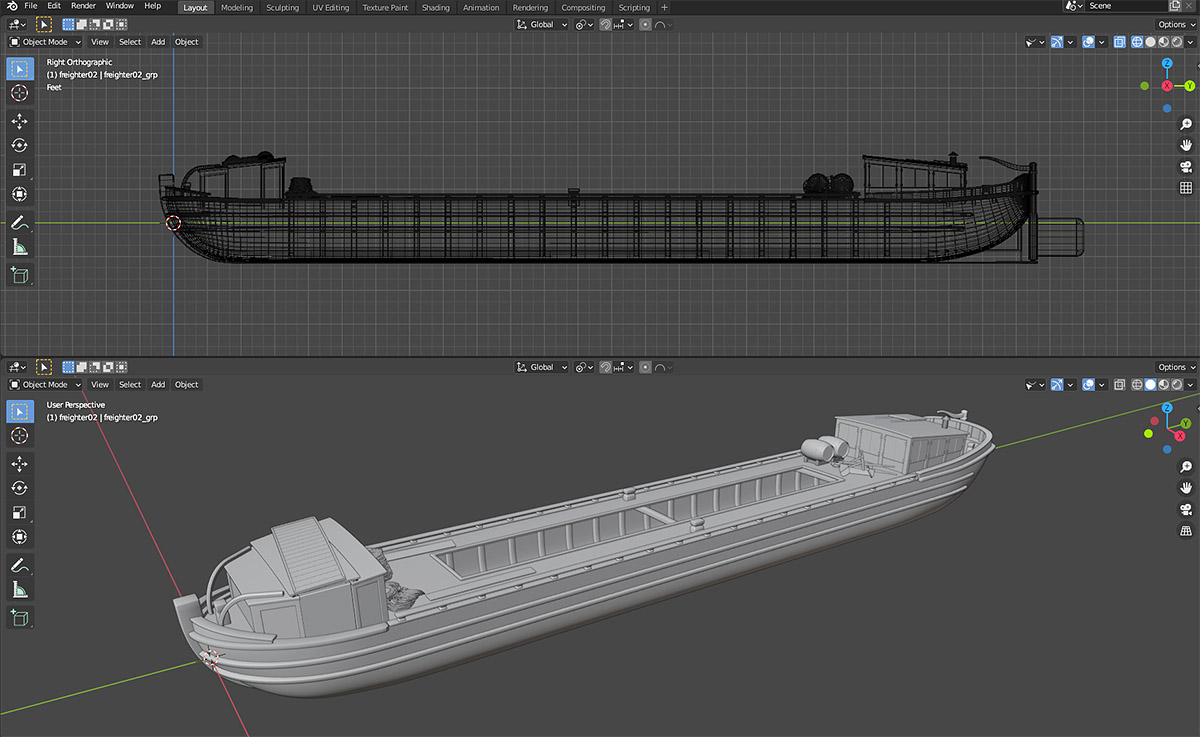

The expanded fleet of models will eventually find its way into new scenes as they are created. Next up will be adding some less-conventional vessels, like the log rafts (which were actually very common) used to transport timber to market, a line boat, and maybe even a periauger.

Without a doubt, the early canal years featured a more diverse and colorful array of watercraft than we can imagine today. For the wide-eyed Yorkers along the canal route, astounded by the sight of boats floating one after another through the landscape, it really must have been quite a spectacle.