The most striking objects in George Catlin’s lithograph of the Deep Cut excavation are, of course, the horse-powered cranes. Arranged on each side of the cut, the repeating, angular shapes make a dramatic pattern against the sky.

The lithograph, along with additional scenes of the canal by Catlin and other artists, was printed in Cadwallader Colden’s Memoir, published in 1825 to commemorate the opening of the canal. The image and its descriptive text, included in an appendix, are our primary source of information about the machines.

“The cranes,” the writer reports, “are an ingenious application of mechanics to a horse power, enabling him to raise a ton weight or more from the bottom of the Canal, and discharge it in huge piles at a distance of sixty or seventy feet from the excavation, and fifty feet above its banks. They were generally set at regular distances from each other, (sixty or seventy feet) and fifteen or twenty feet from the Canal, allowing the extremity of their gibs to describe about to the middle of the chasm.”

After spending another paragraph or two describing how they worked, the writer adds (with some degree of understatement) that the cranes, “when in full operation for three miles in length, and the work progressing under the hands of fifteen hundred men, under a continual cloud of smoke, and almost incessant explosion of rocks, produced a novel and interesting scene.”

The machines were the brainchild of Lockport contractor Orange Hezekiah Dibble. Aside from the text in the Memoir, detailed information about his invention is hard to come by.

The canal commissioners’ annual reports to the state legislature – generally expansive when describing new technology, especially when it was inspired by the canal – are silent about the cranes, though Orange Dibble is listed as a contractor.

There is no patent application or drawing. Any that existed would have been destroyed in the fire that swept through the patent office in December 1836. But we know that a patent was issued. A list published in 1840 includes one for an “Earth, removing” machine awarded to Orange H. Dibble of Niagara County, N.Y. on February 20, 1824.

Two months later – April 1824 – this notice appeared in the Lewiston Niagara Sentinel:

“Fatal accident — David Gilroy, a laborer on the canal, was killed near this village on Friday last. He was engaged with a number more in excavating rock with a machine which is worked by horsepower. The box appertaining to the machine had been filled with stone amounting probably to 1,000 pounds, when after being raised to the height of 30 feet directly over the head of the unfortunate man the chain by which it was suspended broke and the box and contents fell upon him and killed him instantly.”

Apart from reminding us just how very dangerous canal work could be, this brief item confirms that at least one of Dibble’s machines was on the line early in the 1824 construction season.

Finally, there is one more very reliable source.

“Of the crane I enclose a figure”

Increase Allen Lapham was born in 1811 to Seneca and Rachel Allen Lapham of Palmyra, New York – a backwoods village that later would become a stop on the Erie Canal. His father was a contractor who specialized in canal construction. His family followed work as it became available and was constantly on the move.

In 1818 they relocated to the Schuylkill River in southeastern Pennsylvania. Two years later they returned to the town of Galen in western New York, just a few miles away from the Erie Canal, then under construction. In 1822 they moved on to Rochester. Increase and his older brother, Darius, covered the 30-mile distance on foot, driving “a cow & calf,” as Increase later noted in his diary. In Rochester, Seneca Lapham worked on the aqueduct that would carry the canal over the Genesee River.

In 1824 the family was in Lockport, where Seneca built lock gates and bridges. Young Increase labored on the canal as well, writing that he “cut stone for the locks sometimes & earned $1 per day.” But he and his brother were soon moving up. “We have got acquainted with Mr. Alfred Barret the Engineer of the canal & Darius got employment under him — Soon after I was also employed at $10 pr month & $.50 per day for subsistence.”

Increase was extremely bright and quickly began to soak up the basics of surveying and canal engineering. He was also observant and took note of everything having to do with canal construction on the Mountain Ridge, including Orange Dibble’s cranes.

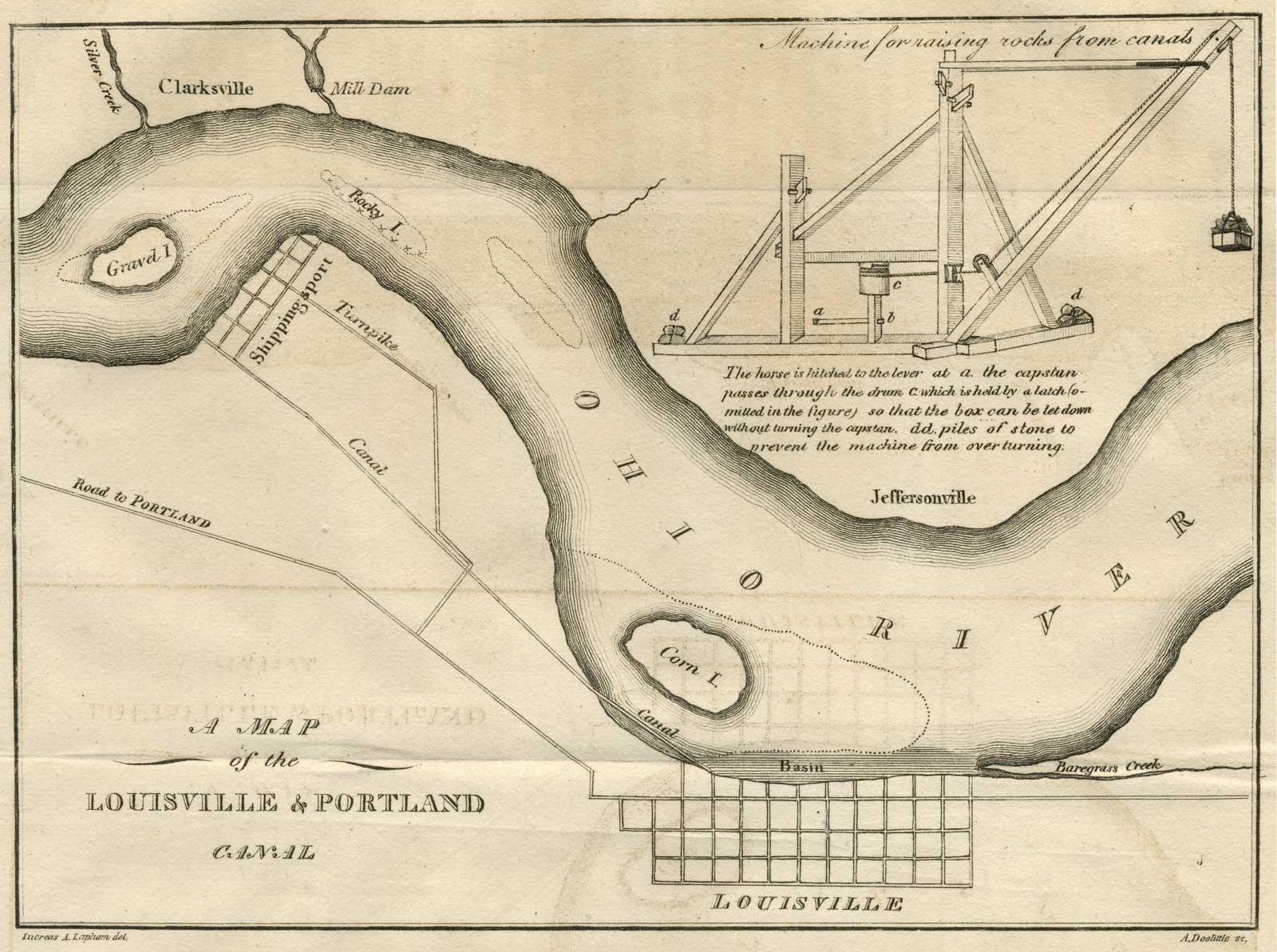

By 1827 the family had moved yet again, this time to Shippingport, Kentucky, where the Louisville and Portland Canal was being constructed around the Falls of the Ohio River. It wasn’t long before Increase was handling much of the company’s bookkeeping.

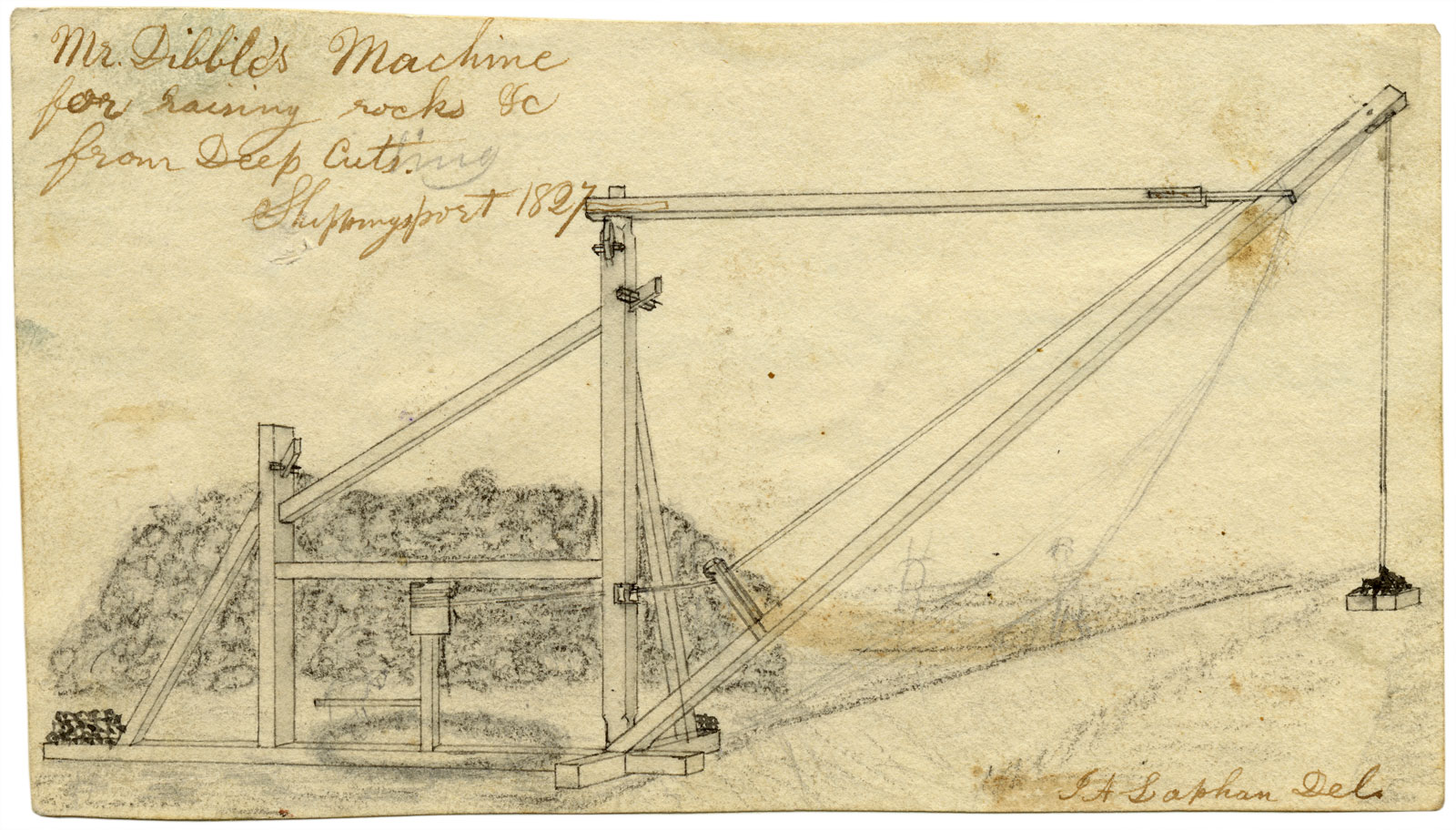

The Louisville canal included a difficult rock cut much like the one at Lockport. Cranes like those used on the Mountain Ridge were being built and pressed into service. Sixteen-year-old Increase, now an assistant engineer and an accomplished draftsman, made a drawing of one of them. He sent the drawing, along with an article that he had written about the construction of the Louisville canal, to Professor Benjamin Silliman of Yale University for publication in the American Journal of Science and Arts.

“The excavation of rock is done by drilling, and blasting,” Increase wrote in the article, “and is afterwards removed from the canal, by the use of a crane of the same construction as those used on the mountain ridge in New York, invented by Mr. Orange Dibble. Of the crane I enclose a figure.”

Increase Lapham stayed with the Louisville canal until 1829. Eventually he made his way to Wisconsin, where he became a naturalist and cartographer. He died in 1875 and today is revered as the state’s first great scientist.

Orange H. Dibble continued to do contract work for a few more years and became postmaster of Buffalo, by then a boomtown because of the Erie Canal. Eventually he, like so many others, was swept up by the Gold Rush and moved his family west. He became one of the original pioneers of Grass Valley, California, and operated a sawmill in nearby Gold Flat. He figured prominently in the state’s Masonic organizations until his death in 1864.

George Catlin went on to fulfill his dream of painting Native Americans, and spent most of the 1830s traveling throughout the American West. Later he took his “Indian Gallery” on tour in the eastern U.S. and Europe, where he turned out to be as much of a showman as an artist. After returning to the states he was forced to sell the gallery to pay off personal debts. Today the collection – more than 600 works – is part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Catlin died in 1872.

The cranes themselves, thanks to Catlin, have achieved a permanent place in our imagination and the mythos of the canal’s construction.

At the time, they were a rough-and-ready solution to a simple problem: How to get rid of the broken rock from the bottom of the ever-deepening Deep Cut. Lockport was an isolated outpost surrounded by forests and swamps. The pioneer contractors working there had to make do with local materials, and timber was plentiful.

The resulting machines were primitive and dangerous, but apparently they did the job. It’s been said that they speeded up completion of the Deep Cut and the canal. Perhaps. But by the time they appeared on the line in 1824, perhaps late 1823, much of the excavation was already done. Maybe the problem wasn’t one of time, but space: Once the channel reached a certain depth, wheelbarrows and ramps became impractical and another solution was called for.

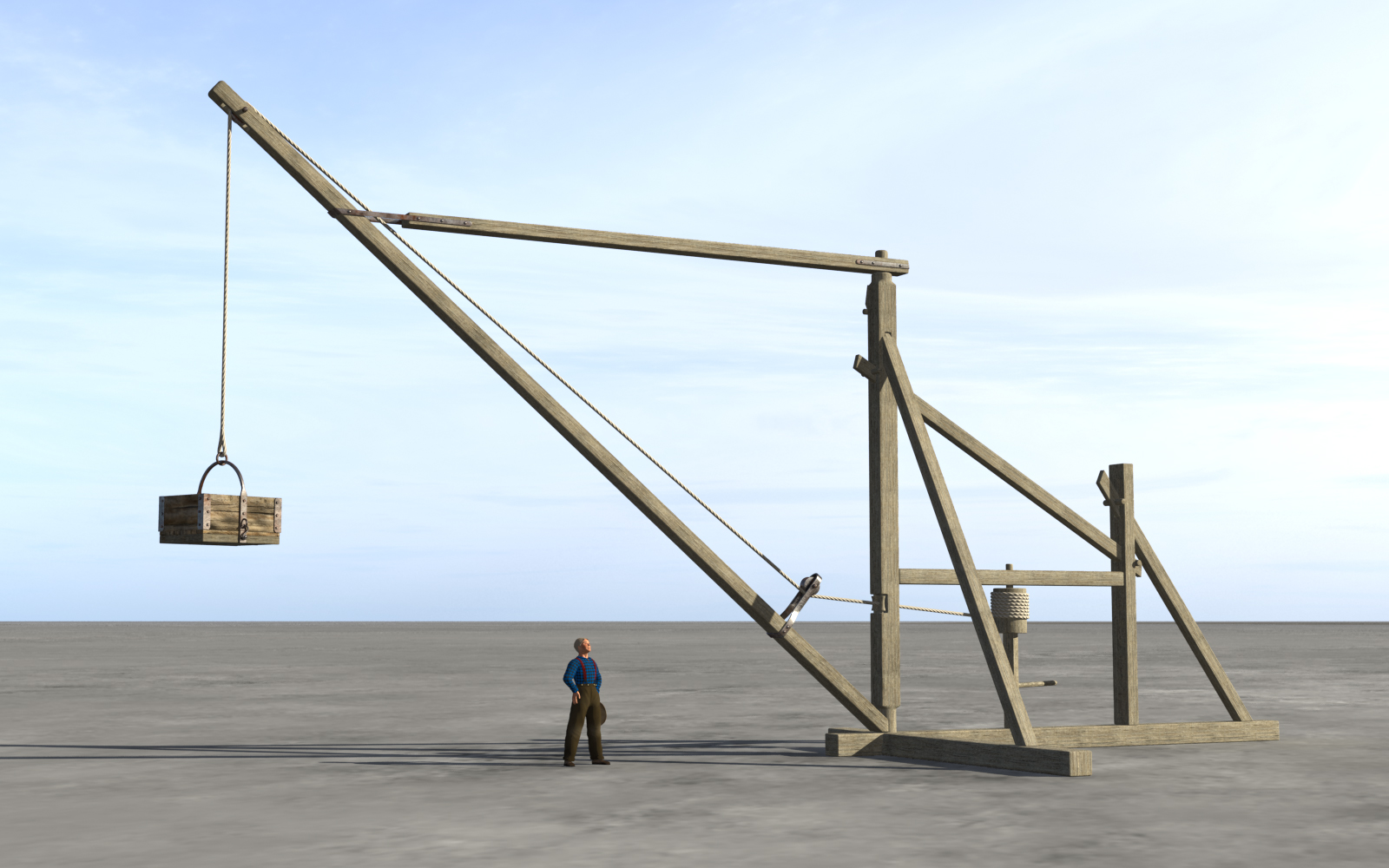

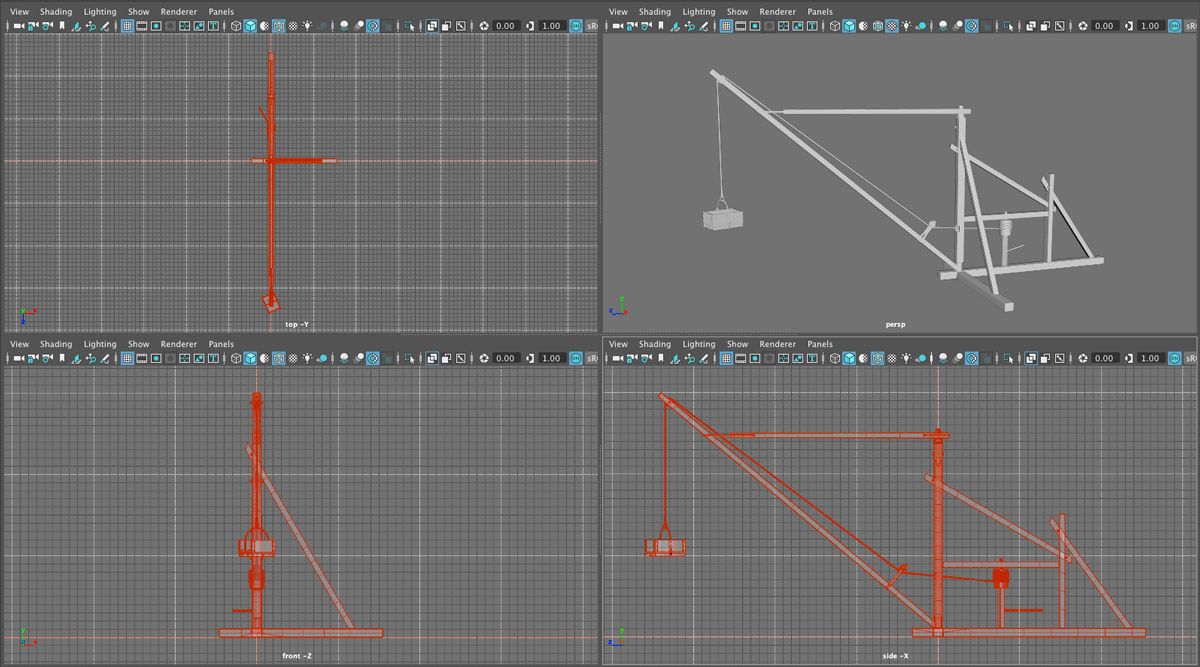

Modeling the machine

Catlin’s cranes are the work of an artist: fleeting, energetic and alive, they nevertheless contain very little practical detail. Which is why I’m so grateful to have found Lapham’s drawing, which was the work of a budding engineer. All of the details that we need to know about the machine are there with one exception: scale.

The ghostly, pencilled human and horse figures in Lapham’s drawing give us some idea of how big the cranes were, but determining a reasonable scale still took some experimentation. The placement of the cranes at intervals of 65–70 feet – as specified in the Memoir – was one factor, as was the need to provide enough room for the piles of stones.

For now, I’ve settled on a machine that’s 30 feet high, with a mast of 25 feet and a horizontal reach of 34 feet. The diagonal jib is about 45 feet long. The contractors who built the machines would have been felling a forest of old-growth trees – sugar maple, beech, oak, ash, and elm – so obtaining beams this size should not have been a problem.

It’s a simple machine and the model comes together quickly. We’ll make many variations to insert along the cut in the scene. Final details – including horses to provide power and teams of workers – will be added once the cranes are all in place.