The Deep Cut was a man-made artifact that sliced across the landscape of western New York. At the time, many people saw it as a work of “art” that improved Nature for the benefit of all.

But even though Nature was “improved,” it wasn’t completely overcome. The waterlogged terrain that constantly threatened to flood the work, the dense forest, and most of all the layer upon layer of tough dolomite resisted the incursion and made life miserable for the engineers and workers struggling to execute the great work.

Little was spared in the effort. Great quantities of black powder and whiskey – and an untold number of lives – were consumed as the cut inched forward.

The result was a pre-industrial industrial landscape.

Orsamus Turner, an early settler and newspaper editor, recalled the scene in his Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase of Western New York:

“The dense forest between Lockport and Tonawanda creek looked as if a hurricane had passed through it, leaving a narrow belt of fallen timber, excavated stone and earth . . . The blasting of rocks was going on briskly, on that part of the canal located upon the village site; rocks were flying in all directions . . . and huge piles of stone lay upon both banks of the canal . . .”

This would have been 1822 as work was just beginning. The blasting and huge piles of stone would extend along the entire length of the cut as work continued through 1825.

Digging up the dimensions

As I began to put together the landscape for this scene, my first question was pretty basic: What were the dimensions of the cut?

Surviving records from the original construction period are sparse. We have the annual reports of the canal commissioners, letters from them and the supervising engineers, some early surveys, and some contracts and receipts. To the best of my knowledge there are no engineering plans as we understand them today.

This was art, after all, created by artisans. In the pre-industrial era masons and carpenters drew upon their visual imaginations and years of experience and not much else. Locks, dams, weirs, and so forth were built from memory or perhaps by referring to sketches that were quickly discarded. It was an effective way to work, and the structures that remain attest to the care and pride they took in it.

This soon changed. The industrial era – introduced to some extent by the canal itself – required bureaucracies, trained engineers, and armies of surveyors, clerks and draftsmen. As planning for the first canal enlargement began, they got to work.

The New York State Archives in Albany has several volumes of contracts and estimates, one of which was completed in the late 1830s for enlargement work along the Deep Cut. I’m grateful for the help provided by the archivists who tracked this down.

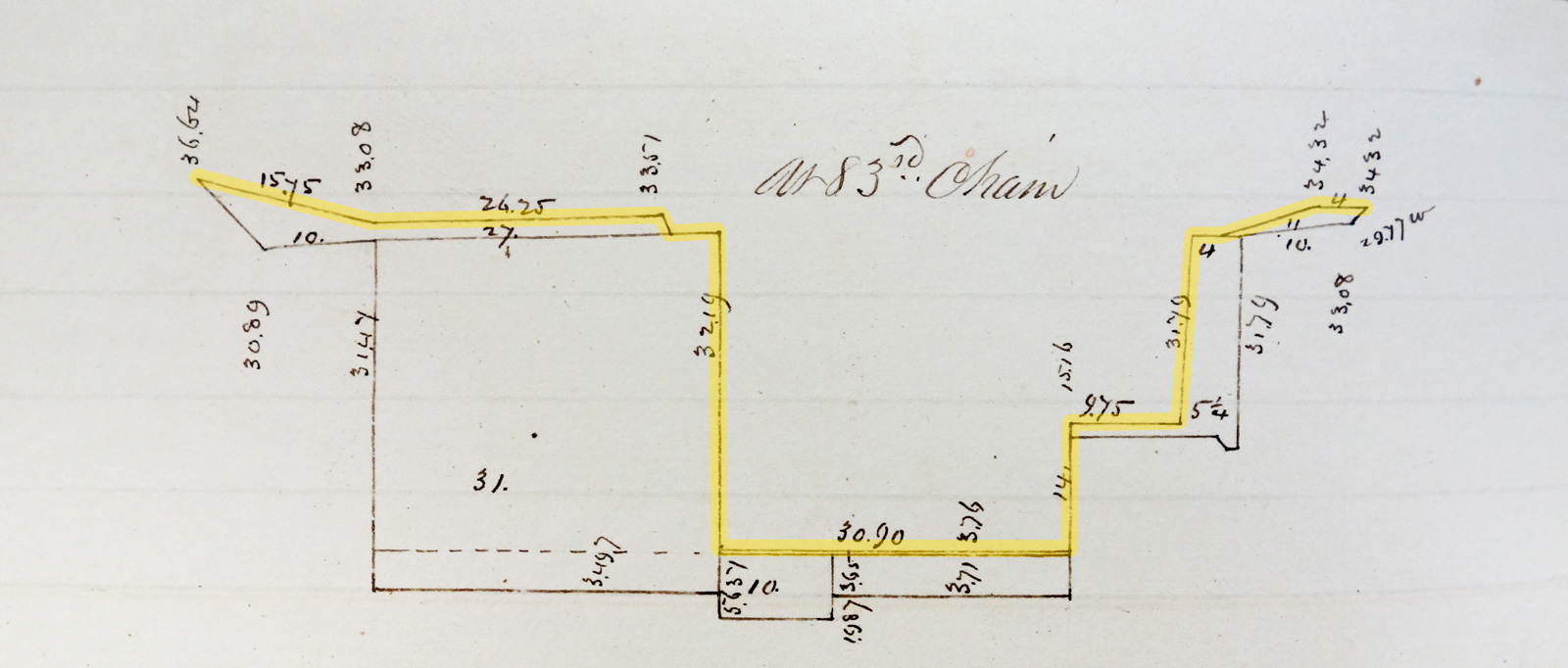

The volume contains hundreds of precise cross sections used to calculate the exact amount of soil and rock to be removed for the enlargement. To make them, surveyors measured the prism at intervals of 66 feet (one chain) all the way from Lockport to Tonawanda Creek.

The measurements confirm the maximum depth of the original profile, about 32 feet, mentioned in the canal commissioners’ annual reports. They also include the channel width and the size of the ledge for the towpath. The channel is narrow, about 31 feet, just wide enough to allow two canal boats to pass. The towpath is 10–12 feet wide, just wide enough to allow two teams of mules or horses to pass.

Apparently, the original engineers did not want to blast a single unnecessary cubic yard of rock.

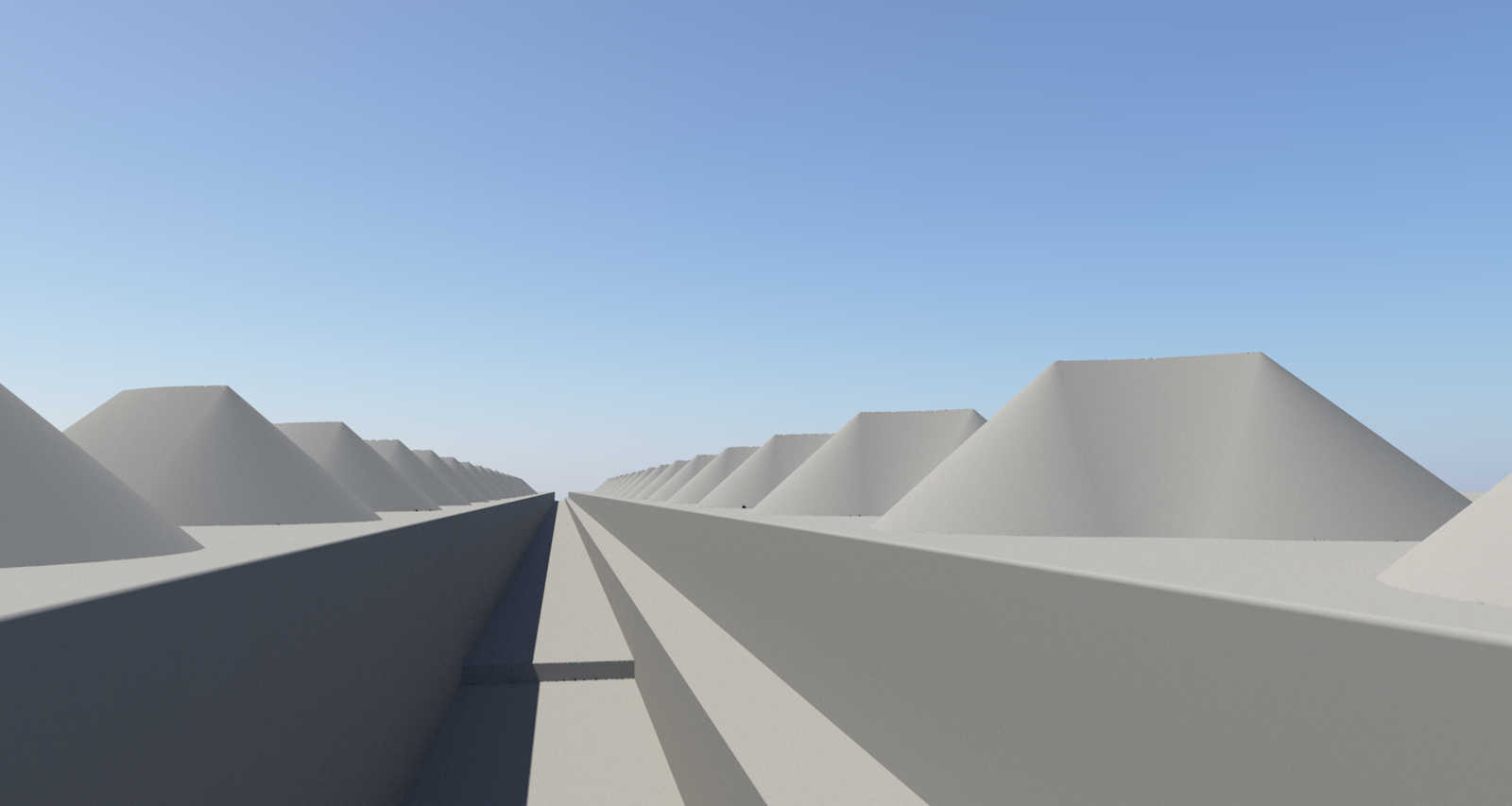

Constructing the surface

The depth of the cut, the vertical walls, and the number of lateral (sideways) displacements make this a difficult landscape to model. After a couple of false starts I used an approach suggested by Ulco Glimmerveen on the Terragen user forum. This approach uses a few large primitive shapes – three cubes and a plane – to set up the basic surface, along with the rock pile shapes described in an earlier post.

The rock walls required more experimentation. Excavated dolomite resembles shale but has thicker layers. Later historical photos (like the one included at the top of this post) were a big help here. (Photos of the original excavation, of course, are nonexistent – photography hadn’t been invented yet.)

The rock wall was the biggest challenge, and was finished first. The floor of the cut and towpath, both partly flooded, came next, and layers of rubble were scattered pretty much everywhere. A few variations of the Dibble crane were included as placeholders (more will be added later). Thick, turbulent clouds convey an ominous mood (and help scatter the light into the shadows). A plume of dense smoke from blasting can be seen in the distance.

Despite some natural relief provided by the edges of the forest on either side, the picture so far has a dark, gritty look that seems appropriate.