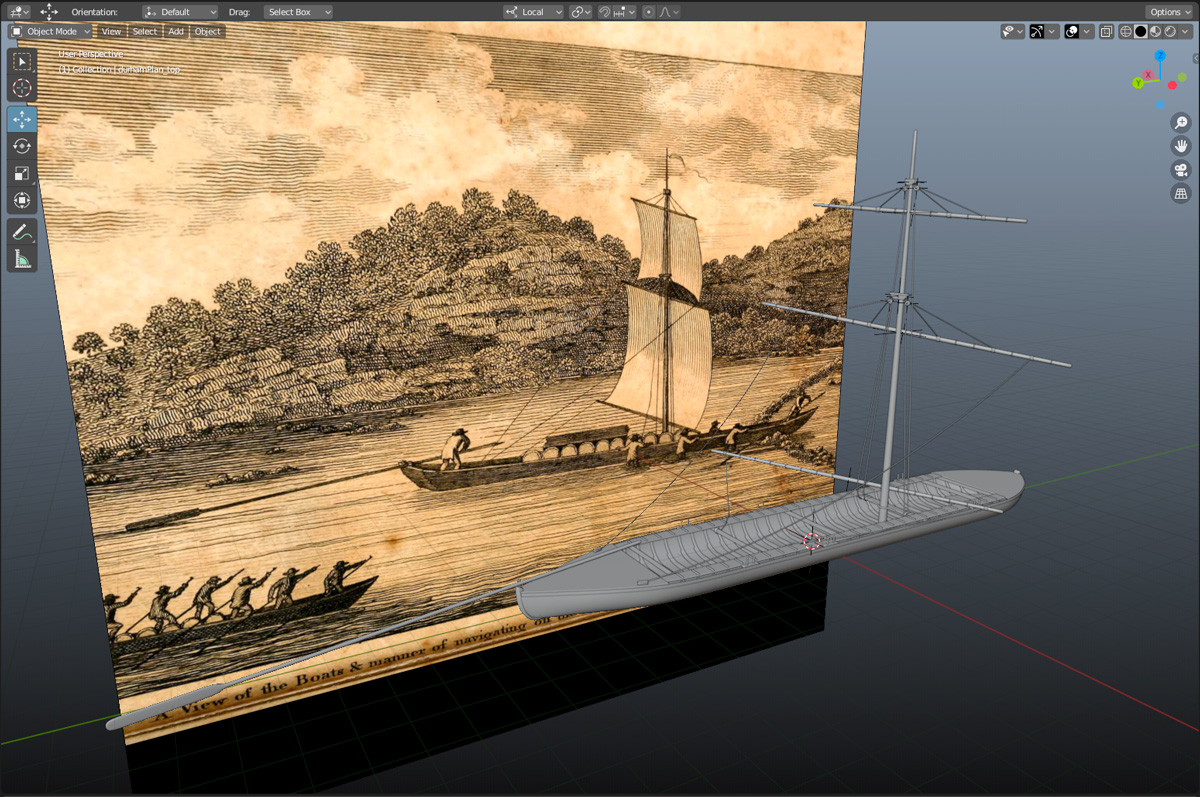

In her lively and informative introduction to the 1876 edition of The Pathfinder, Susan Fenimore Cooper describes (among many other things) her father’s ascent of the Mohawk Valley in 1808 en route to a naval posting in Oswego.

James Fenimore Cooper would have followed watercourses recently improved by the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company, taking advantage of locks and canals to bypass the Little Falls of the Mohawk River and to cross into Wood Creek. After pushing westward along this narrow channel for two days “they reached Oneida Lake, a broad sheet of dark-colored water . . . It was a day’s voyage, with the oars and poles, across the lake, against a head wind.”

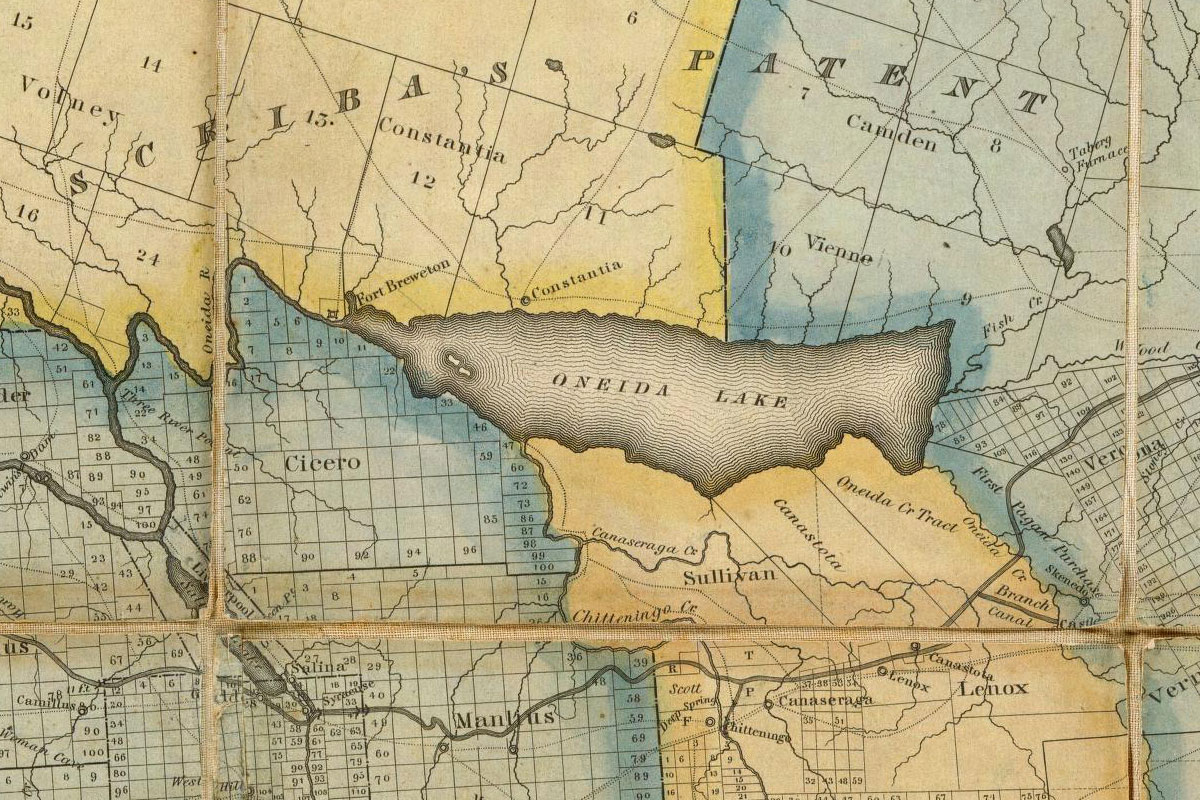

Oneida Lake was an important crossroads for early travelers on New York’s inland waterways. Voyagers crossing it could head east to the Hudson Valley, west to the Finger Lakes, or north to Lake Ontario. It was small, just 21 miles long and 5 miles wide, and shallow. Even so it could appear daunting to boat crews accustomed to navigating along narrow streams.

Lake Oneida’s east-west alignment exposed it to the full fury of storms arriving from the north and northwest, and its normally placid surface could, in a matter of moments, be churned into a deadly maelstrom of four- to six-foot waves.

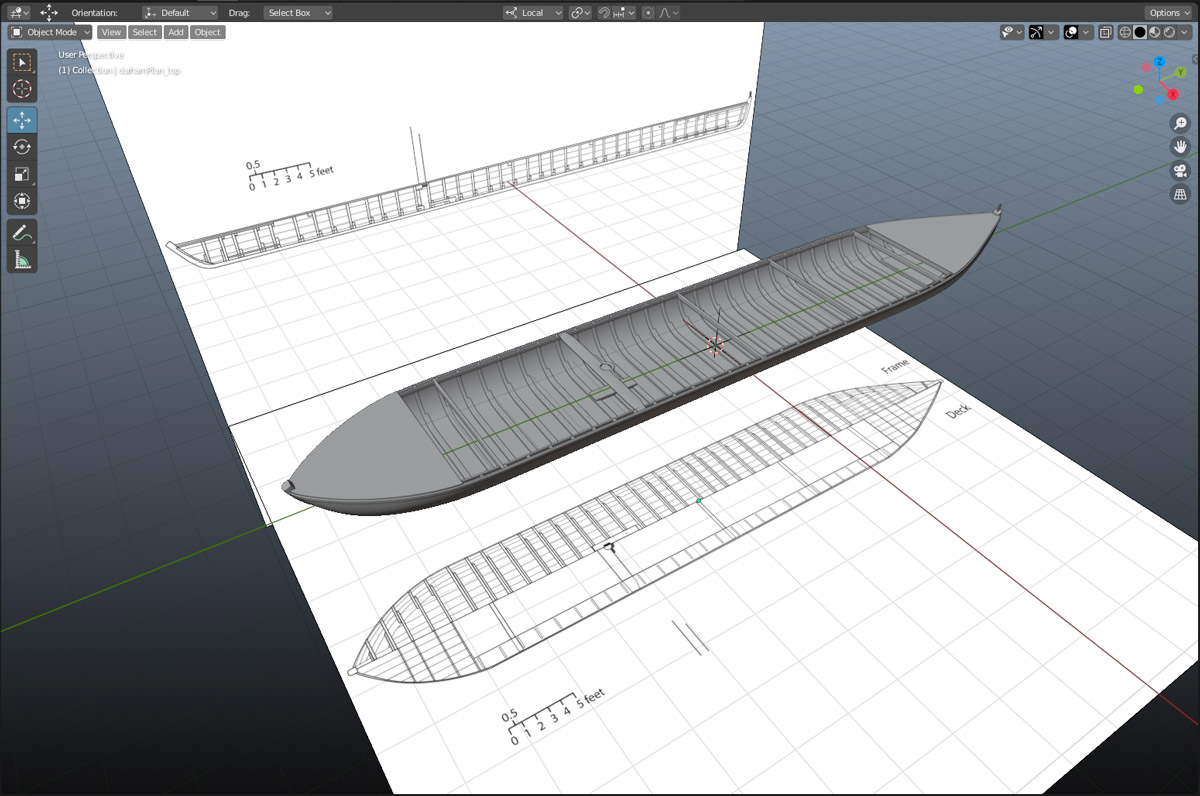

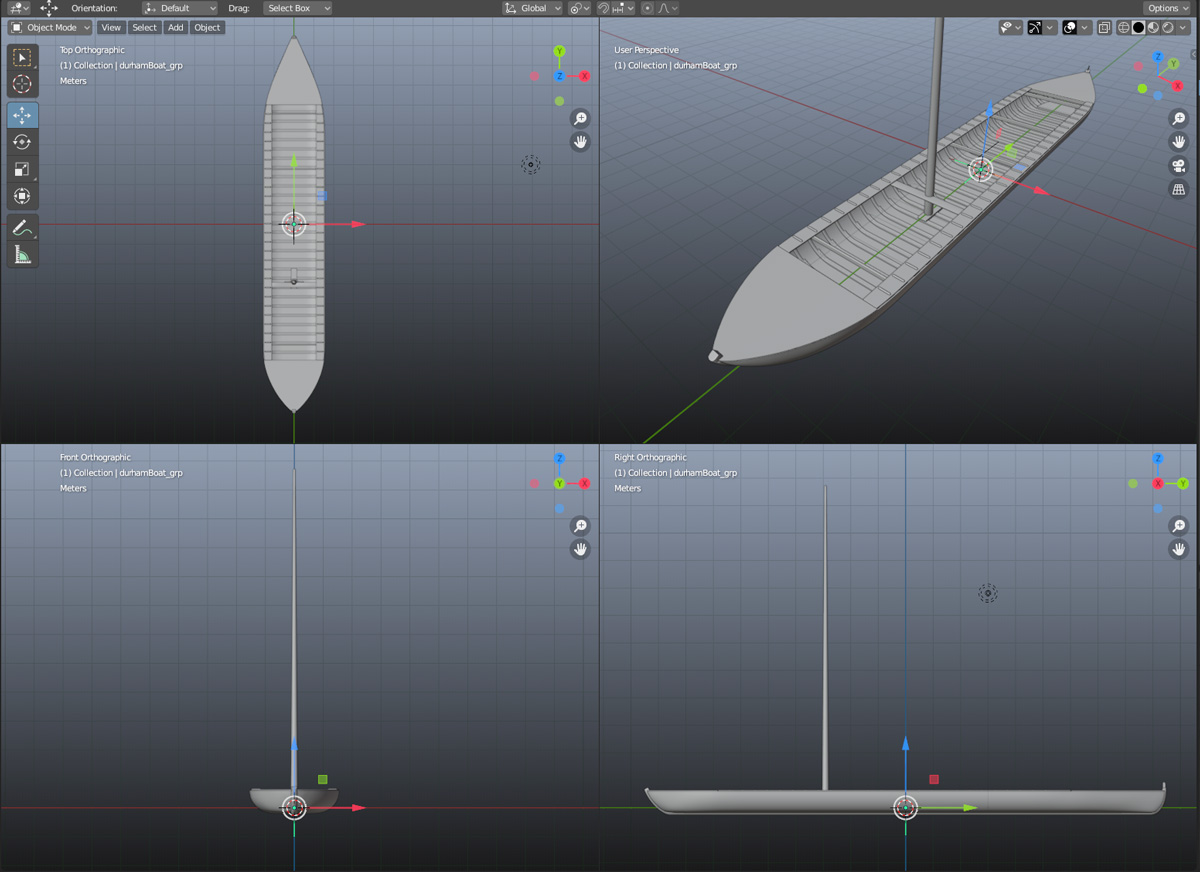

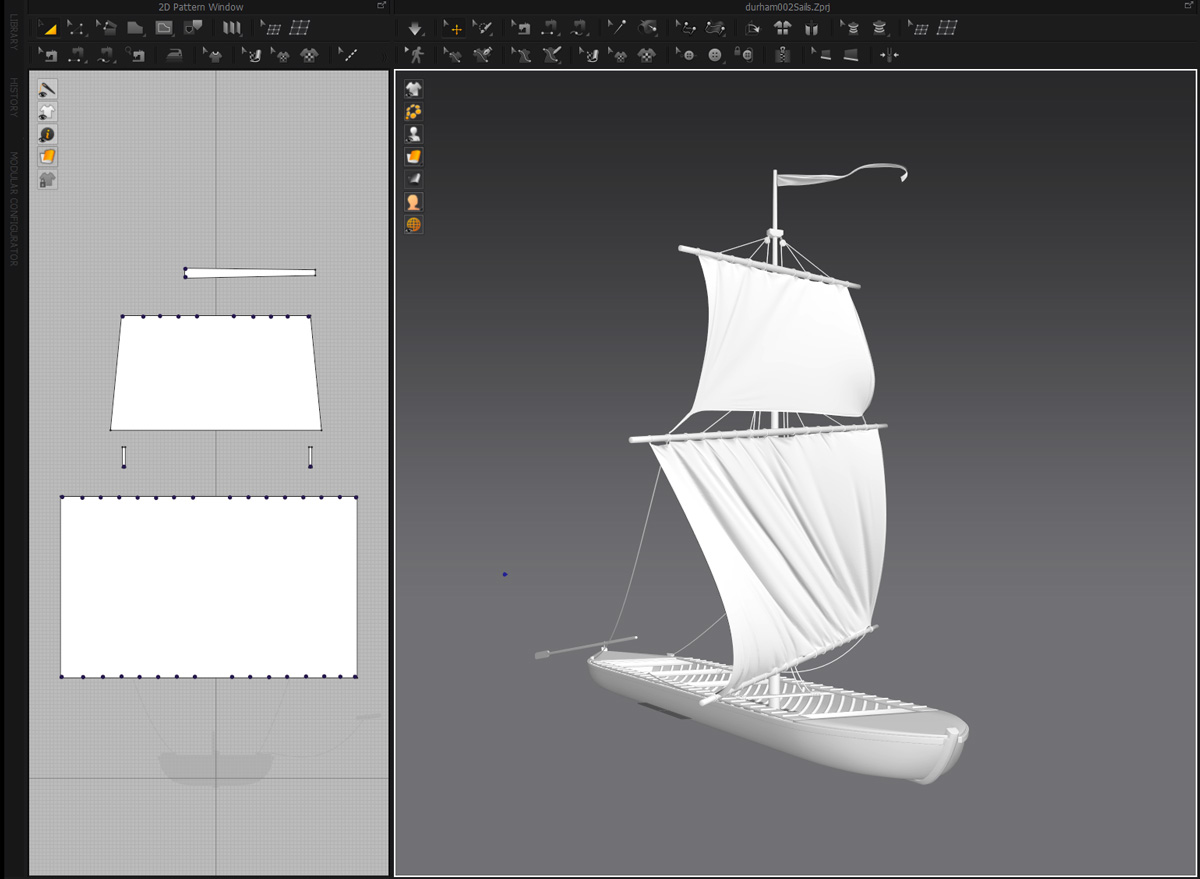

When that happened, the very features that made Durham boats so practical for river navigation – narrow beam, flat bottom, no keel, square rig – could quickly become liabilities. Hence most boats traveling east or west hugged the northern edge of the lake, where the heavily wooded lee shore offered some protection.

But the crew of the Durham boat discovered on the bottom of Oneida Lake, it seems, had set off on a different course.

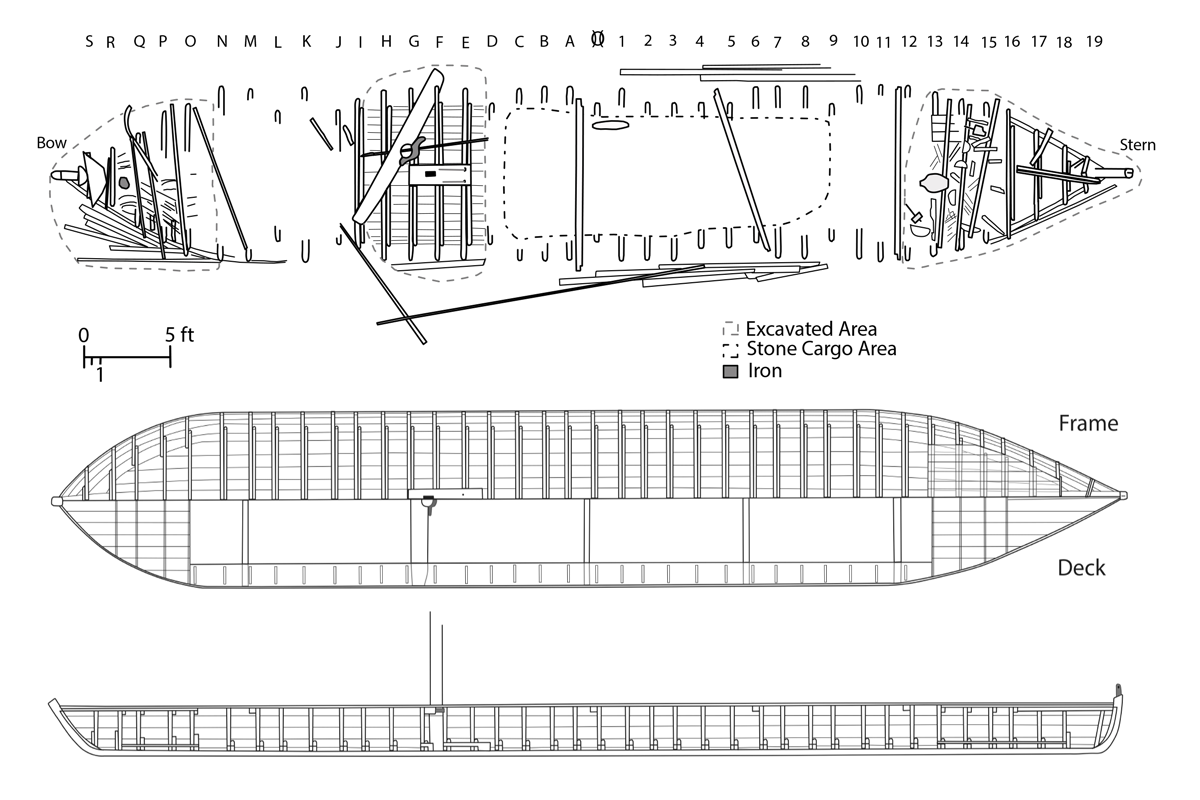

Along with the remains of the boat, the underwater archeology team uncovered its cargo, more than five tons of silty dolostone rock.

Dolostone is also known as dolomite and, as you might recall, it forms the Mountain Ridge west of Lockport. It occurs in various forms in a broad swath across New York state, and there is an outcropping of silty dolostone just south of Oneida Lake.

Members of the team suggest that the crew loaded their boat with the dolostone and planned to transport it to the north shore. As they wrote in their paper, Durham Boat – Defining a Vernacular Watercraft Type: “Attempting to sail across the short dimension of the lake would explain why the boat sank in the middle of the lake, when staying closer to the shore would have been safer.”

“Wherever the destination,” they continue, “the crew made it to the center of the lake before the vessel sank. . . . If the vessel was sunk in a storm, it is unclear why the captain risked his life for the relatively worthless cargo found on the site. It may have been that the light load and increasing breeze led him to believe that he could beat the storm across the lake. Whatever the circumstances, it would seem that the captain misjudged Oneida Lake, his boat, his skills, or some combination of these factors.”

No mention of the boat has been found in contemporary sources, and none of the artifacts found on the site can be precisely dated. The boat could have been lost, the team writes, any time between 1803 and 1840.

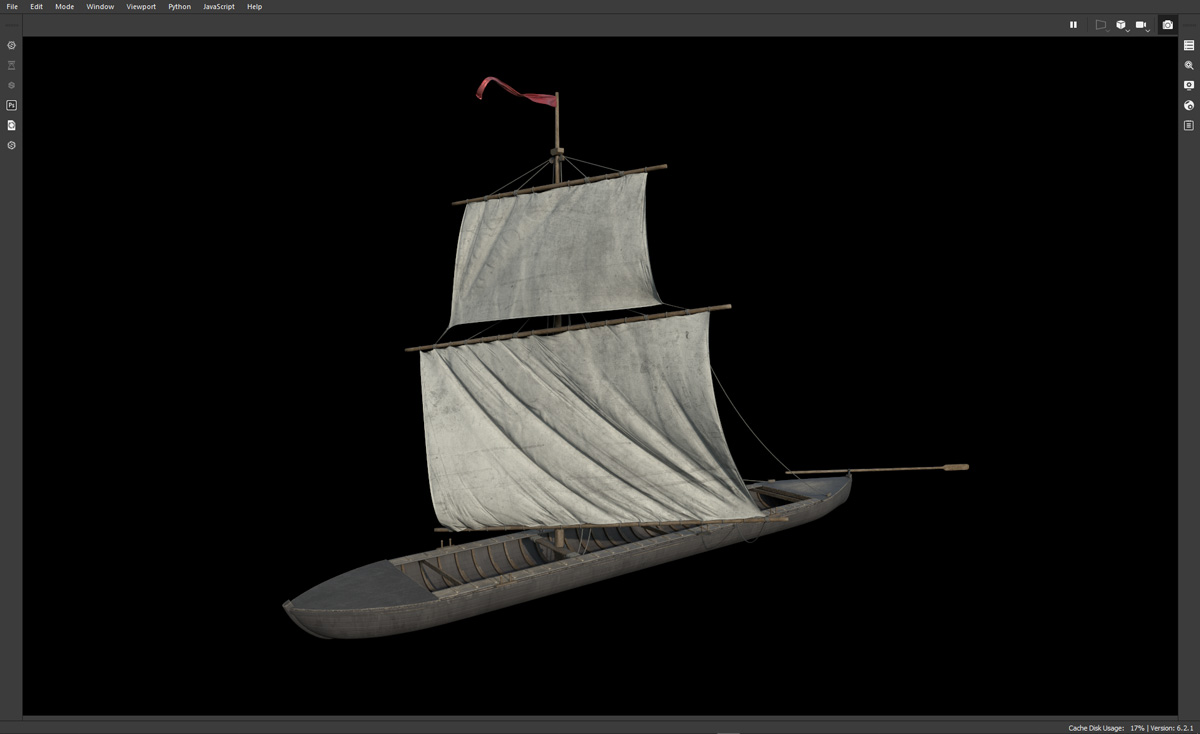

To depict the last crossing of the Oneida Lake Durham boat, I’ve chosen a date in the middle, September 1821.

There is some educated guesswork in this scene: Not only the date and situation, but also the method the crew might have used in their effort to beat the storm. Instead of rigging the square and topsail, they may have opted to leave them stowed and row across the lake. And the boat has been given the usual Durham complement of five, a steersman and four crew, though perhaps there were fewer on board when it foundered.

Their fate is anyone’s guess. The watercraft, loaded with rocks, would have gone straight to the bottom, but pieces of it may have been left behind on the surface. (Mast, spars and possibly the walking boards are missing from the excavation site.) The shore would have been in sight; perhaps some members of the crew, clinging to bits of flotsam, made it to safety.

September 1821 also falls in the middle of the Erie Canal construction period. By then the canal in this section, which bypassed Oneida Lake to the south, had been finished. The temperamental lake’s role in western navigation – along with the Durham boat – would soon come to an end.