The workers who excavated the Erie Canal used primitive tools: picks, shovels, and bars – long crowbars used to pry loose layers of rock. A laborer from the Middle Ages or even ancient Rome would not have felt much out of place in the Deep Cut in 1824.

They would have noticed one change, however, which was the use of black powder to blast through the solid rock. Black powder had been used for mining since the early 17th century. However, blasting – or “blowing,” as it was commonly called then – was haphazard and extremely dangerous despite nearly two hundred years of practical experience.

Many Erie Canal contractor receipts preserved in the New York State Archives include entries for powder, which would have been purchased from nearby wholesalers in 12 ½ or 25-pound kegs. “To 9 cages [kegs] of Powder for blasting out Lock bottomes on Erie Canal at four dollars and fifty cents per Cag,” reads one dated May 22, 1824, while another enumerates “116 Kegs Powder of Hubbard and Parsons at $4.50 pr k.” Along with labor and whiskey, it seems, powder was one of the contractor’s most significant expenses.

The powder used at Lockport was manufactured by Éleuthère Irénée du Pont at his gunpowder mill near Wilmington, Delaware, and was formulated specifically for blasting rocks.

Black powder was used because the excavation of the Deep Cut preceded the invention of dynamite. It also preceded (by many decades) the invention of pneumatic power drills. Instead, a forged steel drill was held in place by one man while another pounded it with a sledgehammer, rotating it a quarter turn between each blow. If this sounds tedious, it was – as well as dangerous for the fellow holding the drill, who risked getting his arm smashed if the hammer missed its mark. Probably not an uncommon occurrence given the amount of whiskey the workers would have consumed in any given day.

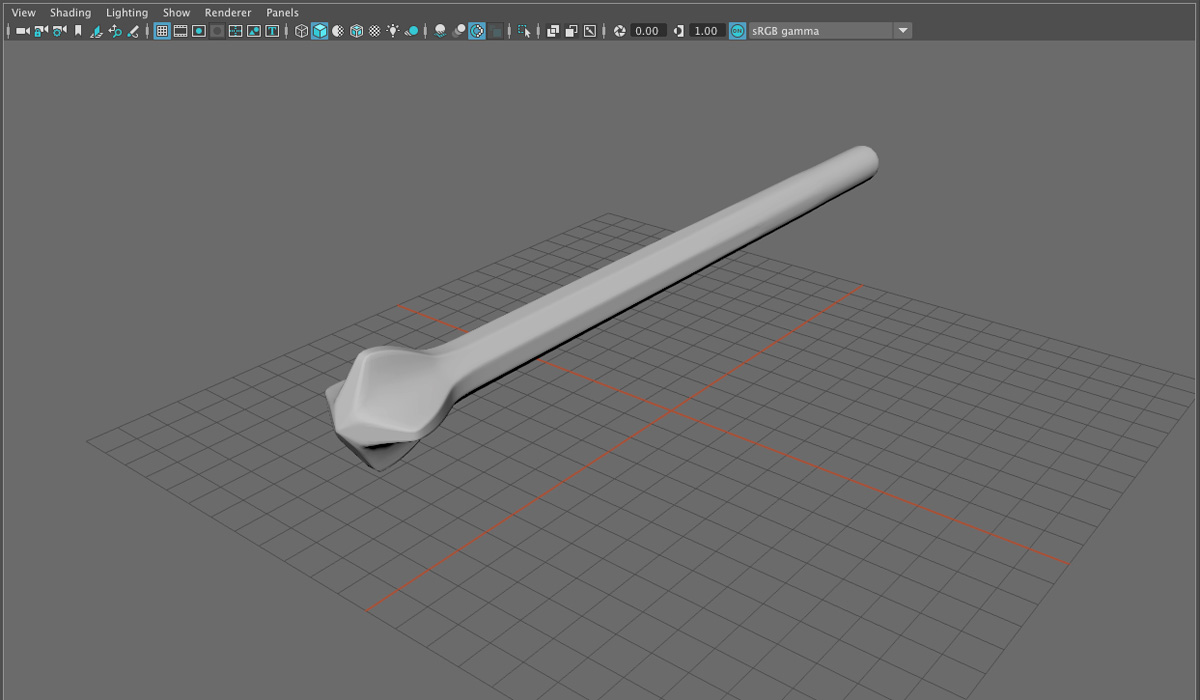

Legend has it that workers were stymied by the hard rock of the Deep Cut, which blunted their drills, until a local blacksmith named Botsford stepped forward with an improved process for forging hardened steel. His drills, which featured a diamond-shaped tip, enabled the work to go forward.

I haven’t been able to confirm this account. It appears in newspaper columns and several popular histories, but none cites a source. Botsford, who never seems to possess a first name, is variously described as being from Niagara Falls, Buffalo, or Lockport. But he is mentioned in none of the primary documents that I’ve checked, and there are no patents attributed to him. So either the story’s details have been lost to history or, at some point, it was simply made up.

Or maybe not. The Erie Canal Discovery Center in Lockport has a Botsford drill in its collection. Its provenance has never been documented, but it fits the historical description. Even if it isn’t actually from the period, it most likely is similar to the drills that would have been used. The drill model I’ve made is based on it.

The drills would have been used to create holes about two feet deep in which a quantity of powder would have been placed and fused. The process was carried out by “blowers” – often inexperienced and untrained workers. As part of the masculine culture of the canal workforce, these men took pride in exposing themselves to danger and (it’s worth noting again) consumed large quantities of whiskey on the job. It was an unfortunate combination, and the result was entirely predictable.

Many years later “Aunt Edna” Smith, one of the original inhabitants of Lockport, recorded her memories in the “Recollections of an Early Settler,” which was published in five parts in the Lockport Daily Union. In one installment she described the process of blowing rock:

“Many accidents occurred from the carelessness of the man in the use of powder, such as staying too near the blast at the time of the explosion, &c. If the fuse went out or burned slowly, they would rush back recklessly, to see what was the matter, often blowing them to revive the dying fire. Many a poor fellow was blown into fragments in this way. On some days the list of killed and wounded would be almost like that of a battle field.”

And the hazard wasn’t confined to workers:

“The blasting of the rocks for the foundation of the Locks, and the canal above, was a constant source of danger and annoyance to the inhabitants.

“Stones several inches in diameter were daily thrown over into Main street. When the warning cry of “Look Out!” was sounded for a blast, every one within range flew to a place of shelter. The small stones would rattle down like hail, and were anything but pleasant, particularly when one was caught with uncovered head. One stone weighing eighteen pounds was thrown over our house, and buried itself in the front yard.”

As historian Patrick McGreevy points out in Stairway to Empire: Lockport, the Erie Canal, and the Shaping of America, “Mrs. Smith’s home was more than seven hundred feet east of the Deep Cut.”

The shovel model for the scene is based on a shovel on display at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse, New York. The museum’s example dates from the 1830s and is clearly a frontier artifact, with a composite blade made from hardwood and forged iron. It’s not easy to imagine someone laboring 12 to 14 hours a day, excavating hard soil and broken rock, with this primitive tool.

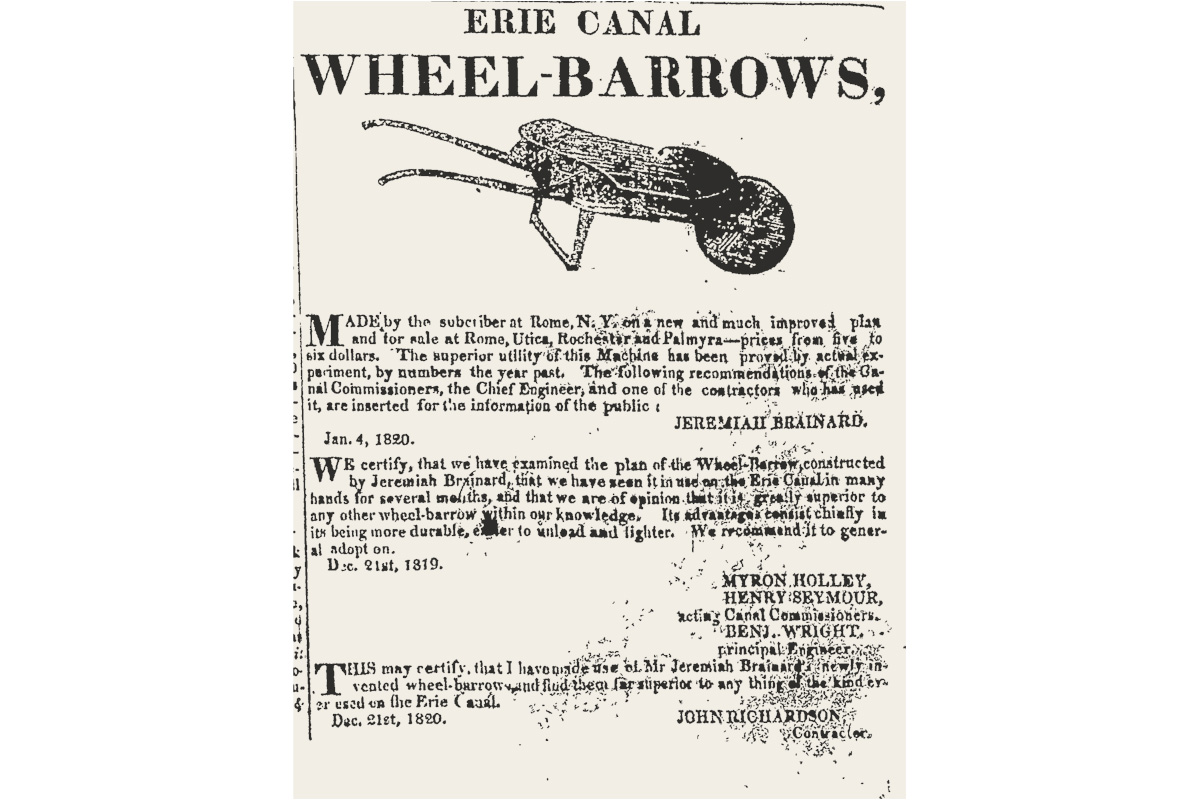

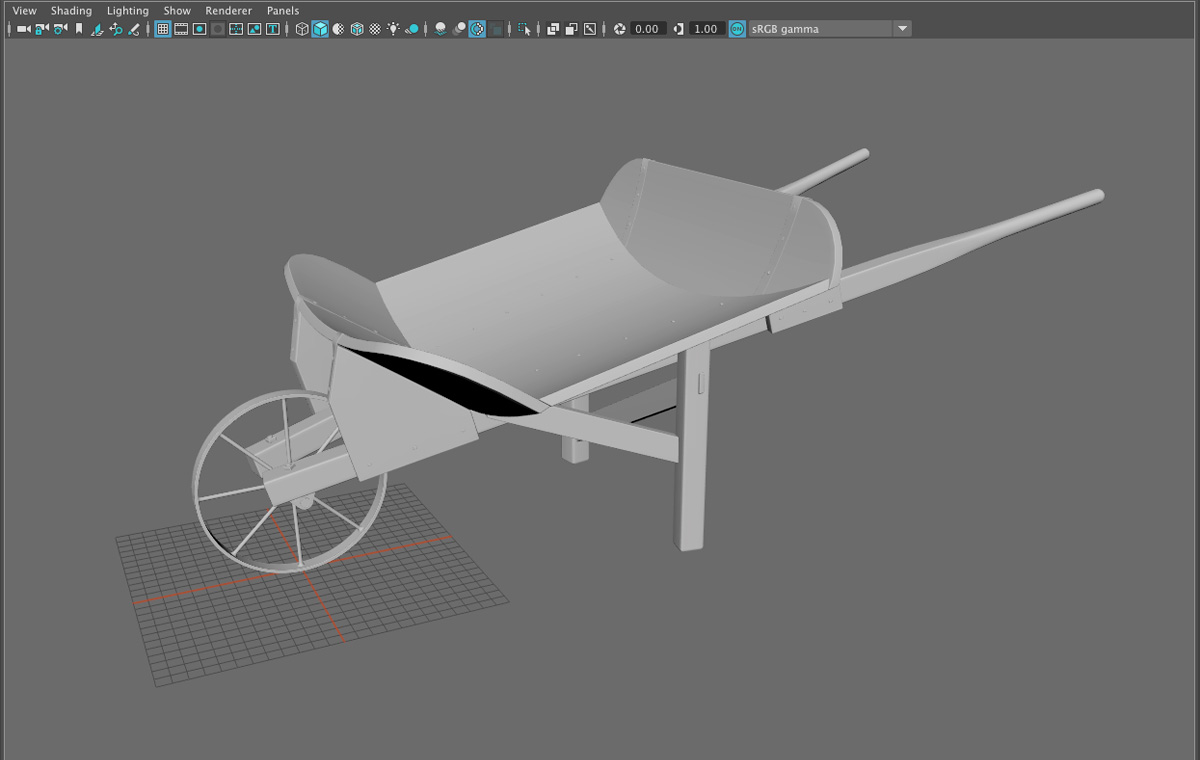

Workers at the Deep Cut and elsewhere on the canal would have hauled excavated rock and soil with the Brainard wheelbarrow, a revolutionary new design patented in 1819. The wheelbarrow, which used curved planks of wood for the tray, was significant enough to warrant a mention in the canal commissioners’ 1820 annual report: “Mr. Jeremiah Brainard of Rome, has invented a wheel barrow, which, without being more expensive than those in common use, is acknowledged by all who have seen it to be greatly superior to them. Its advantages consist in its being lighter, more durable, and much easier to unload.”

My wheelbarrow model is based on a surviving example from the 1830s on display at the Erie Canal Park museum in Camillus, New York.