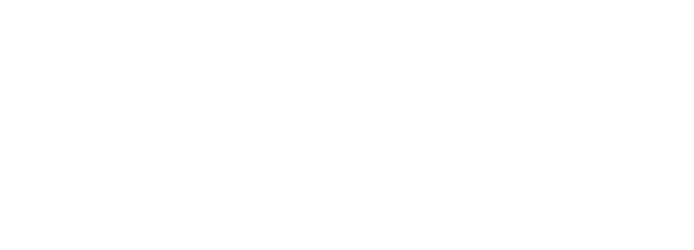

Long before European incomers began pushing their way up the Hudson and then west, the interior of what is now New York state had been settled by a Confederacy of five indigenous nations — the Haudenosaunee or People of the Longhouse. From east to west, these were the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca.

The French called them the Iroquois.

Their territory, embracing the Finger Lakes region of modern central and western New York, was covered with forests teeming with wildlife. Hunting, fishing, and agriculture sustained by the rich alluvial soil of the river valleys provided sustenance. The Confederacy provided protection.

The Confederacy was “the most powerful and sophisticated Indian nation north of the Aztecs,” notes Woodward A. Wickham, writing for the Institute of Current World Affairs in 1973. He continues:

“Besides securing domestic peace among the Five Nations, the Iroquois eventually dominated all other Indian states from the St. Lawrence River to the Tennessee, and from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi. The Confederacy homeland included the major east-west trail (now the New York Thruway), the eastern Great Lakes, and the headwaters of all four major river systems: the Delaware, Susquehanna, Ohio, and St. Lawrence. When Europeans settled the Atlantic coast, the Iroquois controlled all communication between them and the western tribes. The Iroquois of the Confederacy were the first Indians to acquire guns without being eradicated in the process, and soon grew rich through trade, raiding, and selling protection to Europeans and tributary Indians.”

In 1722 the Tuscarora, an Iroquois-speaking people who had fled their Carolina homeland to escape white incursion and warfare, were accepted into what now became the Six Nations. By then the Confederacy had endured for three centuries.

But the Haudenosaunee could not prevent European settlement around their perimeter. Caught between the British to the east and the French to the north and west, they were forced to choose sides. Their alliance with the British Crown worked to their benefit during the imperial wars of the 17th and early 18th centuries. But it proved disastrous once the colonies declared their independence.

The Confederacy itself was broken. The Oneidas and Tuscaroras joined the rebellious colonies and turned against their brethren to the west.

Scorched earth

For the Senecas the war all but ended in 1779, when George Washington finally turned his attention to the brutal conflict that had sputtered and raged for years along the New York and Pennsylvania frontier. The escalating cycle of atrocities and reprisals carried out between the Senecas and their Loyalist allies and the white settlers of the region could no longer be ignored. Washington’s response was to send an expeditionary force into the heart of the Seneca’s country. The invaders were to conduct a scorched-earth campaign and show their enemies no mercy.

“Sir,” wrote Washington to Major General John Sullivan on May 31. “The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the six nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.”

The Sullivan Expedition was one of the largest independent Continental operations of the war. That August a force of about 3,200 regulars and militia marched into Confederacy territory. The Senecas, along with their native and Loyalist allies, lost a single engagement at Newtown (present-day Elmira) and then retreated, unable to offer an effective defense. Following Washington’s orders, Sullivan’s force moved into the Genesee country, systematically destroying villages, burning fields, and slaughtering livestock.

When the campaign ended the native survivors sought refuge near the British forts along the Niagara frontier. That winter their numbers were further depleted by sickness and starvation.

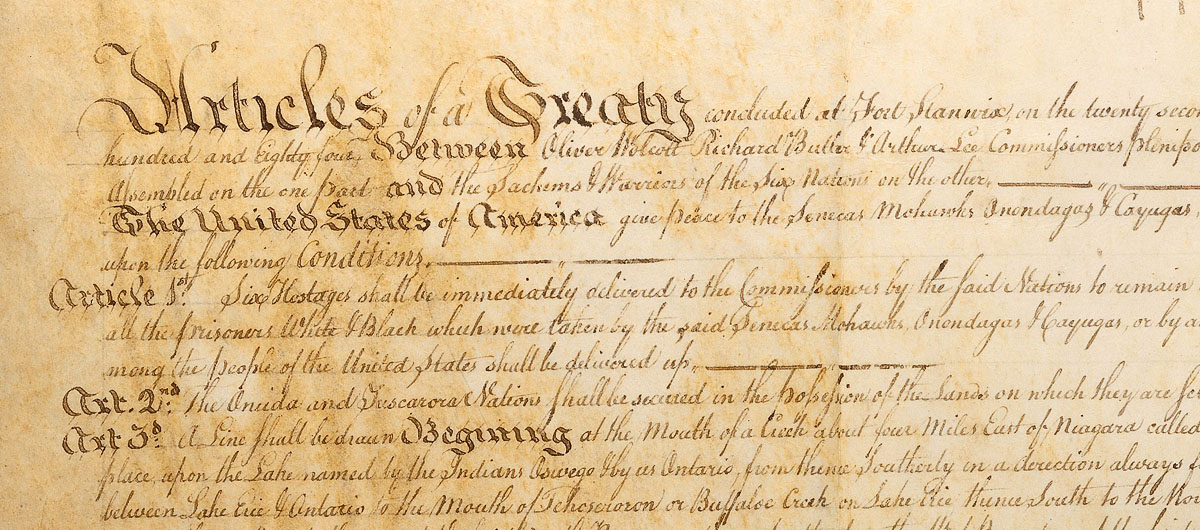

In 1781 the fate of the Six Nations was sealed by the Continental and French victory at far-away Yorktown, Virginia. In signing the Treaty of Paris two years later the British ceded much of their North American empire to their former colonies. The treaty made no mention of the Haudenosaunee, some of whom made their way to join the British in Canada. Those who remained on the United States side of the new border were simply abandoned.

One of the prime causes of the American Revolution had been hunger for western land. British colonial policy had barred settlement beyond the Appalachians. Now the door was flung wide open. Thousands of veterans who had participated in the Sullivan campaign had returned to New England and elsewhere and were spreading word of the fertile country of the Genesee. There for the taking.

Interlocking forces

In his book Conspiracy of Interests: Iroquois Dispossession and the Rise of New York State historian Lawrence M. Hauptman defines three “interlocking forces . . . that helped create an urban industrial corridor in the heart of Iroquoia”: land, transportation, and national defense.

Of these, transportation meant roads, of course, but also canals: first, the waterway improvements of the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company; later, the much larger and more disruptive Grand Canal that would connect the Hudson River to Lake Erie.

Many of the men who populate the histories of these canals — including Philip Schuyler, Peter B. Porter, and DeWitt Clinton — were unscrupulous in their dealings with the Six Nations. In their eyes the Senecas and their allies were broken enemies that could be swept aside in the rush to open western New York to white settlement.

They applied the same policy to their nominal allies, the Oneidas, whose territory lay across a natural east-west communications corridor and included the Great Carrying Place, the strategic portage that connected the headwaters of the Mohawk River with Wood Creek and, in turn, the Atlantic coast to the Great Lakes.

State politicians and speculators (who were often one and the same) ignored the weak federal government and its laws regulating trade and land sales between settlers and native peoples and set about depriving the Oneidas of their home. The ink had hardly dried on their illegal “treaties” before the surveyors arrived and workers for the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company began clearing Wood Creek.

On Lake Erie, state and private actors chipped away at the large Seneca reservation at Buffalo Creek — which had also become a home for native refugees from across the Confederacy — clearing the way for the western terminus of the Erie Canal and the future growth of the city of Buffalo.

By the 1820s the people of the Six Nations would be boxed into reservations scattered around New York state, having fought an increasingly hopeless rear-guard action against a powerful array of private and state interests. They had been outnumbered, riven by internal divisions, and betrayed by the very missionaries and agents who ostensibly had been sent to protect them. Vast tracts of forest, lakes, and river bottomland had been surrendered for a pittance.

But they were not entirely defeated. Unlike the indigenous peoples of the southern United States, the people of the Six Nations successfully resisted removal. There would be no northern counterpart to the Trail of Tears. Only the Oneida Nation — which split in two with the larger part moving to Wisconsin and later Ontario, Canada — would consider abandoning their homeland. The rest remained.

But they had been pushed out of the way of the Erie Canal.