The balance of power between Rochester and the Genesee River would finally begin to shift after 1865.

The river was becoming an increasingly unruly neighbor. Freshets in 1817 and 1819 swept away buildings and damaged mills and millraces. Another in 1835, described by Rochester chronicler Henry O’Reilly as “the greatest flood ever known in the Genesee River,” undermined the west abutment of the second Main Street bridge. The bridge’s successor was carried off by another flood in 1857.1

Observers blamed human activity — clearcutting forests and draining wetlands, and construction of bridges, levees, and other obstructions — and warned that it would only get worse. But no one was prepared for the flood of 1865.

That March the river, swollen by an early spring thaw, roiled through the city. It inundated the new Main Street bridge, undermined buildings on both banks, and nearly crested the parapets of the second aqueduct, 27 feet above the riverbed. It was the most destructive flood in the city’s history, causing an estimated one million dollars in damage.2 In response, a commission was appointed by the state to investigate its causes and to recommend measures to prevent it from happening again.

Their report, published the following year, included a list of seven commonsense remedies that included dismantling obstructions, erecting movable dams, and building retaining walls. But in a supplemental report, Isaac F. Quinby, a mathematics professor at the University of Rochester who had assisted with the committee’s investigations, urged the city to take more drastic action: “To blast out a channel along the axis of the river from High Falls to a point about half way between Main street bridge and the aqueduct, or still better, to a point above the latter structure.” The channel would be seventy feet wide at the top and fifty feet wide at the bottom. Its average depth would be ten feet. Excavating it would be expensive, Quinby warned: An estimated 54,222 cubic yards of rock would need to be removed and 2,926 cubic yards of masonry retaining walls built, all at a cost of $121,611. But if it could be accomplished, his plan would increase the river’s capacity and might spare the city from future inundations.3

But Quinby’s plan was shelved, and for the next several decades the local government did almost nothing to protect the city from high water. The floods became more frequent. From the end of the Civil War to the turn of the century the Genesee inundated nearby neighborhoods nine times. In March 1902 a flood nearly as destructive as the one of 1865 swept through downtown; it was followed by another in July — incredibly, during the high summer season. In February 1904 the river, choked with ice, struck again.4

In 1905 another commission was appointed and another report compiled. Of the seven flood control recommendations made in 1866, the new commissioners noted, only three had been completed and another “partly accomplished.”5 But their report went nowhere; nothing more was done.

The flood of March 1913 would be the wakeup call.

The weather system that created it extended from the lower Ohio Valley to western New York. Over several days a series of storms funneled along a low-pressure trough delivered high winds, tornadoes, hail, and sleet throughout the Midwest and South. Up to nine inches of rain fell on Indiana, Ohio, and northwestern Pennsylvania. Rising water trapped thousands of people; newspapers reported that up to two hundred died in Dayton, Ohio, when fire broke out within the submerged part of the city.6

The Great Flood of 1913 remains one of the most widespread natural disasters in the history of the United States. Newspaper editors, running out of ways to describe the devastation, compared it to the Johnstown Flood of 1889 and the Great Galveston Storm of 1900. Recent estimates of the number of people killed range from 650 to more than 900.7

The record rainfall and resulting runoff flooded communities and interrupted train schedules throughout western New York. In Rochester, on the edge of the storm system, the Genesee River overflowed its banks and filled nearby basements and streets with water. But there were no fatalities.

A local newspaper quoted a visiting “Pittsburgh engineer” who, when asked how such events might be averted in the future, recommended straight away that “the river bottom ought to be blasted out from Court Street to the Upper Falls.”8

The Common Council at last was roused to take action. It may have been stung by criticism from local merchants, including the Front Street clothing salesman who posted signs in the windows of his flooded store that read: “Water in here Friday 10 p.m., 4 feet. Damage probably $3,500. Why didn’t the city build retaining walls along the river instead of one-half million Exposition Park?”9 Or perhaps council members looked to Dayton and realized that next time Rochester might not be so lucky.

I. F. Quinby’s nearly fifty-year-old plan was dusted off and that December — nine months after the floodwaters receded — the council approved a contract to deepen the riverbed.10

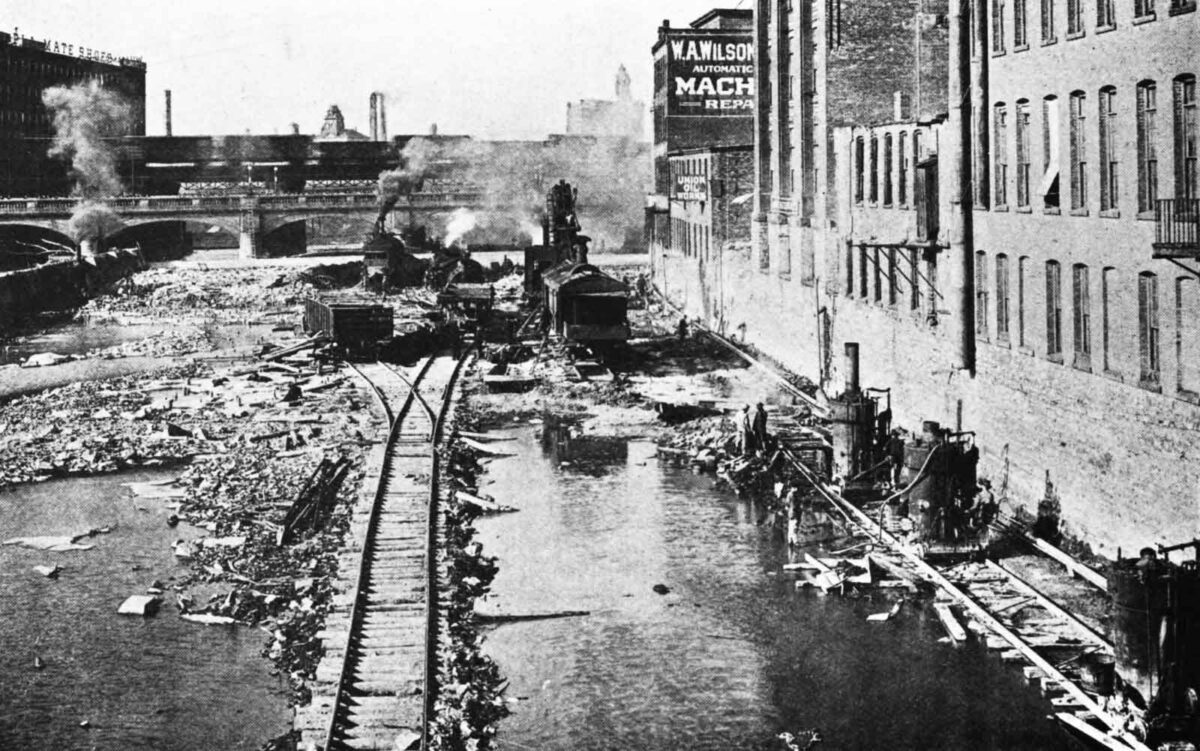

By now the scale of the project had changed dramatically. The excavation would extend from bank to bank, an average width of 240 feet, from just above Court Street to the brink of the High Falls, a distance of 2,700 feet.11

Contractors constructed a dam down the center of the river so it could be diverted first to one side, then the other, exposing the rocky bed.12 For more than five long years city residents endured the constant din of drilling and blasting and the incessant hammering of steam-powered channeling machines. By the spring of 1919, when the last contract was completed, more than 150,000 cubic yards of rock and earth had been removed — nearly three times Quinby’s 1866 estimate — and the project’s cost had soared to nearly a million dollars.13

The final depth of the excavation is not easy to pin down. The original ordinances specified that the riverbed would be lowered an average of five feet from above the aqueduct to the brink of the High Falls.14 Estimates based on the geology of the riverbed and gorge indicate that the High Falls themselves were lowered about ten feet.15

Within a few years the Court Street Dam would be built in downtown Rochester as part of the new Barge Canal system, which would replace the old Erie Canal and also provide a measure of flood control. The final touch would be added in 1952 with the completion of the Mount Morris Dam, thirty miles south of Rochester. This 230-foot-high dry gravity dam serves as the ultimate backstop, impounding high water during extreme weather events to reduce flooding and protect property from Mount Morris to Lake Ontario.

The Genesee River had finally been tamed, and in the process its historic appearance was permanently changed. This was especially true in downtown Rochester where, for all practical purposes, the river’s channel was by now completely man-made.

To help you imagine the extent of these changes, just pretend for a moment that you are accompanying Nathaniel Rochester, William Fitzhugh, and Charles Carroll on their first visit to the Falls of the Genesee. Emerging from the dense forest on the east bank, you are greeted by a landscape much like the one shown here.

The last shelf of the falls reaches across the river to the opposite bank, which rises gradually to the foot of a low, stony ledge. This nondescript feature, which eventually will be buried beneath the city of Rochester, will play a role in the development of the village along with its vibrant flour-milling industry and, eventually, the construction of the Rochester aqueduct.

The year is 1804. Soon a stream of incoming settlers, tentative at first and then becoming more steady, will start the long process of transforming the landscape and river.

- Henry O’Reilly, Settlement of the West: Sketches of Rochester; with Incidental Notices of Western New-York (Rochester, New York: William Alling, 1838), 351. Dorothy S. Truesdale, “Historic Main Street Bridge,” Rochester History 3 (April 1941), 12. Report of the Committee on Investigation of Flood Conditions Affecting the City of Rochester, N. Y. (Rochester, New York: W. W. Morrison, 1905), 8; image copy, HathiTrust (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b77585 : accessed 29 November 2024) > image 20. ↩︎

- Annual Report of the State Engineer and Surveyor of the State of New York for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1896 (Albany: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford, 1897), 33; image copy, HathiTrust (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015067178494 : accessed 29 November 2024) > image 53. ↩︎

- Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, 96th session (Albany: G. Wendell, 1866), doc. no. 117, “Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Investigate the Causes of the Inundation of the City of Rochester in March, 1865,” p. 23–24; image copy, HathiTrust (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924093488496: accessed 29 November 2024) > images 1141–1142. ↩︎

- Report of the Committee on Investigation of Flood Conditions Affecting the City of Rochester, N. Y. (Rochester, New York: W. W. Morrison. 1905), table, 45–46; image copy, HathiTrust (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b77585 : accessed 29 November 2024) > images 75–76. ↩︎

- Ibid., 70–71; image copy, HathiTrust (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b77585 : accessed 29 November 2024) > images 100–101. ↩︎

- “Hotel and 200 People Burned,” The (Rochester, New York) Democrat and Chronicle, 27 March 1913, p. 2, col. 2; image copy, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/image/135734903 : accessed 29 November 2024). ↩︎

- “Great Flood of 1913,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Flood_of_1913 : accessed 29 November 2024). ↩︎

- “After Attack on City River Gives Ground,” The (Rochester, New York) Democrat and Chronicle, 30 March 1913, p. 27, col. 1; image copy, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/image/135734990 : accessed 29 November 2024). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Final Ordinance 4379: Construction of Movable Dams and Deepening Genesee River Bed,” Proceedings of the Common Council of the City of Rochester: 1913 (Rochester, New York: Rochester Herald Press, 1914), 612; image copy, Google Books (https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/YWkwAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 : accessed 29 November 2024). ↩︎

- “Genesee River Flood Protection for the Year 1916,” Annual Reports of the Department of Engineer of the City of Rochester for the Years 1914, 1915 and 1916 (Rochester, New York: John P. Smith, 1917), 5: image copy, Google Books (https://www.google.com/books/edition/Annual_Report/-uA2AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 : accessed 30 November 2024). ↩︎

- The foundation of this dam can still be seen during periods of low water. ↩︎

- “Deepening Genesee River for Flood Protection,” Annual Reports of the Department of Engineering of the City of Rochester: Years 1917, 1918, 1919 and 1920 (Rochester, New York: John P. Smith, 1921), 6; image copy, Google Books (https://www.google.com/books/edition/Annual_Report/Kd42AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 : accessed 29 November 2024). “H. W. Rippy Obtains Figures,” The (Rochester) Democrat and Chronicle, 1 November 1919, p. 15, col. 2; image copy, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/image/135411869 : accessed 29 November 2024). The newspaper reported that the city paid $839,781.49; adding $115,000 paid to cover a loss by the contractor brings the total to $954,781.49, or more than $16 million in today’s currency: “CPI Inflation Calculator,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm). ↩︎

- Report by the public works committee, Proceedings of the Common Council of the City of Rochester: 1913 (Rochester, New York: Rochester Herald Press, 1914), 611; image copy, Google Books (https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/YWkwAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 : accessed 29 November 2024). ↩︎

- Thomas X. Grasso, “Geology and History of the Rochester Gorge, Part One.” Rochester History 54 (Fall 1992), 21. ↩︎